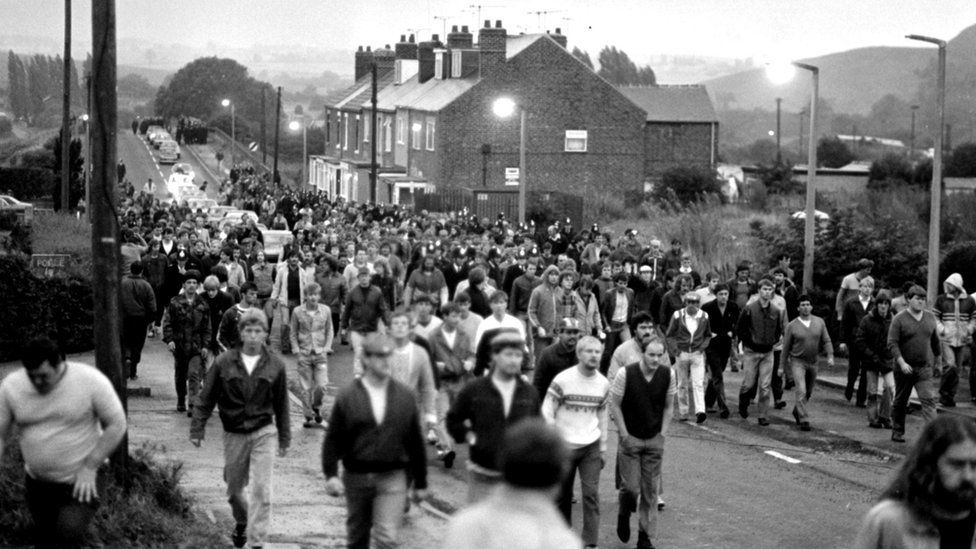

Striking miners in Kiveton Park, South Yorkshire

By Chris Baynes, Stephanie Miskin & Nicola Rees

BBC Yorkshire Investigations

Driving home from his last shift down the pit, as Britain’s coal industry withered away, Don Keating pulled into a lay-by and cried.

“It broke my bloody heart, honestly. All we’ve gone through and suddenly there was this massive void,” said the former South Yorkshire miner. “I didn’t know what I was going do.”

Mr Keating, now 76, had spent a year on the frontline of one of the longest and most acrimonious industrial disputes in the country’s history.

He was among the first men to walk out on strike in March 1984 after learning of the government’s plans to shut Cortonwood colliery, near Rotherham, and 19 other pits – some within weeks.

More than 140,000 other miners across Britain soon joined them in downing tools. Many went unpaid for 12 months as the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), led by Arthur Scargill, fought to stop a colliery closure programme backed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

During that year, families struggled to afford food, clothe their children and heat their homes. They relied on community donations to survive, with miners’ wives running soup kitchens, collecting money and food, and rallying support.

“There was a lot of heartache,” said ex-miner Terry Cadwallander, whose brother took his own life while on strike. “But we still had to keep going.”

Britain’s coal mining industry employed more than 220,00 people before the strike

For those involved, memories of the strike – and the pit closures which followed the union’s defeat – remain raw 40 years on.

In new interviews with the BBC, former miners, family members, police, journalists and politicians tell the story of the battle which changed Britain and its coalfield communities forever.

Warning: contains strong language

‘A slap in the face’

In March 1984, the National Coal Board (NCB) announced plans to shut 20 pits – which it said were unprofitable – with the loss of at least 20,000 jobs. Workers at Cortonwood colliery in Brampton Bierlow – earmarked to close within weeks – walked out on strike, followed by miners across Yorkshire and other parts of England, Scotland and Wales.

Dave Creamer, miner at Silverwood colliery, South Yorkshire: “We knew it were coming. There’d already been an overtime ban for three to four months before the strike. Everybody seemed to know it was coming, they just didn’t know when.”

