Getty Images

Getty Images

The Budget will only “temporarily boost” the economy, according to official forecasts, throwing into question the government’s promises to reboot growth.

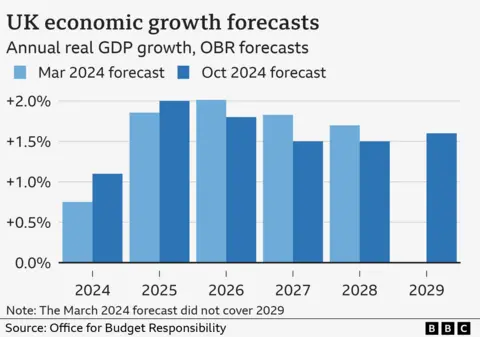

The pace of growth will peak next year at 2% before falling back to around 1.5% later in the parliament, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) said.

The government has pinned its reputation on delivering growth, arguing that a new approach to investment would underpin a better economic performance and “more pounds in people’s pockets”.

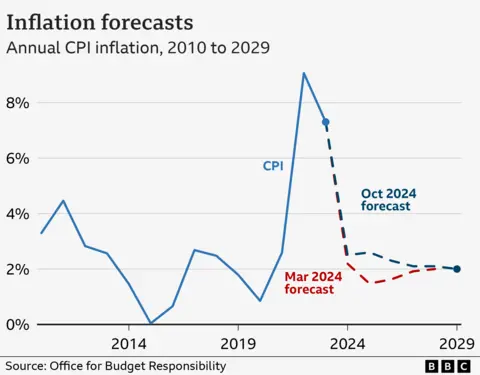

But the OBR said in the short term the Budget would push up inflation and interest rates, with a knock-on effect on growth.

Overall that would leave the size of the economy “largely unchanged in five years” compared to its previous growth forecast, the OBR said.

In her speech, Chancellor Rachel Reeves said: “Every Budget I deliver will be focused on our mission to grow the economy.”

She also promised “an end to short-termism”.

The package of policies includes tax increases to the tune of £41bn a year by the end of the parliament to finance more spending on public services.

“The OBR pointed to a short-term sugar rush, as a result of the debt-financed spending splurge, but that turns into a modestly negative impact by the end of the parliament,” Paul Johnson, head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent economics think tank, said in a note.

The OBR said in the longer term investment, planning reform and greater economic stability should help to boost growth, “in a sustainable way” Mr Johnson said, but not until 2032.

It is hard it to make precise predictions several years ahead, and economic forecasts are regularly updated.

The combination of stronger growth early in the parliament, followed by weaker growth in later years, suggests the cumulative impact will be small.

In total the economy is set to grow by nearly 8.2% in total by 2028. In March it was forecast to grow by nearly 8.5%.

However, Mr Johnson described the growth forecast as “pretty disappointing stuff”.

Measures in the Budget would increase demand this year and next year, which was likely to keep inflation and interest rates higher, resulting in slower growth in later years, he told the BBC.

The OBR expects inflation to remain slightly above the Bank of England’s 2% target until 2029.

How much the economy grows is a key factor limiting what the government will be able to do over the course of the parliament.

If growth is strong, tax revenues are likely to increase, meaning there is more to spend on public services, or on reducing taxes, and to pay the interest on government borrowing. If growth is weak, the government is likely to have to cut back on what it would like to do.

Reeves said while there would be no return to austerity, there would “still be hard decisions to come”.

But she said the OBR believed Labour’s plans would have a positive impact on the “supply capacity of the economy” or its ability to grow.

The government bases its policy plans on the forecast of the OBR. However, economic forecasting is not an exact science.

Predictions can be affected by a huge range of factors including geopolitical risk, global energy prices, and events in the world’s other large economies. Small changes in any of these factors can have an impact on the path of UK growth.

Reeves said she would “catalyse £70bn of investment” in the UK through a new National Wealth fund, transform planning rules to “get Britain building”.

She said she would work with devolved governments in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as well as regional mayors, to boost local and regional growth plans.