BBC

BBC

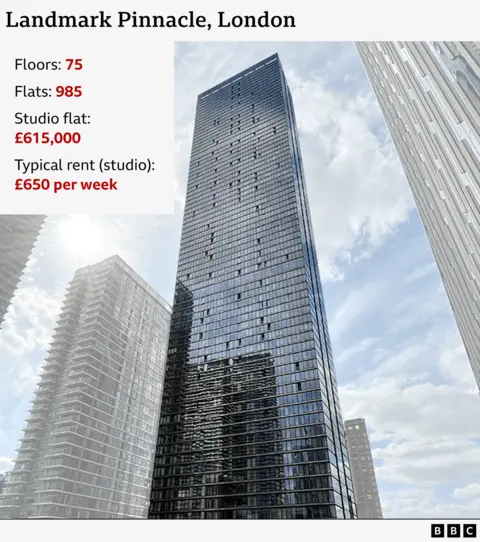

Looking up at the glimmering Landmark Pinnacle on London’s Isle of Dogs, it’s hard to crane your neck back far enough to see right to the top.

Completed in 2020, it is the tallest mainly residential building in Europe, soaring 784ft (239m) and 75 floors into the sky. It has a gym, roof terrace and designated pilates area.

Inside, one of three concierges ask, without smiling, who I’m visiting, and I’m shown to one of the lifts. Apparently they don’t usually let you in without a name.

Seven years ago, the catastrophic fire at Grenfell Tower led to changes in how high-rises should be designed to keep residents safe during a blaze.

But problems persist in existing blocks.

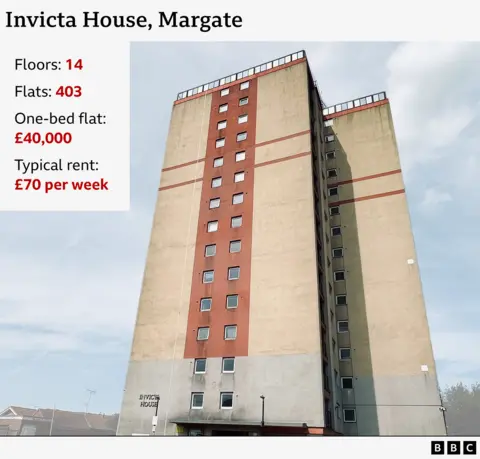

I’ve visited the Landmark Pinnacle as well as Invicta House, a council-owned block on an estate just outside Margate. While there are significant differences, concerns have crept up at both.

Invicta House, built in the 1960s on the Isle of Thanet, in East Kent, is a mere 14 floors and stands austere among mainly low-rise housing.

There are no door staff here, and I tailgated some residents through a starkly decorated lobby.

Both towers have stunning views – of the Kent coast and the looping Thames respectively. But there is no denying the economic gulf between those on minimum wage and benefits at Invicta House, and the city workers and well-off foreign students living at the Landmark Pinnacle.

You could buy 15 one-bed flats at Invicta House for the same price as a studio apartment just over 70-miles away, in the Landmark Pinnacle in Canary Wharf.

Invicta resident David Bond is a council tenant, and proud of his military service in Cold War Germany, signified by two model tanks carefully displayed on his sideboard.

The block is a place where “people keep themselves to themselves”, he says, admitting he prefers it this way.

There are drug-users, drinkers and prison-leavers among his neighbours, and “too many dogs”, he complains. The overpowering smell in the building’s lifts, several residents explain, is dog urine.

In spite of their differences, something the residents of both Invicta House and Landmark Pinnacle have in common is their complete reliance on lifts.

On a high floor at Invicta, John – who asked me not to use his real name – says the two lifts in the building, which serve odd and even floors, constantly break down. Engineers use parts from one to fix the other.

John has a number of medical conditions and walking up the stairs just isn’t an option.

“You fear going out in case you get back and find the lifts aren’t working,” he says. Sometimes he has had to stay with friends instead of going home.