Don Keating, miner at Cortonwood colliery, South Yorkshire: “I was doing a 6 o’clock evening shift with a mate. I’m walking down Pit Lane and a couple of lads who were coming up off shift said, ‘Don, do you know pit’s shutting?’ A bit of a joke, we thought – more rumours. We got down there and… they were saying, yeah, it’s been announced that Cortonwood will be shutting.”

Jackie Keating, Don’s wife: “I remember it vividly. Don came home in the early hours and woke me up. He never normally woke me up, he used to sneak in bed. He says, ‘I’ve got you a cup of tea ready. I need to talk to you.’ I came downstairs and he told me, ‘They’re closing the mine’. It was shocking.”

Image source, Supplied

Jackie and Don Keating had two young children when the strike began

Don Keating: “The following morning we were called to the working men’s club in the village for a meeting and we were told by the union what had gone off… It took everybody by surprise. It was such a slap in the face. Six weeks earlier there’d been a review of the pit which said it would last another five years. People have got families, they’ve got lives, and they can plan. Suddenly to have that slapped on you, you haven’t really got time to think.”

Chris Kitchen, miner at Wheldale colliery, West Yorkshire, and NUM secretary since 2007: “We came straight out. I was 17 – to me, at that age, it was just another dispute. I took my lead from my dad, who worked there, and some of the older guys. They didn’t seem concerned… We’d resolve the dispute and be back at work.”

Bill Rose, miner at Markham Main colliery, South Yorkshire: “I had an extension put on my house and the bloke doing it said, ‘Oh you’re on strike, I’ll wait a while’. I said, ‘No don’t worry, it will only last a month or two.'”

Image source, Getty Images

The picket at Cortonwood colliery became known as the Alamo

‘There was a lot of heartache but we had to keep going’

As the strike stretched from weeks into months, mining families counted the cost of going unpaid.

Trevor Barnard, electrician at Markham Main: “It was hard, I mean it was like living back in the 1800s where you scrimped and scraped. You tried to save on everything you could.”

Jackie Keating: “To realise that, three weeks from now, you’re not going to have a penny coming in is an enormous thing. To realise that you’re not going to have anything and you’ve got to clean and clothe your children and feed them on a very small amount from the dole.”

Image source, Alain Nogues/Getty Images

A welfare centre was set up at Cortonwood so miners’ families could eat

Don Keating: “I was a part-time fireman so we had a little bit of money coming in. You didn’t get a lot of money – a retainer wasn’t a lot. But every little bit helped… It was a way to get some money for Christmas, for the kids, et cetera. And, of course, there was keeping the house warm as well, because your coal allowance was stopped.”

Aggie Currie, wife of Markham Main miner: “Buying a Christmas tree was out of the question. I’m thinking my kids are going to have no bleeding Christmas tree, they’ve hardly got owt for Christmas. I went upstairs because I was crying and I didn’t want kids to see me upset. I’m looking out the window and I looked at next door’s garden and they’ve got a tree… I thought, that would make a good Christmas tree. Two o’clock in the morning, I went and fucking sawed it down. And do you know, that lad never mentioned anything to me. He must have known it were me.”

Image source, Getty Images

Miners were refused their coal allowance while striking and scavenged for loose coal around mines to use as fuel

Dave Creamer: “I was 23, single and living with my mum and dad so I got it fairly easy myself. They really carried me, like. My dad were a steel worker so he knew about striking.”

Chris Kitchen: “My dad, three of my uncles and a couple of my cousins all worked at Wheldale at that time, which is not good when you’re all on strike and nobody’s got any money. My mum was working two jobs. She worked in a newsagents in the morning and she worked behind the bar at night.”

Jackie Keating: “Don lost a lot of weight, he just went so thin. It was shocking to see a lot of the men lose their muscle, because when they worked down the mine they had to do a lot of heavy manual work. And they were losing the mass of their bodies because there weren’t enough food to go round – you’d give it to your children. It was pretty bleak.”

Steve Houghton, engineer at Grimethorpe colliery, South Yorkshire, and Barnsley Council leader since 1996: “People lost their homes, people ended up with divorces. It broke families. It was an incredibly, incredibly difficult time. People lost all their savings. I had to sell my car to get some money in, which was nothing compared to some.”

