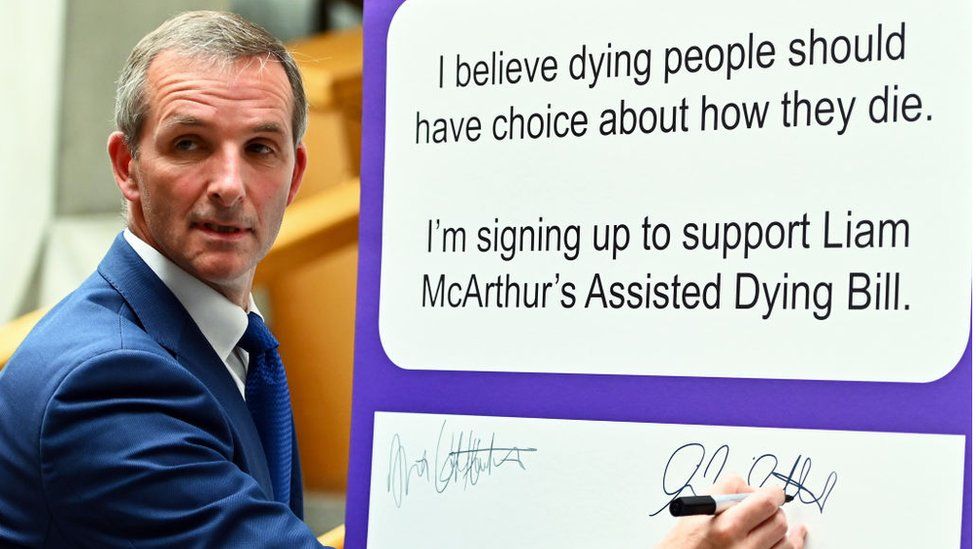

MSP Liam McArthur hopes his bill will be voted on in 2025

By James Cook

Scotland editor

Scotland could become the first UK nation to provide terminally-ill people with assistance to end their lives if a bill that has been introduced at Holyrood is approved.

Supporters of the legislation say it would ease suffering.

Opponents worry that some terminally-ill people could feel under pressure to end their lives.

The Assisted Dying Bill is drafted by the Lib Dem MSP, Liam McArthur, who expects it to be debated this autumn.

The bill was published on Thursday and will potentially be voted on next year.

The Scottish government says ministers and SNP backbenchers will not be instructed how to vote, as the matter is an issue of individual conscience.

First Minister Humza Yousaf, who is a Muslim, has indicated that he is likely to vote against the bill, which is also opposed by the Church of Scotland, the Catholic Church in Scotland, and the Scottish Association of Mosques.

Under the proposals, a patient could only request medical assistance to end their life if they had a terminal illness and had been ruled mentally fit to make the decision by two doctors.

Mr McArthur says “the terminal illness would need to be advanced and progressive” and the medics would have to ensure there was “no coercion.”

In addition, the patient must be aged 16 or over, a resident of Scotland for at least 12 months, and must administer the life-ending medication themselves.

In Scotland, it is not illegal to attempt suicide but helping someone take their own life could lead to prosecution for crimes such as murder, culpable homicide or offences under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

In England and Wales, the Suicide Act 1961 makes it an offence to encourage or assist the suicide or attempted suicide of another person. In 2015, the House of Commons decided against changing the law by 330 votes to 118.

In Northern Ireland, a similar offence is set out in the Criminal Justice Act 1966.

A number of countries have legalised some form of assisted dying – Dignity in Dying says more than 200 million people around the world have access.

This includes Switzerland, perhaps best known for its Dignitas facility, Australia, Canada, Spain, Colombia and 11 states in the US where it is known as “physician-assisted dying”. Laws vary by country.

This will be the third time that the Scottish Parliament has considered the issue.

In 2010, MSPs rejected Margo MacDonald’s End of Life Assistance Bill by 85 votes to 16.

The independent MSP, who had Parkinson’s Disease, died in 2014 and the cause was taken up by Patrick Harvie of the Scottish Greens.

The following year, his Assisted Suicide Bill was rejected by 82 votes to 36.

The title of Mr McArthur’s bill — Assisted Dying rather than Assisted Suicide — reflects a change in approach from campaigners.

Critics such as Dr Fiona MacCormick of the Association for Palliative Medicine (APM) say the new terminology is “harmful and unhelpful,” adding, “they’ve used very euphemistic language to talk about suicide.”

Dr Fiona MacCormick says she does not believe the answer to suffering is the end of the sufferer’s life

Mr McArthur says he would “strongly disagree,” because “we’re talking about people with a terminal illness, and the fact they are going to die has already been established.”

