Dave used his pension to pay for an operation because he was in too much pain to wait for NHS treatment

By Alison Holt and Michelle Roberts

BBC News

Cost of living pressures and NHS backlogs are creating a two-tier health service in England, where people who cannot afford to pay wait longer for care, warns a watchdog.

The annual report by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) is likely to be its last stocktake of the health and social care system before a general election.

It makes for troubling reading, painting a picture of unfair provision.

The government says it is investing record sums to improve access to care.

The CQC, which inspects and regulates care providers, says local authority budgets have failed to keep pace with rising costs and the increase in the number of people needing care.

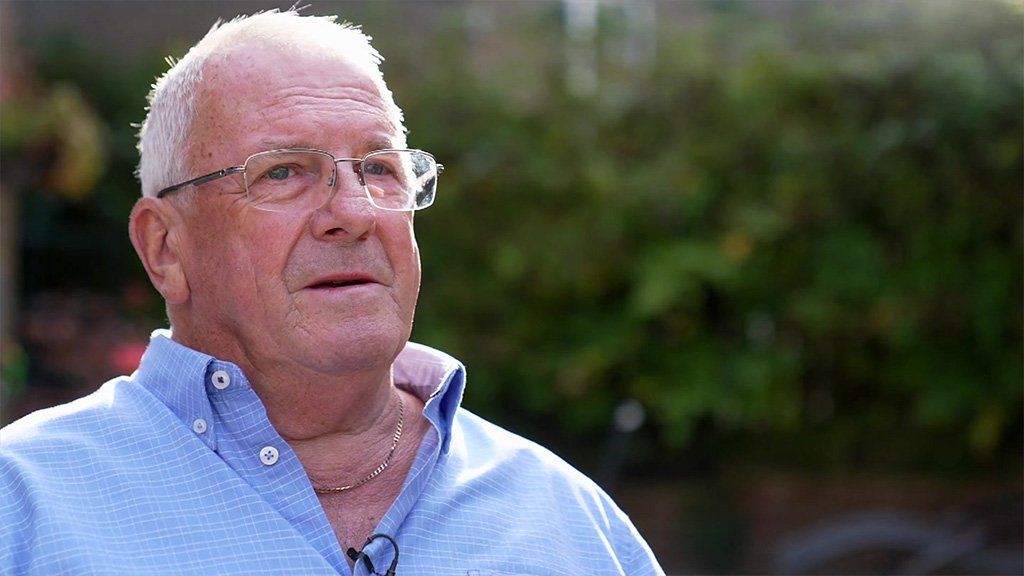

Some people who pay for their own care at home have had to cut back on visits to support their basic needs, such as help with washing, dressing and medication. And with NHS waiting lists at record levels, patients, like Dave Lockyer from Burley in Wharfedale, near Bradford, have had to use their savings or pensions to pay for their operations.

The 65-year-old paid around £15,500 to have his hip operation performed privately in June.

‘I simply wouldn’t have lasted’

He says he did this out of desperation, because he couldn’t face waiting in pain for longer – he was told the NHS waiting list was around two years.

Dave had injured his hip almost a year earlier, helping a neighbour lift a sick relative who had fallen.

While waiting for his operation Dave missed being able to walk the dog and says he couldn’t even put on his shoes.

“The pain was 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It just got worse and worse, and the painkillers got stronger and stronger,” he said.

He says at that time the pain was so intense he spent most of his time in bed.

“I was a shell of myself. Along the way, my mental health got worse. I simply wouldn’t have lasted two years.”

Recent research by YouGov of more than 8,000 adults suggests one in eight Britons have used private care in the past 12 months. And eight in 10 of those say they would previously have used the NHS.

The CQC report also says that in a survey of 63,000 hospital inpatients, 41% said they felt their health deteriorated whilst they were waiting for treatment.

The report warns of a “notable decline” in maternity, mental health and ambulance services:

- Almost 50% of maternity services are inadequate or need improvement

- Black and Asian women and babies continue to experience higher risks around birth, with infant mortality rates for both still higher than any other group

- Ambulance services are performing worse too, with a rise in the number ranked inadequate for safety

- In mental health, a lack of community care and inpatient beds means some people in crisis are having to go to A&E

For the second year, the CQC describes the social care system, that supports people in their own homes or in care homes, as “gridlocked”.

The government says it is investing record amounts into health and social care services to improve access to care and cut waiting lists.

“This includes up to £8.1 billion to put the adult social care system on a stronger footing,” a spokesperson said.

The CQC report points to ongoing difficulties recruiting staff. It also says council budgets have failed to keep pace with rising costs and the number of people needing support. It warns that people, particularly in less wealthy areas where more rely on local authority social care, may not be able to get the support they need.

