By James Clayton

North America technology reporter

In March last year a video appeared to show President Volodymyr Zelensky telling the people of Ukraine to lay down their arms and surrender to Russia.

It was a pretty obvious deepfake – a type of fake video that uses artificial intelligence to swap faces or create a digital version of someone.

But as AI developments make deepfakes easier to produce, detecting them quickly has become all the more important.

Intel believes it has a solution, and it is all about blood in your face.

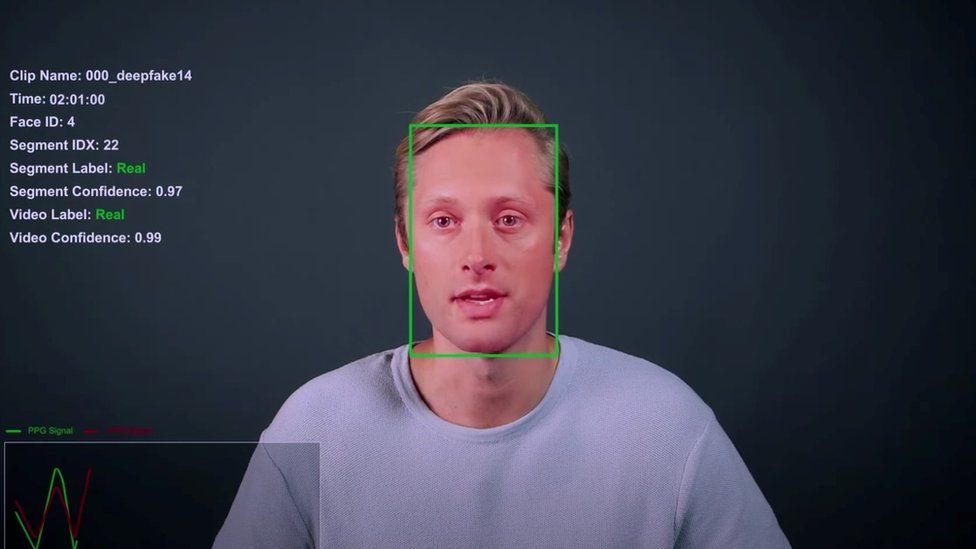

The company has named the system “FakeCatcher”.

In Intel’s plush, and mostly empty, offices in Silicon Valley we meet Ilke Demir, research scientist at Intel Labs, who explains how it works.

“We ask what is real about authentic videos? What is real about us? What is the watermark of being human?” she says.

Central to the system is technique called Photoplethysmography (PPG), which detects changes in blood flow.

Faces created by deepfakes don’t give out these signals, she says.

The system also analyses eye movement to check for authenticity.

“So normally, when humans look at a point, when I look at you, it’s as if I’m shooting rays from my eyes, to you. But for deepfakes, it’s like googly eyes, they are divergent,” she says.

By looking at both these traits, Intel believes it can work out the difference between a real video and a fake within seconds.

The company claims FakeCatcher is 96% accurate. So we asked to try out the system. Intel agreed.

We used a dozen or so clips of former US President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden.

Some were real, some were deepfakes created by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Watch: The BBC’s James Clayton puts a deepfake video detector to the test

In terms of finding the deepfakes, the system appeared to be pretty good.

We mostly chose lip-synced fakes – real videos where the mouth and voice had been altered.

And it got every answer right, bar one.

However when we got onto real, authentic videos it started to have a problem.

Several times the system said a video was fake, when it was in fact real.

The more pixelated a video, the harder it is to pick up blood flow.

The system also does not analyse audio. So some videos that seemed fairly obviously real by listening to the voice were allocated as fake.

The worry is that if the programme says a video is fake, when it’s genuine, it could cause real problems.

When we make this point to Ms Demir, she says that “verifying something as fake, versus ‘be careful, this may be fake’ is weighted differently”.

She is saying the system is being overly cautious. Better to catch all the fakes – and catch some real videos too – than miss fakes.

Deepfakes can be incredibly subtle: A two second clip in a political campaign advert, for example. They can also be of low quality. A fake can be made by only changing the voice.

In this respect, the ability for FaceCatcher to work “in the wild” – in real world contexts – has been questioned.

Image source, Intel

A collection of deepfakes

Matt Groh is an assistant professor at Northwestern University in Illinois, and a deepfakes expert.

“I don’t doubt the stats that they listed in their initial evaluation,” he says. “But what I do doubt is whether the stats are relevant to real world contexts.”

This is where it gets difficult to evaluate FakeCatcher’s tech.

Programmes like facial-recognition systems will often give extremely generous statistics for their accuracy.

However, when actually tested in the real world they can be less accurate.

Earlier this year the BBC tested Clearview AI’s facial recognition system, using our own pictures. Although the power of the tech was impressive, it was also clear that the more pixelated the picture, and the more side-on the the face in the photo was, the harder it was for the programme to successfully identify someone.

In essence, the accuracy is entirely dependent on the difficulty of the test.

Intel claims that FakeCatcher has gone through rigorous testing. This includes a “wild” test – in which the company has put together 140 fake videos – and their real counterparts.

In this test the system had a success rate of 91%, Intel says.

However, Matt Groh and other researchers want to see the system independently analysed. They do not think it’s good enough that Intel is setting a test for itself.

“I would love to evaluate these systems,” Mr Groh says.

“I think it’s really important when we’re designing audits and trying to understand how accurate something is in a real world context,” he says.

It is surprising how difficult it can be tell a fake and a real video apart – and this technology certainly has potential.

But from our limited tests, it has a way to go yet.