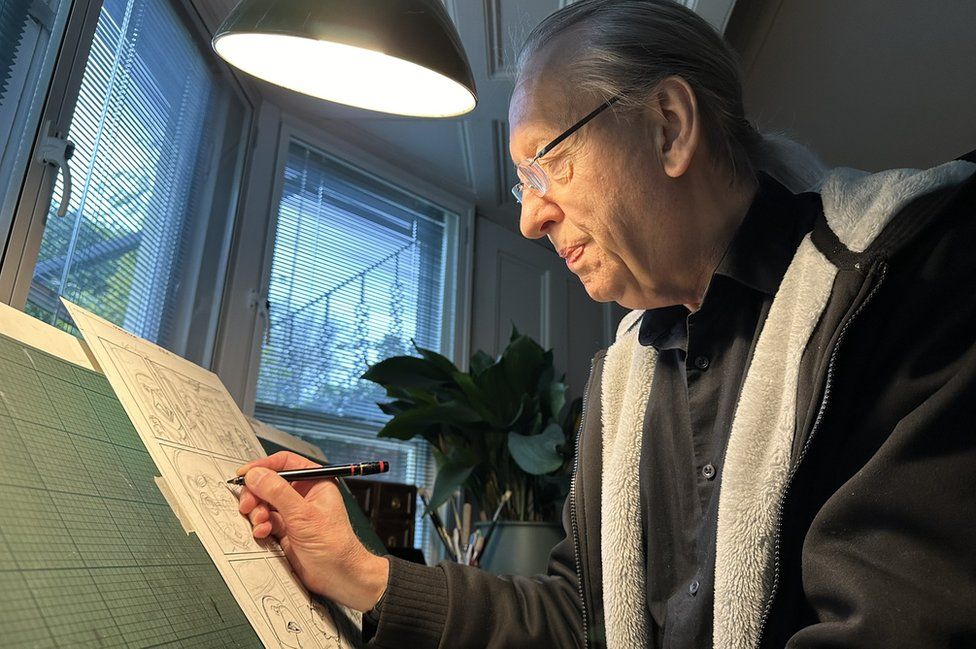

Bryan Talbot works in a studio in the basement of his Sunderland home

By Duncan Leatherdale

BBC News

British graphic novelist Bryan Talbot is set to be inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Awards Hall of Fame, the highest accolade for comic writers and artists from across the world. The BBC spent an afternoon with him in his studio.

Deep in the basement of a Victorian terrace in Sunderland there lurks a living legend.

Dressed all in black with his long silver hair tied back, Bryan Talbot certainly looks the part as he stands at a large drawing board in the semi-subterranean bay window.

His walls are lined with shelves of well-thumbed books, from his childhood comic collection to reference works on art and anthropology, Victoriana and zoology.

Two bookcases groan under the heft of his own extensive canon of works created over half a century.

Bryan Talbot’s books have been translated into multiple languages

Born in 1950s Wigan to a coal miner and hairdresser, Bryan’s love of comics began before he could even read.

The word-free visuals of nursery tales gave way to Rupert The Bear and Giles cartoons strips, before he fell deeply for the Beano and Dandy, first bought for him as he lay in a hospital bed after having his tonsils removed.

“They were just so anarchic”, he says of Dennis the Menace and the Bash Street Kids.

“Before that, comics were very respectful and genteel. Suddenly teachers, park keepers and even parents were the enemy.”

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Bryan Talbot drew this self-aggrandising portrait as part of a spoof biography in Heart of Empire

He started drawing his own comics aged about five and excelled in English and art at school.

He was supported in his ambitions by his mother, who would sketch out hairstyles for her customers, and his father who enjoyed water colouring.

Bryan was the first in his family to attend higher education, studying fine art and graphic design before finding work in the underground comics industry burgeoning in the 1960s and 70s.

It was a world of counter-culture, anti-establishment comics from the “hippy generation”, full of “sex, drugs, rock and roll” as well as “whimsy and surrealism”, Bryan recalls with obvious fondness.

“The important thing these writers did was reclaim comics as an adult medium,” he says.

Bryan is now a frequent collaborator with his wife Mary

But he always harboured a fantasy for something much more ambitious – a full novel told in comic form.

He tried to create a Lord of the Rings spin-off graphic novel when he was 17, but now says he lacked the skill to pull it off then.

He certainly had the talent and experience by 1981 when The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, his science-fiction tale of trans-dimensional wars and alterative histories, was published to wide acclaim.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Luther Arkwright is a trans-dimensional superhuman who tries to break down dictatorships and warlords

The nine-part story was released as a single volume at around the same time as Raymond Briggs’ When The Wind Blows and Posy Simmonds’ True Love.

“The three of them are the first British graphic novels,” Bryan says with a humble pride.

As an artist he has collaborated with numerous writers, including Neil Gaiman on the Sandman series, Pat Mills on 2000 AD’s Nemesis The Warlock and Alan Moore.

