By Philip Sim & Anthony Reuben

BBC News

Nicola Sturgeon is preparing to leave office after more than eight years as Scotland’s first minister, with MSPs giving her a standing ovation on Thursday as she made her final speech in the Scottish Parliament before standing down.

Ms Sturgeon has spoken of her pride at what she has accomplished – pointing to Scotland’s ambitious climate change targets, record funding for the NHS and her remarkable eight election wins.

But her political opponents have claimed that Scotland’s schools and hospitals are in a worse state now when she took over.

We dove into the statistics to try to draw some hard conclusions about what Ms Sturgeon’s record time in office has meant for Scotland’s economy, politics and climate change credentials, as well as its health and education systems.

Electoral juggernaut

Nicola Sturgeon’s term in office has seen the SNP all but wipe its political rivals off the electoral map.

The party had already chased down and overtaken Labour at Holyrood, seizing power in 2007 and securing an unprecedented majority in 2011 with Alex Salmond at the helm.

But within months of Ms Sturgeon taking charge, the SNP also enjoyed remarkable general election.

The party won all but three of the 59 seats in Scotland in the 2015 election, gaining 40 from Labour and 10 from the Liberal Democrats.

Labour’s collapse was so comprehensive that the Conservatives achieved what once seemed unthinkable by replacing them as the second party in Scotland right through to the local elections in 2022 – but the Tories did not come close to catching the SNP.

Ms Sturgeon’s run continued with thumping Holyrood victories in 2016 and 2021, as well as another big UK win in 2019.

The fact the 2017 general election came as a setback – when the SNP won “only” 35 seats – only underlines how total the SNP’s domination of electoral politics in Scotland has become in recent years.

Drug deaths

Scotland’s record toll of drug-related deaths is perhaps the country’s grimmest statistic of recent years.

It has by far the worst death rate recorded by any country in Europe, and was 3.7 times higher than the UK as a whole when the last comparable figures were available.

A slew of policy responses have been tried – including working groups, action teams and a dedicated minister for the issue – without managing to make any significant reduction to the figures.

After years of alarming acceleration, there was a slight fall in the number of deaths in the most recent figures – but the death toll from drugs continues to be far higher than it was before Ms Sturgeon took office.

Further attempts to turn the tide are in the pipeline, with the government’s top lawyer reassessing whether safe consumption rooms can be set up to help prevent overdoses.

Progressive taxation

A new Scottish income tax regime was set up on Ms Sturgeon’s watch, and in the most recent budget her government doubled down on its approach of raising rates at the top end.

The five-band system introduced in 2016 has resulted in higher earners paying more than those elsewhere in the UK, and those on the lowest incomes paying slightly less.

Ministers have always been careful to strike the balance so that the majority of Scots ratepayers – currently 52% of them – pay less in tax than they would if they lived south of the border, to the tune of £22 a year.

The differences are much starker at the top end. Someone earning £50,000 a year in Scotland will see an extra £1,552 go to the taxman compared to the UK regime, and those on £100,000 pay an extra £2,606.

Questions have been raised about the amount of extra cash this actually raises once behavioural changes are factored in, and whether it could impact on productivity.

But the government views it as an important principle in the social contract – that those who earn more should pay a bit more in order to help build a “fairer society”.

Redistributing wealth

The aim of the changes to the income tax system has been to shift wealth from the better off to those on lower incomes.

Another major part of this agenda has been the creation of Social Security Scotland, a new welfare agency set up to deliver benefits devolved to Holyrood in the wake of the 2014 referendum.

These are often designed to be more generous than the UK equivalents being replaced, and welfare spending is projected to rise considerably in the coming years – one of the only areas of the budget forecast to actually go up.

This chart – using figures from the Institute for Fiscal Studies – incorporates a range of different measures including the income tax system, benefits like the Scottish Child Payment and Best Start Grant, and the action taken to mitigate UK benefit capping moves like the “bedroom tax”.

It shows that – at least in theory – the poorest households in Scotland have more disposable income than their counterparts in England and Wales, while better-off ones have comparatively less.

It doesn’t adjust for changes in behaviour or cover the sharply varying rates of council tax in different areas, but it does illustrate the Scottish government’s broader goal of redistributing wealth across society.

Educational attainment

It was famously Ms Sturgeon’s “number one priority” and one she wished to be judged on – closing the gap in educational outcomes between school pupils from better off and more deprived areas.

It was a bold policy promise, but one which has been thrown back in her face repeatedly by opponents in the years since, because the gap has stubbornly refused to close.

The government points to the Covid pandemic as a major factor, by having a disproportionate impact on learning for children from more deprived backgrounds.

And it might well be the case that some of the efforts to tackle child poverty and expand childcare provision will, in time, have a positive impact on educational attainment.

But education reforms have stuttered throughout Ms Sturgeon’s time in office, with a flagship piece of legislation shelved in 2018 and work to replace the qualifications and schools bodies ongoing.

Climate change

Ms Sturgeon was one of the first politicians to formally announce a “climate emergency” back in 2019.

She also brought the Scottish Greens into government, met Greta Thunberg at COP26 as the climate conference kicked off in Glasgow in 2021, and has called for a “just transition” away from North Sea oil and gas.

This was a major shift for a leader who only a few years earlier had committed to “maximise economic recovery from the North Sea” and who leads a party whose most famous slogan was once “It’s Scotland’s oil”.