Image source, Alain Nogues/Getty Images

Striking miners and their families could eat food at Cortonwood miners’ welfare centre

Bruce Wilson, miner at Silverwood: “One of the lads we used to go picketing with, in summer ’84 him and his wife lost a baby. It was two weeks old. He went to DSS to ask for help, some funds to bury his child, and they refused. They said anybody who was involved in industrial action – friends, family, whatever – they’re not entitled to any help. My mate says, ‘What am I supposed to do, bury the baby in the back garden?'”

Terry Cadwallander, miner at Goldthorpe colliery, South Yorkshire: “There was a lot of heartache. My brother Geoffrey committed suicide. He couldn’t cope… He’d got three kiddies and his wife had come from Exeter and she went back down to Exeter and it was killing him not seeing his family, not seeing his kids… Obviously times were hard and my brother couldn’t afford to tax and insure his car. So he couldn’t go down to see them and it just got too much for him. I had to break that to my mam and dad. There was a lot of people who lost people through the strike, through the same circumstances. But we still had to keep going.”

Terry Cadwallander’s brother Geoffrey took his own life during the strike

‘In my heart I knew I had to do something’

Miners’ families relied on donations from their communities to survive. Wives ran soup kitchens, collected food and money, and held rallies to drum up support.

Aggie Currie: “It was important to me because my dad was a miner, all my dad’s brothers were miners, my husband Pete’s dad was a miner. In my heart I knew I had to do something.”

Bruce Wilson: “We weren’t just fighting for my job and my community. We were fighting for your mate’s job and community down the road.”

Image source, Supplied/BBC

Aggie Currie travelled across Britain and abroad as a spokesperson for Women Against Pit Closures

Terry Cadwallander: “Nobody expected to be out nearly 13 months on strike. It was tough but everyone was close and helped each other. I used to go every afternoon to Manvers coking plant, there was hundreds of tonnes which had fallen off so everyone went with their sacks and spades and went coaling. I got seven bags a day and gave it to people who needed it.”

Dennis Norwell, blacksmith at Markham Main: “Nobody would let the police in the shops or in the pub, the Taddy. They said, ‘We’ve got to live here when you’ve gone.’ Everybody stuck together.”

Image source, PA Media

Miners’ wives rallied in support of striking workers

Trevor Barnard: “We’re a proud village and we had a community. There were local businesses donating money, food for the food banks, parcels for the kids at Christmas. There was a baker down the road making bread and pasties and he would give them to the food bank throughout the day. There were collections going out all over… We wouldn’t have managed as long without them.”

Jackie Keating: “I’ve always liked catering for everybody and it was a natural extension to being a mum, that’s how I saw it. To keep bright and busy and to stick together and everybody help each other out.”

Aggie Currie: “Maggie Thatcher, I hate her with a vengeance. They call her the Iron Lady, but you know something? She didn’t expect hundreds of iron ladies.”

Image source, Alain Nogues/Getty Images

Miners’ wives prepare packages of donated food for at Kiveton Park miners’ club, South Yorkshire

Jackie Keating: “Don wouldn’t go to the food kitchens, we’d argue about us accepting help because he’s such a proud man. He saw it as us taking from who’s worse than we were.”

Don Keating: “In October it was my son’s birthday and he was mad on the Transformer cars… A new one had come out and by God did he want it. There was absolutely no way I could afford it. I must have mentioned it at the fire station – not because I wanted anyone to buy it for him. On the day of my son’s birthday there was a knock on the back door just before nine in the morning and it was Frank, who was a full-time fireman up there. And would you believe it, he’d gone out and bought it him. Things like that, I feel quite choked thinking about it now.”

Image source, Getty Images

Women sort through donations at Kiveton Park miners’ club

Steve Houghton: “I don’t want people to underestimate how difficult it was… Our families struggled. The fact they kept that going for a year was huge testimony to their anger but also their determination to try and protect what they’d got.”