But while those “commercial” jobs paid the bills, Bryan’s passion was always for writing his own stories, including a two-parter for DC Comics in which Batman is all a figment of the imagination of a mentally unwell Bruce Wayne.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Bryan Talbot wrote and illustrated a two-part Batman story for DC Comics

“Making up the story is the fun bit, the best bit really,” Bryan says, adding: “Drawing it is the hard part.”

He always has a notebook in his pocket to jot down ideas, while piles of paper featuring sketches or hastily scribbled thoughts are scattered across his four-storey home.

He starts by writing a script, then begins the artwork from page one.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

The Tale of One Bad Rat follows a young woman’s escape from abuse into the solace and sanctuary of the Lake District

Bryan does two pages at a time, always conscious of the psychology of a comic reader to ensure the “reveals” in the plot are not prematurely spoiled. His fifth book in the Grandville series even had the final pages bound in black plastic so readers could not inadvertently glimpse the ending.

“People read the text, the speech bubbles or narration, in order, but their eyes are flicking all over both pages,” he says.

Bryan Talbot has written an array of graphic novels embracing a range of topics and styles

It takes about six days to draw two pages, with the work then inked and either painted with water colours or scanned in and digitally coloured.

The results have won him multiple awards and accolades.

The Tale Of One Bad Rat, Bryan’s Beatrix Potter-inspired story about child abuse, won the highly coveted Eisner award in 1996.

The Tale of One Bad Rat won Bryan an Eisner award in 1996

Two years later, he and his wife Mary moved to Sunderland on the windswept North East coast after she got a job as a lecturer at the city’s university.

The “big move”, as Bryan calls it, led directly to one his most creative and critically-lauded works – Alice In Sunderland.

“I think it was therapy for me and helped me cope with living somewhere new,” he says of the book, which details Sunderland’s history and its beguiling links to Lewis Carroll and Alice In Wonderland.

The book was a “hard sell” as it was unlike anything else on the market, combining artistic styles, history, biography and surrealism.

He drew the first 20 pages and showed them to a publisher but they could not grasp the whole concept.

Bryan Talbot does his art standing up

“I had all these ideas for it, the full 320 pages, and I could either shelve it and let it drain away or I could write it,” Bryan recalls. “I chose to write it.”

“Thankfully Mary had a good job so I could afford to take the time to do it.”

It took three years, at the end of which publisher Jonathan Cape agreed to take it on.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Alice in Sunderland is a genre-defying graphic novel about history, Sunderland, Lewis Carroll and story-telling

“It was one of my dreams to be published by a big publisher,” Bryan says, adding: “It did great, got great reviews.”

More glory came in 2012 when Dotter Of Her Father’s Eyes, his first collaboration with Mary, won the Costa biography award, becoming the first graphic novel to scoop the prize.

“I always said comics should not just sell to comic fans,” he says. “They should be something everybody reads and that book getting that award showed that.”

Image source, Getty Images

Bryan and Mary Talbot won a Costa award in 2012

Bryan and Mary’s has been a fruitful literary partnership, yielding five books and counting.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2018, using Lord Byron’s pen to sign his name while dressed appropriately in a billowing white shirt.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Bryan Talbot used Lord Byron’s pen to sign up as a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature

And later this year Bryan will lift his flight ban, self-imposed for environmental reasons, to travel to San Diego Comic Con where he will be inducted into the comics Hall of Fame, joining such illustrious names as Stan Lee, Tove Jansson and Jack Kirby.

“I was amazed and surprised,” Bryan says. “I had no idea I was up for it. It’s a huge honour.”

For now, down in his cellar studio, Bryan’s current focus is The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor, a prequel to his Grandville series which features anthropomorphised steampunk characters.

Bryan Talbot is currently working on The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor

Grandville is the alternative name for Paris in an early 19th Century where Britain is a part of the French empire.

The story follows the exploits of badger detective Archie LeBrock and his elegant rat sidekick as they tackle serial killers, cults and conspiracies.

As with much of Bryan’s work, in-jokes and references to art and comics burst out of almost every panel, while it’s aesthetic is turbo-charged Victorian.

Image source, Bryan Talbot

Grandville follows the exploits of badger detective Archie LeBrock

“The Victorian style is just a lot more interesting,” Bryan says. “The things they used to wear were amazing.

“Look at trains, for example. Nowadays they are like a box on wheels, but I can still remember when I was a child seeing the steam engines which were like these huge fire spitting monsters.”

Image source, Bryan Talbot

The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor is due out in 2025

With 110 of the 170 Hawksmoor pages completed, Bryan still has plenty of toil ahead.

The 72-year-old has to regularly stop to stretch his fingers and combat the arthritis creeping into his joints.

“I do suffer for my art,” he says with a laugh, before picking up his pen and heading back to the drawing board.

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.