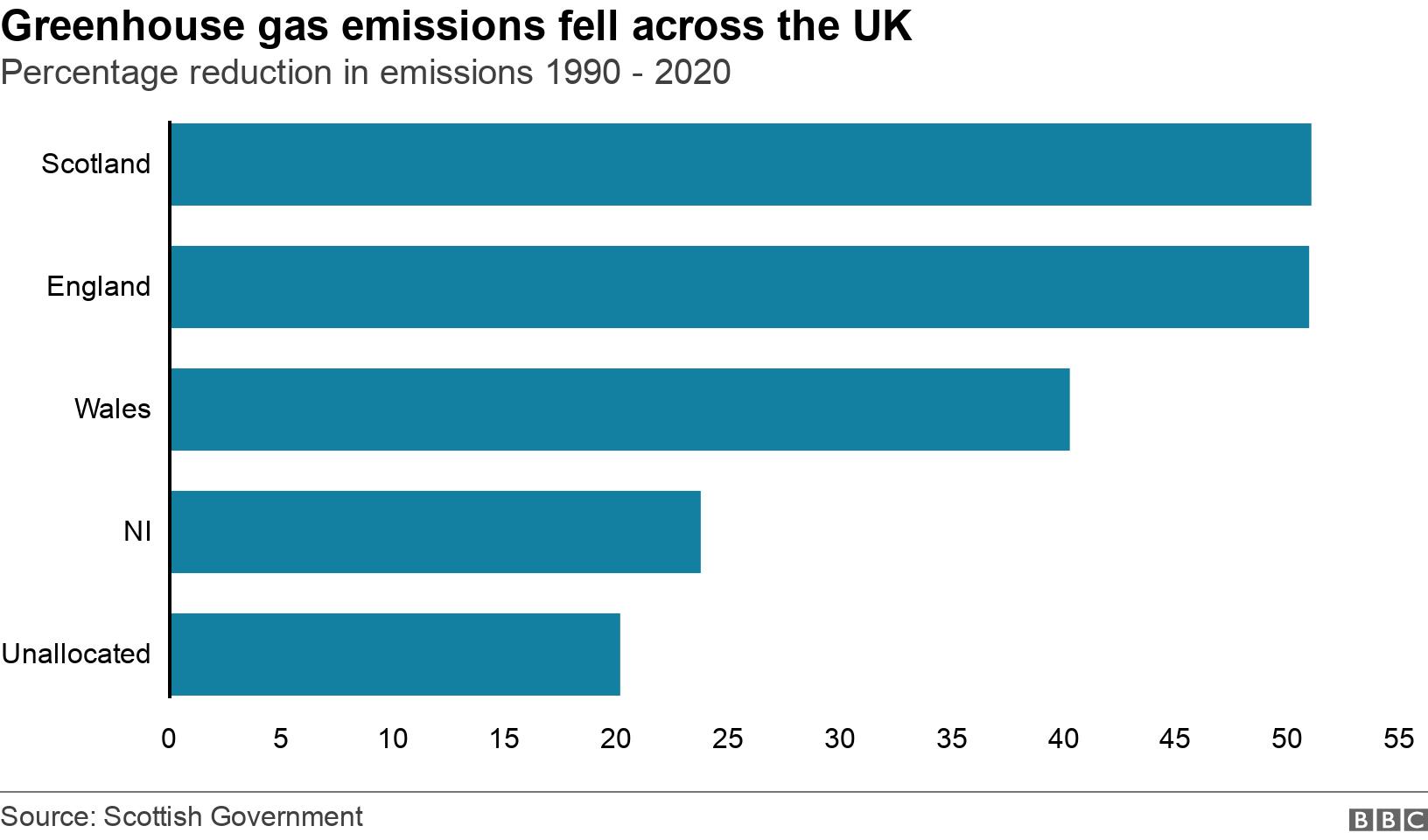

Under Ms Sturgeon, the Scottish government has set ambitious targets for cutting carbon emissions to “net zero” by 2045. However it has not always lived up to those lofty aims, with interim goals missed.

And the Committee on Climate Change has warned that Scotland has now lost its lead over other parts of the UK, warning that progress on cutting emissions had “largely stalled”.

Health services

The NHS has just limped though its most difficult winter ever, having already been rocked to its foundations by the Covid pandemic.

But lockdown was actually the only time the government’s waiting times target – for 95% of patients to be seen within four hours – has actually been hit in recent years.

Hospital delays became a weekly fixture of questions to the first minister from opposition leaders, with Ms Sturgeon frequently confronted with case studies of patients who had been left waiting for hours for an ambulance to arrive or in accident and emergency units.

While she would always admit that these stories were unacceptable, she would also highlight that the challenges are not unique to Scotland.

However direct comparison is extremely difficult – for all that politicians regularly try – because of the differences in how A&Es are categorised in different parts of the country, and how the figures are compiled.

Independence

Ms Sturgeon entered politics largely because she wanted Scotland to be independent, and entered Bute House off the back of a referendum campaign which fell short of achieving that goal.

Did she move the dial on the issue which has driven her politics since her teenage years?

Polls suggest that the country remains every bit as divided over the issue as it was on the day she took over from Alex Salmond.

There was a bounce for No following 2017’s post-Brexit election, and a bump for Yes during the Covid pandemic – which is often hailed as Ms Sturgeon’s best leadership moment.

Her supporters argue that being within margin-of-error touching distance of victory is a pretty good starting point for a new campaign, given the Yes movement started the previous one miles behind.

But she is leaving behind a party divided on how to pursue independence, with the UK government continuing to refuse to allow a second referendum and the Supreme Court having rejected the notion of Holyrood holding a vote on its own.

A planned SNP conference to set a new strategy was postponed following Ms Sturgeon’s resignation announcement, and it will be down to her successor to try to chart a course towards a goal which ultimately eluded her.