Some patients cannot leave hospital when they are ready, it said, because of a lack of support in the community.

Kath, who is 85, spent several months stuck in hospital then a care home, before she was able to return to her home because her local authority couldn’t find the home care she needed to support her.

And 75-year-old Christine Lee, who has multiple sclerosis, remains in a care home because her council and care company say they can’t provide her with enough support in her specially adapted flat.

Christine’s daughter, Linda Taylor, says she has repeatedly told professionals she wants to go home, and that her mother feels like “she is living in a prison”.

The report also warns that some people who pay for their own social care are being forced to reduce the support they get because of cost of living pressures and rising prices.

The CQC’s chief executive, Ian Trenholm, says the annual report shows health inequalities are being exacerbated by the current pressures on health and care.

“The combination of the cost-of-living crisis and workforce challenges are leading to an increased risk of unfair care,” he says.

“I don’t know what I would have done without these lasses,” says 85-year-old Kath.

She and care worker Michelle Rispin laugh and joke with each other, as Michelle busies herself checking Kath has the food and help she needs.

Kath is back at home now after being stuck for several months in hospital and then a care home

This Cleveland home where she brought her family up is where Kath wants to be, but the gridlock in social care described in today’s report left her worried she might never return home.

She spent several months stuck in hospital, then in a care home, because of a lack of the care staff she needed to support her in her own home.

“I kept saying to them why is it so hard, they said they can’t get the lasses to do the job.”

She is very clear in her own mind why that is – “they can’t pay them enough,” she concludes.

Whilst in hospital, because she was spending most of her time in bed, her ability to look after herself deteriorated. “I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t do nothing for myself, they had to do everything for me.”

To get home she had to learn to walk again. Now, with four care visits a day, she is doing well.

‘We lose people to work in supermarkets’

Michelle Rispin started working in care at the start of the year.

“It really is a hard job,” she says. “And you’ve got to put your heart into this job. But once you get going, it’s just fantastic.”

Kath doesn’t know where she would be without carers like Michelle

Even so, she says the pay is “rubbish” and that many people cannot survive on it.

Her boss, Michelle Jackson of Caremark Redcar and Cleveland agrees that care staff should be paid more, but says they pay as much as they can on the fees they get. Nearly all their work is for local authorities.

“We lose people to work in supermarkets, care homes, sometimes, to the NHS,” she says. She believes elsewhere people can get paid “a lot more for doing a less responsible job”.

The BBC first spoke to Michelle Jackson 18 months ago, when she was having to turn people needing care away because she didn’t have enough staff.

“When we spoke in May 2022, we were turning away, probably about 60% of the work (from the council),” she says. “And it’s probably about the same now. We can’t take work on if we don’t have the staff to be able to do that work safely.”

The consequence, she says, is that people end up with no choice about where they live, and it adds to the pressure on the NHS.

“We’re always bumping from crisis to crisis, from day to day,” Michelle says, “and it just needs to stop.”

‘They talk over me’

Christine Lee, who is 75, believes she has been robbed of choice over where she lives.

For 15 years she enjoyed life in her specially adapted home in Norfolk. Now she lives in a care home and is desperate to leave.

She has multiple sclerosis, so her housing association flat was kitted out with hoists and all the equipment she needed. She also got 13 hours of support from a care company.

“I was told that’s a home for life and they could meet all care needs,” she says. “I had my own lounge and my friends used to come round and have a cup of tea. That was good.”

Christine is desperate to return home

But whilst she was in hospital last year, she was told that the care company could not provide her with the level of support she needs. She was moved to a care home. It was meant to be short-term, but she was there a year.

She’s since moved to another care home nearer her daughter, but remains desperate to return to her flat.

She feels she hasn’t been listened to. “They talk over me,” she says. “I’m on medication for depression because I’m feeling very sad and lonely. I just want to go home. That’s all. I want to go home.”

She and her daughter, Linda Taylor, believe she probably needs 17 hours of help a week.

Linda says that a year ago, she wouldn’t have believed the situation her mother is in now.

“I feel mum’s human rights have been completely ignored,” she says.

“She feels as if she’s been kidnapped. That’s her words. It’s been absolutely heartbreaking.”

The care company, Norse Care, says it strives to ensure people have the best possible care.

“In very rare cases such as this one,” it says, “we felt it was in the resident’s best interest to be supported in a new home which was better equipped to meet the resident and relative’s needs.”

Norfolk County Council says it offered Mrs Lee several care home places and has “acted entirely within the requirements set out in the Care Act throughout”.