Russell Broomhead, miner at Houghton Main colliery, South Yorkshire: “We were just fighting to save an industry, we weren’t after a pay rise… It was a war of attrition, really, just keeping going making sure the family were fed and safe. That’s all it were, really, until what happened at Orgreave catapulted us all into the national media.”

‘A state of civil war’

The NUM sent protesters – known as flying pickets – to disrupt and pressure working miners. While most picket lines were relatively peaceful,violence flared between striking miners and police as tensions grew. Officers were drafted in from across the country in a coordinated national policing operation.

Dave Creamer: “We were setting off at four o’clock picketing, trying to get through roadblocks… We went through every back alley you could think of, up farmers’ fields, down through woods – everything – just to get to that picket line. Sometimes we got through, sometimes we didn’t. It was quite an adventure at first. I was 20-odd-year-old, it was exciting. The adventure became a bit of a nightmare later on.”

Chris Kitchen: “We’d go to the strike centre, which was at Townville club for us, in the morning, and then we’d be given directions to the mine or the workshops we were picketing… You’d play cat-and-mouse with the police, who were trying to turn you back.”

Image source, Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Picketers played “cat and mouse” with police as they attempted to stop workers getting to pits

Dave Creamer: “You tried all sorts. Fishing. And [the police] said, ‘Where’s your fishing tackle? Empty the boot.’ Sometimes we were a bit daft, we’d wear the flat cap and Support the Miners badges stuck all over us.”

Tony Munday, Hertfordshire Police officer: “To begin with, we were dealing with flying pickets. You’d get some distance away on side roads into the colliery villages. You’d get a carload of pretty burly men all from Yorkshire… Apparently they’re all going fishing, but nobody had a rod! You just sort of shook your head and said, ‘Sorry, fishing’s off at the moment’.”

Richard Wells, BBC Look North journalist: “The strike was due to start at 6’clock in the morning and I was dispatched to go to Woolley colliery because it was the pit where Arthur Scargill earned his stripes… I ventured up to a picket line and as fast as I walked up, I was lifted off the picket line by a couple of burly miners, one of whom got hold of my lapels, marched me off the picket line and said: ‘We don’t want the media here because they’re biased against the strike’… So I knew I was going to be in for a bumpy ride.”

Image source, John Rogers/Getty Images

Police clash with picketers outside the NUM office in Sheffield

Aggie Currie: “The very first picket line I went on was Harworth pit. Believe it or not, I didn’t swear before the strike – but I soon picked the language up.”

Mike McKay, journalist for BBC News in London: “I remember particularly one very early morning, I was driving up the A1, and on the other side of the road was this endless convoy of police riot vans. It just went on and on. It just looked such a formidable force. It resonated with the description that was later used about this as virtually a state of civil war. It was like you were watching an occupying army travelling to the front.”

Tony Munday, police officer: “We were put up in military camps… For the evening meal, there was always a curry and a choice of three things. You were given a packed lunch because you were out during the day. As it went on, you became aware that these [miners] were proud people being starved back to work. It was a bit iniquitous, really… I used to give my lunch packs away.”

Image source, Alain Nogues/Getty Images

Miners clash with police in Woolley

Chris Kitchen: “Picket lines, at the start, they weren’t violent. You’d turn up, there’d be a couple of police knocking about and then you’d get a bigger police presence at shift changeover times and there might be a bit of a push and a shove. And then you’d go home… Later on, riot shields became the norm at most of the bigger pickets.”

Dave Creamer: “The pushing and shoving started when the strike breakers were coming in, in the buses et cetera. That’s usually when the police would pull out the truncheons or let the dogs go. When it got a bit heated, the riot shields would be out and the horses and you’d get charged. It became quite violent at times and a bit scary.”

Lord Heseltine, minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government: “A significant number of miners wanted to work and were prevented from doing so by the flying pickets… And that’s a powerful argument as why the government had to make sure this sort of activity stopped… There was at work a group of people outside the rule of law, who thought that they could achieve their purposes by thuggery of one sort of another.”