The MSP for Orkney Islands believes there has been a significant “mood shift” among his fellow parliamentarians since the issue was last debated and is hopeful that his proposal will be approved.

A new poll, carried out by Opinium Research for the campaign group Dignity in Dying, suggests clear public support for the proposal, with 78% of respondents in Scotland saying they supported “making it legal for someone to seek ‘assisted dying’ in the UK.”

Gillie Davison, whose husband Steve died with throat cancer last year – is in favour of a law change

Gillie Davison is among those supporters – her husband Steve died of throat cancer last April, at the age of 56.

Ms Davison, from Hawick in the Scottish Borders, says even high-quality palliative care did not ease his suffering in the final days and hours.

“It wasn’t a good death because he was distressed and he was upset,” she explains.

“It wasn’t what he wanted. He wanted that choice.”

She believes an assisted dying bill would have allowed her husband to “go to sleep” peacefully at home and could prevent other families from enduring a similarly “devastating” experience in future.

Changing the law, she says, would be “compassionate and kind.”

But Dr MacCormick says she is concerned about the potential for inaccurate diagnosis and prognosis, undetected coercion, and fluctuating mental capacity in seriously-ill patients.

“As a palliative care doctor, when I see patients who are suffering, I don’t see the answer to their suffering as being to end the life of the sufferer,” she says.

But some terminally-ill patients say they would find the option reassuring even if they did not use it.

Mandie Malcolm hopes a change in law would let her stop worrying about “dying a brutal death”

In 2015, at the age of 26, Mandie Malcolm from Falkirk was diagnosed with breast cancer which had spread to other parts of her body.

She was told that her life expectancy was two to five years.

Now 34, Ms Malcolm is still alive thanks to advances in cancer treatment but, she says, she lies awake at night worrying about how her life will end.

Until starting a new drug, she says, she was “bedridden for weeks and in huge amounts of pain.

“I really worry about my death. I worry that I’m going to suffer, horrifically, basically, and it does scare me,” she explains.

Ms Malcolm is strongly in favour of the assisted dying law, which she says would mean she could stop worrying about “dying a brutal death” and “enjoy the good times.”

“It would mean everything to me and my family,” she adds.

But campaigners against the measure point to laws enacted in Belgium and Canada where qualifying criteria have been loosened over time, leading to a sharp rise in the number of “assisted” deaths.

Mr McArthur says his proposed law is not modelled on those “permissive and expansive models” but on places such as the US state of Oregon where “the eligibility criteria has not changed at all” since becoming law in 1997.

He is supported by the broadcaster and campaigner, Dame Esther Rantzen, who recently revealed that she was considering travelling to Switzerland – where assisted suicide has been legal since 1942 – to die after being diagnosed with incurable lung cancer.

She says: “I want to congratulate the Scottish Parliament for prioritising this debate so that they can carefully consider this crucial issue and scrutinise this historic Assisted Dying Bill.”

Audrey Birt would prefer to see greater investment in palliative care

Audrey Birt from Edinburgh also has terminal cancer, the latest of five breast cancer diagnoses over 30 years, and has spent the past 12 years “in and out of hospital.”

But she does not want assistance to end her life and has concerns that, if the law is changed, some patients might feel that they must do so to help their families.

“In Scotland,” she says, “we don’t like to be a burden.

“That’s the aspect I worry about — that there may be pressure,” she explains.

Instead Ms Birt, who is 68 years old, says there should be increased investment in palliative care, which she receives at St Columba’s Hospice in Edinburgh.

“After coming here and being more aware of what’s on offer, I do wonder if it was available to everyone, would that take away some of the fear that is behind the bill?” she asks.

Helen Malo of the charity Hospice UK says her organisation is neutral on the bill but wants better funding of palliative care.

Hospices are facing huge funding challenges

Hospices support more than 21,000 people in Scotland each year, she says. But they are struggling, with only a third of their funding coming from the state, the rest from charitable donations, and rising costs.

“One in four people do not get access to specialist palliative care,” adds Ms Malo, who says that, as the nation ages, demand is expected to increase by a fifth by 2040.

“There are fewer specialist palliative care doctors in Scotland than there are MSPs,” says Dr MacCormick of the APM.

Without adequate palliative care, she says, the worry is that assisted suicide “is not just a choice. It becomes a suggestion, which then becomes an expectation and that our vulnerable patients are at risk.”

Supporters of the bill say they too want more funding for hospices and are prepared for a debate about how and if such a commitment could be woven into the bill.

They also know that moral, religious and practical objections must be overcome if the momentous change they propose is to become law.