BBC

BBC

A woman who was brutally attacked by a convicted murderer says proposals for the early release of hundreds of long-term prisoners have left her filled with fear.

Linda McDonald was battered with a dumb-bell by Robbie McIntosh when he was on home leave from a life sentence.

She believes other people will be at risk if the Scottish government frees prisoners sentenced to four years or more after two-thirds of their jail term.

The move is intended to address “critical” levels of overcrowding in Scotland’s jails.

It would apply to prisoners convicted of serious offences, including sexual and violent crimes.

Ministers insist public safety will be “an absolute priority” with prisoners subjected to an individualised risk assessment before release and supervised in the community afterwards.

Victims’ rights groups and social workers warn the system for monitoring prisoners freed on “non-parole licence” will struggle to cope without extra resources.

Robbie McIntosh was jailed for life in 2002 for stabbing civil servant Anne Nicoll to death when he was 15 years old.

Fifteen years later, he was being prepared for possible parole when he attacked Linda McDonald in woods on the outskirts of Dundee.

McIntosh fled after dog walkers heard Mrs McDonald’s screams. She suffered multiple injuries including two skull fractures.

The prospect of long-term inmates being freed early appals Mrs McDonald, who is backing concerns voiced by Victim Support Scotland.

“If this proposal goes ahead, we’re opening up the floodgates,” she said.

“The minute I heard ‘early release of long term prisoners’ it just filled me full of fear.

“Short-term offenders, definitely, I agree with that 100%.

“But we’re talking about people who have committed manslaughter, attempted murder, paedophiles. It’s just horrifying.”

The attack on Mrs McDonald led to McIntosh receiving an order for lifelong restriction, a sentence which involves a jail term followed by supervision until he dies.

The Scottish government’s proposals will not cover people serving life, orders for lifelong restriction, or extended sentences which involve custody and supervision in the community.

In a briefing document, the government said if the plan had been enacted on 31 May this year, it would have resulted in the immediate release of around 320 prisoners.

The change would apply “retroactively” to people sentenced after 1 February 2016, the last time the rules on release were altered, and anyone coming before the courts in the future.

‘Trust in the justice system is at an all-time low’

Victim Support Scotland chief executive Kate Wallace described the six-week public consultation on the proposals as “very rushed.”

“Trust and confidence in the justice system is at an all-time low in Scotland,” she said.

“Dealing with the prison population by letting people out early is not the answer.

“We need to look at the root causes and we need a serious look at rehabilitation.”

The Scottish Association of Social Work has warned the profession is under-staffed, with a 6% vacancy rate among justice social workers

The association’s national director Alison Bavidge said: “It will be a significant challenge. That cannot be under-estimated. The sector is already stretched excessively.”

Asked if there was a danger former prisoners would reoffend if the right support wasn’t in place, she replied: “Bluntly, yes.”

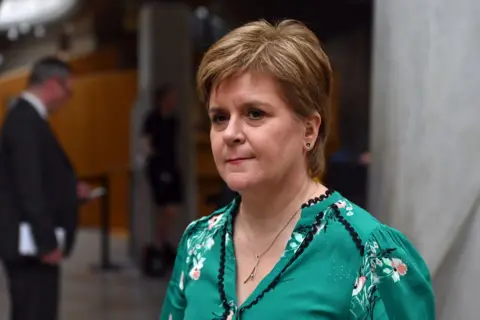

Long-term prisoners were released after two-thirds of their sentence until February 2016, when the rules were changed under legislation introduced by Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP-run government.

The Prisoners (Control of Release) (Scotland) Act stipulated that long-term prisoners not granted parole should be freed when they had six months left to serve.

Getty Images

Getty Images

At the time, the then First Minister Ms Sturgeon said: “If you are a long-term prisoner… the expectation should be that you serve all of your sentence in jail.”

SNP ministers now want to revert to the old system as they wrestle with a sharp increase in the prison population.

The operating capacity of Scotland’s jails is 8,007 but in May it was 8,348. According to the government, the latest modelling suggests that by October, the population could be anywhere between 7,650 and 9,150.

One of the reasons is an increase in convictions of sex offenders and members of serious organised crime groups.

The courts are getting through the backlog caused by Covid, resulting in more people being sent to jail. At the same time, a huge number are on remand awaiting trial or sentence.

Around 500 short-term prisoners are already in the process of being released to ease pressure on the jails.

When the consultation on the early release of long-term prisoners was announced, the Scottish government argued it would provide “a more managed return to the community” and would be “a proportionate way to reduce the pressure on the prison estate.”

The justice secretary Angela Constance said: “Release under licence conditions means strict community supervision and specific support in place, informed by robust individual risk assessments of prisoners.

“These measures would be introduced through legislation, requiring debate and the approval of parliament.”