BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson

‘Thomas’ – not his real name – was 13 years old when he began his first stint in prison.

Following the sudden death of his father, he had robbed a shop in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT). He was detained for a week but, within a month, he was back in custody for another burglary.

Five years on, the Aboriginal teenager has spent far more of that time inside prison than out.

“It’s hard changing,” Thomas tells me. “[Breaking the law] is something that you grow up your whole life doing – it’s hard to [stop] the habit.”

His story – a revolving door of crime, arrest and release – is not an isolated one in the Northern Territory.

For many, over the years the crimes get more serious, the sentences longer and the time spent between prison spells ever briefer.

The Northern Territory is the part of Australia with the highest rate of incarceration: more than 1,100 per 100,000 people are behind bars, which is greater than five times the national average.

It’s also more than twice the rate of the US, which is the country with the highest number of people behind bars.

But the issue of jailing children in particular has been thrust into the spotlight here, after the territory’s new government controversially lowered the age of criminal responsibility from 12 back to 10.

The move, which defies a UN recommendation, means potentially locking up even more young people.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson

It’s not just an issue of incarceration. It’s one of inequalities too.

While around 30% of the Northern Territory’s population is Aboriginal, almost all young people locked up here are Indigenous.

So, Aboriginal communities are by far the most affected by the new laws.

The Country Liberal Party (CLP) government says it has a mandate after campaigning to keep Territorians safe. It helped the party claim a landslide victory in August’s elections.

Among those voting for the CLP was Sunil Kumar.

The owner of two Indian restaurants in Darwin, he’s had five or six break-ins this past year and wants politicians to take more action.

“It’s young kids doing [it] most of the time – [they] think it’s fun,” explains Mr Kumar.

He says he’s improved his locks, put in cameras and even offered soft drinks to kids loitering outside in a bid to win them over.

“How come they are out and parents don’t know?” he says. “There should be a punishment for the parents.”

But while the political rhetoric around crime is powerful, critics say it actually has little to do with real numbers.

Youth offender rates have risen since Covid. Last year, there was a 4% rise nationally.

But the rates are about half of what they were 15 years ago in the Northern Territory, Australian Bureau of Statistics figures show.

Politicians, though, are playing to residents’ fears.

As well as lowering the age of criminal responsibility, they have also introduced tougher bail legislation known as Declan’s Law, after Declan Laverty, a 20-year-old who was fatally stabbed last year by someone on bail for a previous alleged assault.

“I never want another family to experience what we have,” said his mother Samara Laverty.

“The passing of this legislation is a turning point for the Territory, which will become a safer, happier, and more peaceful place.”

‘10 year olds still have baby teeth’

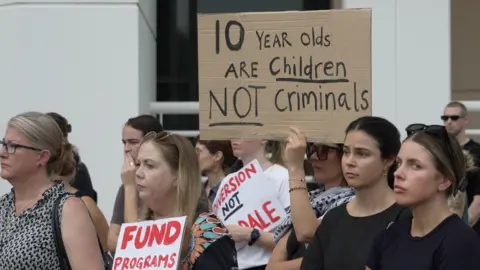

On the day the laws started to be debated in Darwin last month, a small crowd of demonstrators stood outside parliament in a last-ditch effort to turn the political tide.

One woman held up a placard that read: ’10 year olds still have baby teeth’. Another asked: ‘What if it was your child?’

“Our young people in Don Dale need to have opportunity for hope,” said Aboriginal elder, Aunty Barb Nasir, addressing the demonstrators.

She was referring to a notorious youth detention centre just outside Darwin, where evidence of abuse – including video of a child wearing a spit hood and shackled to a chair – outraged many in Australia and led to a royal commission inquiry.

“We need to always stand for them because they are lost in there,” Aunty Barb said.

Kat McNamara, an independent politician who opposed the bill, told the crowd: “The idea that in order to support a 10-year-old you have to criminalise them is irrational, ineffective and morally bankrupt.”

After a ripple of applause, she added: “We are not going to stand for it.”

But with a large majority in parliament, the CLP easily managed to pass the laws.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson

Lowering the age of criminal responsibility undid legislation passed just last year that had briefly lifted the threshold to 12.