Image source, PA Media

Michael Heseltine, defence secretary at the time of the strike, said he kept a “very low profile” as “we didn’t want any headlines about the troops being brought in”

Trevor Barnard: “The police, they were horrible… They was wading into us with batons and shields, kicking us, but as soon as you fought back, you was locked up for it.”

Dennis Norwell “The police used to run round this village with shields, banging on them: boom, boom, boom. Frightening kids. It wasn’t right. They used to shove their pay packets in your faces, that was the worst thing, saying ‘Look what we’ve got here and you’re on strike’. And we had nowt.”

Dave Creamer: “I nearly got my head caved in at Beavercotes colliery in Nottingham when they just withdrew the truncheons for no real reason. There were only a bit of shoving and pushing going on, it was good-humoured. I managed to keep my head just out of the way.”

Aggie Currie: “One picket line I went on, I got smacked in the mouth by a copper. Lost my tooth and got a black eye as well… I was arrested 17 or 18 times. Not once did we get charged because they didn’t want to make miners’ wives look martyrs.”

Image source, Supplied

Aggie Currie, left, was arrested along with other miners’ wives during the strike

‘I thought I was going to die’

In June 1984, thousands of miners from across Britain picketed at Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire in a bid to stop lorries delivering coal and collecting coke for Scunthorpe power plant. On 18 June, tensions reached boiling point. Police in riot gear on mounted horses charged at miners, leading to violent clashes. Ninety-five people were arrested and charged with riot and violent disorder. All were later cleared.

Russell Broomhead: “We set off as normal, quite early. But what were very strange was police actually helped you get there. Where they’d always turned you away and put roadblocks on, they actually helped you get there and told you where to park. It was very surreal really. With hindsight, we should have known something were going to happen.”

Chris Kitchen: “We parked up at the estate at the top, walked down over the bridge. There were quite a few pickets already there but they were outnumbered by police, who were already lined up about three or four rows deep.”

At least 6,000 miners faced off against police at Orgreave coking plant on 18 June, 1984

Tony Munday, police officer: “There was a hell of a lot of police, but I’d no idea what we were going to be doing until we got out. All we had was the custodian helmets – the peaked hats – no protective equipment, no shields and in those days you had your truncheon… We were there to be lined up.”

Richard Wells, journalist: “That was, I suppose, Scargill’s Waterloo. That was where the strike was going to be won or lost… Every day the tension was a little bit more than the day before.”

Image source, PA Media

An estimated 6,000 police officers confronted miners at what became known as the Battle of Orgreave

Tony Munday: “At some point, there was a hell of a lot of bricks and other things being thrown in our direction. My main concern was just to look down to the ground because I didn’t want to be blinded. We were almost like skittles, completely defenceless… Not knowing what the strategy was of the people in charge, we’re thinking ‘Are we just cannon fodder?’… And then there was a parting of the ways, someone shouted out, and officers on horseback went through, followed by others with short shields.”

Alex Matthewson, miner at Barnburgh Main colliery, South Yorkshire: “When the horses came through, I tell you this now, without a word of a lie, I ran for my life.”

Richard Wells, journalist: “We followed the police horses and there was obviously a big fight involving police, a lot of them mounted, hitting miners. Then the horses retreated back to the police lines, and we were caught in no man’s land, and of course some of the miners came out and had a dig at us.”

Image source, Getty Images

Campaigners have long demanded an inquiry into policing at Orgreave

Dave Creamer: “There were some pickets that were really badly behaved… but it was usually fetched on after they’d been charged or nearly run over by a horse. It was tit-for-tat retaliation. At Orgreave, the police just went berserk. They must have been given orders to roll ahead and do what they’ve got to do at all costs. That must have come from high up.”

Alex Matthewson: “It was like a war zone… All you could see was miners running up bankings, over railway lines, all over. And the police just hitting anybody, arresting anybody… Some of the lads, when we saw them getting put in the van, there was blood all over them. It was terrible.”

