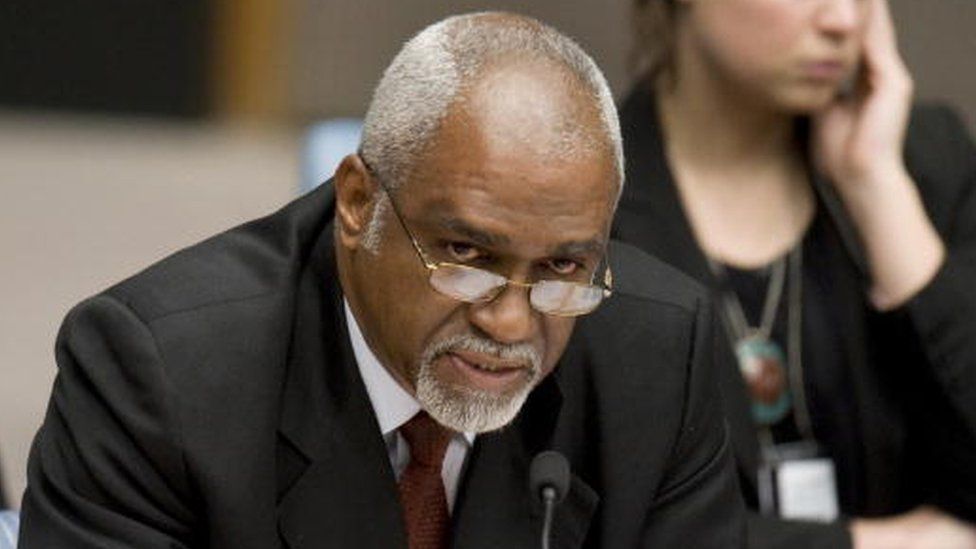

Patrick Robinson has been a member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2015

By Joshua Nevett

BBC Politics

A UN judge says the UK is likely to owe more than £18tn in reparations for its historic role in transatlantic slavery.

A report co-authored by the judge, Patrick Robinson, says the UK should pay $24tn (£18.8tn) for its slavery involvement in 14 countries.

But Mr Robinson said the sum was an “underestimation” of the damage caused by the slave trade.

He said he was amazed some countries responsible for slavery think they can “bury their heads in the sand”.

“Once a state has committed a wrongful act, it’s obliged to pay reparations,” said Mr Robinson, who presided over the trial of Slobodan Milosevic, the former Yugoslav president.

Mr Robinson spoke to the BBC ahead of his keynote speech at an event to mark Unesco’s Day for Remembering the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Abolition at London’s City Hall on Wednesday.

He’s been a member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2015 and has been researching reparations as part of his honorary presidency of the American Society of International Law.

He brought together a group of economists, lawyers and historians to produce the Brattle Group Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery.

The report, which was released in June, is seen as one of the most comprehensive attempts yet to put figures on the harms caused by slavery, and calculate the reparations due by each country.

In total, the reparations to be paid by 31 former slaveholding states – including Spain, the United States and France – amount to $107.8tn (£87.1tn), the report calculates.

The valuation is based on an assessment of five harms caused by slavery and the wealth accumulated by countries involved in the trade. The report sets out decades-long payment plans but says it is up to governments to negotiate what sums are paid and how.

In his speech at the London mayor’s office, Mr Robinson said reparations were “necessary for the completion of emancipation”.

He said the “high figures” in the Brattle Report “constitute a clear, unvarnished statement of the grossness” of slavery.

In his own speech, London Mayor Sadiq Khan said the transatlantic slave trade “remains the most degrading and prolonged act of human exploitation ever committed”.

“There should be no doubt or denial of the scale of Britain’s involvement in this depraved experiment,” Mr Khan said.

Limited success

The Brattle Report has generated interest within the reparations movement, but the governments implicated are highly unlikely to accept its recommendations.

Caribbean countries have sought slavery reparations from these governments for years with limited success.

Earlier this year, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak dismissed calls for the UK government to apologise and pay reparations for its role in slavery.

Rishi Sunak rejects MP’s call for slave trade apology

British authorities and the monarchy were participants in the trade, which saw millions of Africans enslaved and forced to work, especially on plantations in the Caribbean, between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Britain also had a key role in ending the trade through Parliament’s passage of a law to abolish slavery in 1833.

The British government has never formally apologised for slavery or offered to pay reparations.

When asked if he thought Mr Sunak would take the Brattle Report seriously, Mr Robinson said: “I certainly hope he will.”

Mr Robinson said he hoped Mr Sunak would change his opinion on reparations and urged him to read the Brattle Report.

But he added: “For me, it goes beyond what the government and the political parties want.

“Of course they should set the tone. But I would like to see the people of the United Kingdom involved in this exercise as a whole.”

When asked if the £18.8tn figure could be too little, Mr Robinson said: “You need to bear in mind that these high figures, as high as they appear to be, reflect an underestimation of the reality of the damage caused by transatlantic chattel slavery. That’s a comment that cannot be ignored.”

He said the sums in the report “accurately reflect the enormity of the damage cause by slavery”.

He said: “It amazes me that countries could think, in this day and age, when the consequences of that practice are clear for everyone to see, that they can bury their heads in the sand, and it doesn’t concern them. It’s as though they are in a kind of la la land.”

Legal debate

As to how reparations could be achieved, Mr Robinson said that was up the governments to decide.

“I believe a diplomatic solution recommends itself,” he said. “I don’t rule out a court approach as well.”

The legal status of reparations demands by states is highly contested.

Representatives of Caribbean states have previously stated their intention to bring the issue to the ICJ, but no action has been taken.

Reparations are broadly recognised as compensation given for something that was deemed wrong or unfair, and can take the many forms.

In recent years, Caribbean leaders, activists and the descendants of slave owners have been putting Western government under increasing pressure to engage with the reparations movement.

Some of the descendants of slave owners – such as former BBC journalist Laura Trevelyan, and the family of 19th Century Prime Minister William Gladstone – have attempted to make amends.

In response to the BBC’s request for comment, the UK government pointed to comments made by Foreign Minister David Rutley in Parliament earlier this year.

He said: “We acknowledge the role of British authorities in enabling the slave trade for many years before being the first global force to drive the end of the slave trade in the British empire.”

He said the government believes “the most effective way for the UK to respond to the cruelty of the past is to ensure that current and future generations do not forget what happened, that we address racism, and that we continue to work together to tackle today’s challenges”.