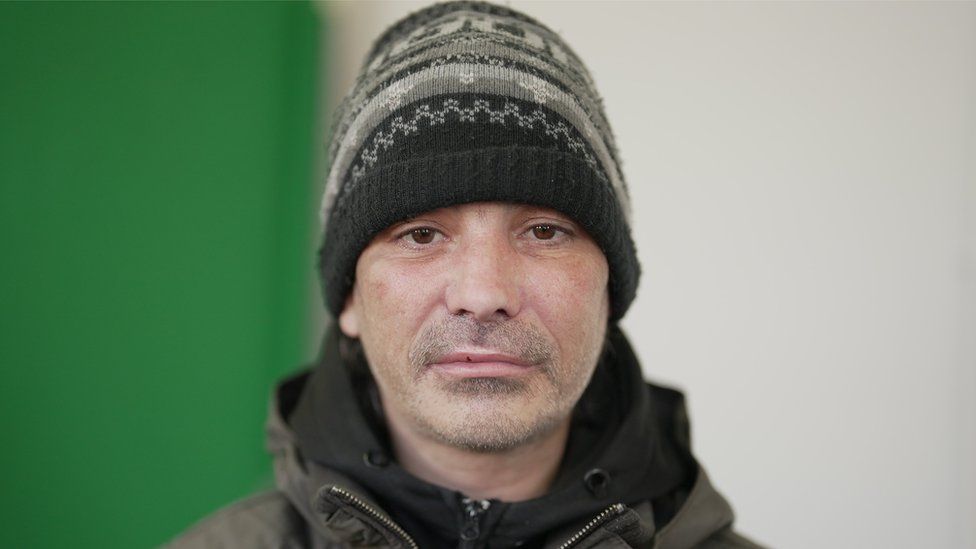

Paul is about to embark on a tough detox journey

By Dominic Hughes & Natalie Wright

Health correspondent, BBC News

“Hugging my mum again. I’d love that. That would be special.”

Tears are streaming down Paul Earnshaw’s face as he talks to us.

He has struggled for years with alcohol, but is now trying to break free from his addiction.

It is going to be a tough journey.

The road to recovery

The enormity of what lies ahead is sinking in.

Paul is about to start a detox course, followed by what could be up to six months of rehab.

“I need to do it. I won’t let nobody down. I won’t let myself down.”

Sitting on a sofa in the Blackpool offices of the charity Empowerment, Paul is reflecting on where he has ended up.

Paul’s support worker Dave (r) has played a vital role in helping him reach this point in his recovery

“I don’t want to be picking a can up every single day, walking around the streets, people thinking, ‘oh, look at him, he’s drinking again, still doing this, still doing that’.

“Nah, I don’t want to do that. I’m 40 years old, I’m not getting any younger. It’s time to move on, it’s time to live my life a different way. It’s an opportunity – if I don’t take it, I’ll never get it again, but I’m taking it, I’m doing it.”

At one point Dave, Paul’s support worker, gives him a huge hug, and for a moment you feel Paul may never let go.

‘Deaths of despair’

Blackpool is a town plagued by too many preventable fatalities linked to alcohol, drug abuse and suicide – collectively described by the bleakly poetic phrase “deaths of despair” by health researchers.

A study of deaths recorded at coroners’ courts across England suggests that between 2019 and 2021, about 46,200 people lost their lives in this way – the equivalent of 42 people every day.

And research suggests Paul’s hometown of Blackpool has the highest rate of these deaths.

In Blackpool the rate is 83.8 for every 100,000 deaths.

Compare that to the area with the lowest rate, Barnet in Greater London, where the figure stands at 14.5 deaths per 100,000.

Steven Brown, a senior member of the Empowerment team, has lived a similar life to Paul, and against the odds, has somehow come out the other side.

“I’m from a council estate in Layton in Blackpool, and I started hanging around with older people, my brother, and most of us started taking drugs, and then a lot of us couldn’t stop taking drugs,” he said.

“I was stuck in that revolving door cycle that I couldn’t get out [of].”

The drugs led to crime, which led to prison, but after more than 20 years spent in and out of jail, a key moment came when Steven went to a prison talk by a former addict who was running a charity for ex-offenders.

Steven, who grew up in Blackpool, has survived a life of addiction and is now helping others get clean

“I didn’t know that people recovered. You either went to prison – you got locked up – or you died.

“Having some hope from someone like me, who hadn’t been to college and wasn’t educated – and I knew that they’d walked in the steps that I’d walked in – they was talking my language.

“And it’s that hope of, ‘how have you done it? I want what you have. How do I follow you?’ and I guess that little bit of hope changed my life.”

While he was in recovery, someone told Steven he only needed to change one thing in his life: “Everything – people, places and things.” Steven understood what his friend meant.

Everyone in the Empowerment team has what is known as “lived experience”, meaning they have all lived the chaotic and dangerous lives of the addicts, homeless people and alcoholics they are now helping.

Clean for more than seven years, Steven’s life now could not be more different from the one he left behind – a steady job that he loves, a partner, a child, a home.

Wealthy but unequal

New analysis led by academics from the University of Manchester, the National Institute for Health and Care Research and a consortium of universities and NHS hospital trusts across the north of England, mapped the deaths to local council areas and calculated what factors increased the risk of dying this way.

So being from the north, being white, male and working class, working in a manual job, having a lower level of education – all these are risk factors.

Image source, BBC News

Christine Camacho, the author of a report into deaths of despair, says underlying inequalities in health are making things worse

But as report author Christine Camacho explains, these factors combine to become more than the sum of their parts.

“It’s a bit like some of the effects that we saw in Covid where the pandemic exacerbated some of those underlying inequalities,” she said.

And the bad news for Blackpool, a northern seaside town, is that it has a higher rate of these deaths than anywhere else in England.

“The UK is a wealthy country, but it’s also quite an unfair country – our resources are not equally distributed. And deaths of despair are one avoidable consequence of that unequal distribution,” she added.

Breaking the cycle

There are 25 members of the Empowerment charity working in and around Blackpool, trying to offer that tiny bit of hope that transformed Steven’s life.

They operate alongside social workers, the town council and the local NHS, trying to find housing, healthcare and support, and offering practical help for the homeless, including supplying clothing and essential toiletries.

Helping prevent overdoses is also a crucial part of the work, with workers distributing the anti-overdose drug Naloxone, a treatment that Steven says saved his own life more than once.

The drug Naloxone can save someone’s life if they have overdosed on heroin

Support workers also build relationships of trust with people whose lives have descended into chaos.

Kate – not her real name – is now in her 30s, and said: “I started drink and drugs at a very young age, to the point of oblivion sometimes.”

For a while she was in rehab but dropped out and last autumn, she found herself pregnant, homeless and still in the grip of her addiction.

However, Kate’s support worker from Empowerment stuck with her and never gave up.

Blackpool has the highest rate of deaths linked to drugs, alcohol or suicide in England

Kate has been clean for more than 100 days and said: “It was extremely difficult, but I’d just had enough of living on the streets, being around needles in abandoned hotels, it was horrible.

“It was the change and the support from these guys that got me to where I am today, as well as myself. For someone to be there, and to have that support from when I was really bad in addiction, to now being clean, and having someone there regardless of whether I’m there or not, and still trying to support me, is an amazing feeling.

“If it hadn’t been for her, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Kate and Paul were both at risk of becoming statistics, but with the help of the Empowerment team they are beginning the long and difficult road to recovery.

Related Topics

Related Internet Links

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.