Don Keating: “Somebody got me by the hair and dragged me to the ground, this copper. Before I knew it, there was four on me. One had got his lock around my neck. I thought I was going to bloody die, I just could not breathe. I made him aware and – to give him his due – he did ease off and he carried me to the bus and handcuffed me… I was charged with unlawful assembly, to be upgraded to riotous assembly. One of my conditions of bail was to not picket anywhere but my own pit, so I never went flying again.”

Image source, PA Media

An injured picketer is carried away by paramedics at Orgreave

Tony Munday: “At the end of the day they said people who had arrested someone had to go to this particular area which looked like a school hall and that’s when it all really started to unravel… We sit down to write the statement and someone came in in plain clothes – a senior officer from South Yorkshire – and said, ‘Right, we need you to open your statement with these couple of paragraphs’. I said, ‘What’s this all about? That’s not how it’s done.’ [He said], ‘This isn’t a request, this is an order’. He then started dictating and I could tell what was being dictated were the ingredients of the offence of riot.”

Don Keating: “They kept us on bail for nearly another year before they dropped all the charges… We knew we weren’t guilty of rioting. Yes, we were noisy, yes were boisterous, but I can honestly say as I’m stood here now I never threw a brick, I never hit a copper. My arrest was totally unjustified. It was a way of keeping pickets off the picket line.”

‘A horrible situation’

Arthur Scargill vetoed a national ballot on the strike, allowing regional NUM votes instead. In Nottinghamshire, parts of Derbyshire and North Wales, miners voted against joining the walkout and many carried on working. They were known as “scabs” by striking miners, who picketed as they arrived at work. Peter Short, a union official, was among those who worked.

Peter Short, electrician at Bilsthorpe colliery, Nottinghamshire: “I voted to strike, but it was what it was. We weren’t going to go on strike without a ballot.”

Tony Munday, police officer: “North Derbyshire was the most difficult place to police. There would be people who would turn up expressing their unhappiness at the people going to work. There was lots of shouting, lots of swearing, people pushing and shoving… You could tell that these were families who were split and they were split from their own union.”

Image source, NCJ Archive/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Picketers attempt to stop a bus carrying working miners to Ellington colliery in Northumberland

Peter Short: “I’m a fairly robust character, but I know for some others it was extremely frightening and intimidating just to go past this big group of people. The noise was a lot.”

Aggie Currie: “On 22 August, we got scabs in our pit… It was a horrible day. I’m there shouting my fucking head off… chucking paint bombs.”

Image source, Getty Images

A worked miner’s house in Bolton upon Dearne, South Yorkshire, boarded up and daubed with graffiti

Peter Short: “There would be people who didn’t talk to me for a long time… Some of my family still worked in mining in the North East. I had family who lived in Ollerton who were on strike. There was a cooling of relations.”

Don Keating, striking miner: “My brother-in-law worked in Calverton pit in Nottingham. They didn’t come out. I didn’t speak to him. I didn’t fall out with him but… I never spoke to him again. I had no intentions. That part of my family, we’re still, shall we say, estranged.”

Trevor Barnard, striking miner: “They’re scabs, still the same. No love lost. Once a scab, always a scab. You’ll never lose that name, never.”

Peter Short: “It was a horrible situation. Thatcher set out to do what she did… It put people at each other’s throats.”

Image source, Supplied

Peter Short, centre, pictured with dad Eddie, who was also a miner

Don Keating: “They were promised all sorts of things, like a lot of the Nottinghamshire coalfield, so never came out. As soon as the strike finished, guess what? They shut their pit, as they promised they wouldn’t.”

Alex Matthewson, striking miner: “Personally I knew two or three people who had gone in to work… They were conscientious, regular-working family miners who had been shoved to the brink.”

Don Keating: “There was a lad who lives about half a mile from where I live now. He went back to work about a week before the strike ended. Two days after the pit eventually went back to work officially, he was found hanging through the loft hatch by his neck… He was 27, a young man. It wrecked his family. Absolutely awful. They’ve all got their own reasons for going back.”