And while other Australian states and territories have been under pressure to raise the age from 10 to 14, for now it is once again 10 across the country, with the exception of the Australian Capital Territory.

Australia is not alone – in England and Wales, for instance, it is also set at 10.

But in comparison, the majority of European Union members make it 14, in line with UN recommendations.

The Northern Territory’s Chief Minister, Lia Finocchiaro, argues that by lowering the age of criminal responsibility, authorities can “intervene early and address the root causes of crime”.

“We have this obligation to the child who has been let down in a number of ways, over a long period of time,” she said last month.

“And we have [an obligation to] the people who just want to be safe, people who don’t want to live in fear any more.”

But for people like Thomas, now 18, prison didn’t fix anything. His crimes just got worse, and his time inside increased.

He says he finds prison oddly comforting. It’s not that he likes it, but with custody comes familiarity.

“Most of my family has been in and out of jail. I felt like I was at home because all the boys took care of me.”

His two younger brothers are also stuck in a similar cycle. At one point, their mother was catching a bus to visit all three in prison every week.

Thomas still wears an ankle bracelet issued by authorities but he has been out of prison for nearly three months now – his longest spell of freedom since becoming a teenager.

He’s been helped by Brother 2 Another – an Aboriginal-led project that mentors and supports First Nations children caught up in the justice system.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson

“Locking these kids up is just a reactive way to go about it,” says Darren Damaso, a youth leader for Brother 2 Another.

“There needs to be more rehabilitative support services, more funding towards Aboriginal-led programmes, because they actually understand what’s happening for these families. And then we’re going to slowly start to see change. But if it’s just a ‘lock them up’ default action, it’s not going to work.”

Mr Damaso is from the Larrakia Aboriginal people, the ancestral owners of the region of Darwin, and he also has connections to the Yanuwa and Malak Malak people.

His organisation brings young people to a refashioned unit on an industrial estate on the outskirts of Darwin, providing a space to relax, a sensory room and a gym.

Brother 2 Another also works in schools and tries to help young people find work – opportunities that many who’ve been involved with police and prisons struggle to engage with.

“It’s a self-perpetuating cycle,” says John Lawrence, a Scottish criminal barrister who’s been based in Darwin for more than three decades.

He’s represented many young people and argues more money needs to go into schooling than the prison system, to prevent incarceration in the first place.

Aboriginal people “have no voice, and so they suffer great injustice and harm”, says Mr Lawrence.

“The fact that this can happen reveals very graphically and obviously how racist this country is.”

A national debate

The tough talk on crime isn’t particular to politics in the Northern Territory.

In Queensland’s recent elections, the winning campaign by the Liberal National Party played heavily on its slogan: “Adult crime, adult time.”

In a recent report by the Australian Human Rights Commission, Anne Hollonds, the National Children’s Commissioner, argued that by criminalising vulnerable children – many of them First Nations children – the country is creating “one of Australia’s most urgent human rights challenges”.

“The systems that are meant to help them, including health, education and social services, are not fit-for-purpose and these children are falling through the gaps,” she said.

“We cannot police our way out of this problem, and the evidence shows that locking up children does not make the community safer.”

Which is why there’s a growing push to fund early intervention through education, not incarceration, and trying to reduce marginalisation and disadvantage in the first place.

“What are the cultural strengths of people? What are the community strengths of people? We are building on that,” says Erin Reilly, a regional director for Children’s Ground.

Her organisation works with communities and schools on their ancestral lands, learning about foods and medicines from the bush and about the Aboriginal ‘kinship’ system – how people fit in with their community and family.

“We centre Indigenous world views and Indigenous values and we work in a way that works for Aboriginal people,” explains Ms Reilly.

“We know that the education system and health systems don’t work for our people.”

For Thomas, life on the inside was hard, involving weeks at a time spent in isolation. But on the outside, he says, there’s little understanding of the circumstances he’s lived through.

“I felt like no one cared. Nobody wanted to listen,” he says.

He points out the bite marks on his forearms and adds: “So, I hurt myself all the time – see the scars here?”

Additional reporting by Simon Atkinson