‘Heads held high’

After a year on strike, a growing number of miners were choosing to return to work. On 3 March,1984, NUM leaders voted to end the dispute without an agreement with the NCB and instructed members to go back to work.

Alex Matthewson: “As the strike went on, it was clear as day we weren’t going to win it. Margaret Thatcher was going to crush the miners, one way or another.”

Dave Creamer: “The night they held that branch meeting, when the orders came through from national level to go back to work, the club was nearly turned inside out… There was almost fighting inside the club with people that wanted to stay out, people that wanted to go back… It was one of the angriest meetings I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Trevor Barnard: “When the strike was called off, our pit stayed out for another week. We was the last pit back, I believe… Everybody who worked at the pit, and a lot of the wives and helpers, marched up our main road with our heads held high, singing with a brass band. People were coming out their houses and shops clapping us. We went through those pit gates proud we’d stuck it out.”

Image source, Peter Davies

Goldthorpe miners return to work after the strike ends

Dave Creamer: “In the end everybody accepted the orders… But when we marched back the next day, that was a very quiet, solemn affair. No shouting, no singing. Everybody just marched behind that banner through Dalton, through Thrybergh, to the pit head… It was the disappointment of knowing you’ve been well-defeated and you’ve had a damn good hiding.”

Trevor Barnard: “I refuse to call it a defeat. We lost, but I’ll not call it a defeat. Thatcher knew she had been in a fight with people… She didn’t break us because we came back and we built the village again. We found work.”

Trevor Barnard said he was “very proud” of the way the people of Armthorpe came together

‘This massive void’

By the end of 1985, 23 pits including Cortonwood had shut. Ninety-seven further closures followed before the coal industry was privatised in 1994. The UK’s last deep coal mine shut in 2015.

Aggie Currie: “They killed this village. Not just my village, all mining villages they killed.”

Don Keating: “I was frightened to death of working underground for a private enterprise, cutting corners, cutting costs. I decided to take my redundancy. It really upsets me when I think about it. I came out the pit that morning and pulled into a lay-by. It broke my bloody heart, honestly. All we’ve gone through and suddenly there was this massive void. I didn’t know what I was going do, I didn’t know where I was going to go. I just sat there and I cried my eyes out.”

Image source, Colin McPherson/Getty Images

Monktonhall colliery in Midlothian closed in 1987 and was later demolished

Lord Heseltine, government minister who announced closure of 31 mines in 1992: “My personal view was one of great sadness to have to take a decision which everybody knew was coming. Frankly, the miners knew there was an end to coal production for economic reasons. They knew it was going to happen. That doesn’t make it any easier or any less unpleasant. It was simply a fact of economic life.”

John Hays, miner at Goldthorpe: “We got redundancy and a nice lump sum of money but the thing is, it was the after. There was nothing. There was nothing there for us.”

Bill Rose: “I never worked again. I was 49. The thing with miners is, you work down the pit for a long time, you don’t think you can work anywhere else other than down the mines.”

Jackie Keating: “People don’t realise that for several years afterwards we still suffered. We had to pay two mortgages for a year to catch up, which was really, really hard.”

John Hays: “Look at it now, they were going to close anyway, what with fossil fuels, but it was hard. Bang, six months – it was shut… Nobody had any trades – odd one was a plumber or electrician but for us it was factories or the post.”

Chris Kitchen, general secretary of the NUM, said he would always be proud of the strike

Chris Kitchen: “I’m still proud of the actions I took and nothing will take away that pride. When you look at the way the industry and communities have been decimated, I think that justifies it was the right thing to do to stand up and fight.”

Don Keating: “If you can honestly say, hand on heart, that you tried to do your best for your family, then I don’t think you can go far wrong. And I feel quite proud about that.”

Image source, Supplied

Don Keating, who went on to work as a care home manager and phlebotomist, said he had no regrets over the strike