At the Landmark Pinnacle building a lift takes me to the 13th floor in a matter of seconds.

Two years ago, Guy Benson, a young city worker and part time Liberal Democrat activist, bought 25% of the lease for his £700,000 flat under a shared ownership scheme.

Landmark Pinnacle has also had lifts out of action, and one isn’t working today – but Guy puts that down to teething problems.

“It’s like building a massive machine and you don’t get everything right the first time,” he says, adding that having more lifts would probably be helpful. The building already has seven.

Using the stairs would be daunting. Looking down the stairwell from the 75th floor the landings seem to stretch into infinity.

What happened at Grenfell Tower in 2017, when a devastating fire destroyed the building and 72 people lost their lives, raised major questions about the design and operation of high-rise towers, and the response of their residents in an emergency. There has been much discussion about staircases.

As a result of Grenfell, from 2026 all new buildings over 59ft (18m) must have two staircases – one for firefighters to go up to tackle fires, the other for residents to come down in a “simultaneous evacuation”. Lifts aren’t recommended in a fire.

Unsurprisingly, Invicta House, built more than five decades ago, has a single staircase.

But the state-of-the-art Landmark Pinnacle, completed in the wake of a building safety crisis, was also designed to have only one. Adding another staircase to a building already under construction when the law changed wasn’t practical, it seems, but two could have been part of the original design.

Both towers have had recent fires.

In 2021, a candle set light to a flat at the Landmark Pinnacle on a floor in the 30s. Some residents couldn’t hear a fire alarm and like those at Grenfell had to decide to stay put or get out.

The building has a “stay put” policy because it is designed so fires can’t spread between flats. Alarms don’t even go off on unaffected floors.

Yet in Facebook messages shown to the BBC, residents – some of whom could smell burning and see fire trucks gathering outside – appear confused about what to do. Grenfell was doubtless on everyone’s mind.

The fire was swiftly put out, with the help of the in-built sprinkler system.

And should there be another fire, Guy Benson has faith that the way this building has been designed will keep him safe.

“I don’t feel at risk at all,” he says.

At Invicta House there has been a spate of fires, apparently started deliberately, in chutes used to send rubbish to the ground floor. Jane, one of the residents, describes opening her door to a thick wall of smoke.

But seven years after Grenfell – and in contrast to Landmark Pinnacle – Invicta House is still a fire risk. In particular, the combustible polystyrene insulation on its walls. Planning permission to remove it was granted in March, but the work, predicted to start in April this year, still hasn’t.

The rubbish chutes have been modified to deter arsonists, and a trained fire warden patrols around the clock. Like Grenfell, there’s a risk that any fire would spread throughout this building, so residents are advised to “get out” if the alarms go off – and that means taking the stairs.

“I can’t get down the stairs,” says Jane, “I’m on crutches.” Last time the fire alarm went off, she says she just shut the door.

On another floor an empty wheelchair sits on a landing, a symbol of the vulnerability of many in the building.

The residents mainly rent, so aren’t stuck with a flat they can’t sell like many around the country – but most have no other housing options.

John – who moved here after a fire in his previous accommodation – pays £70 a week rent.

“I’m lucky to have a place that I can afford,” he says, “and when I close the door I’ve closed the outside world out.”

The difference in fire safety experiences between tower block residents at opposite ends of the economic spectrum greatly concerns Dr Barbara Lane, one of the Grenfell Tower public inquiry’s expert witnesses, who argues that removing this “inequity” should be a priority.

To do so would require a comprehensive examination of the existing fire risks of older buildings, proactively removing them, and thinking more carefully about how vulnerable people will get out – concentrating as much on “disabled egress” as disabled access.

For those tenants who need extra help, Thanet District Council offers a Personal Emergency Evacuation Plan. This is already a recommendation of the Grenfell Tower public inquiry, and the government has recently announced that offering an evacuation plan is to become a legal requirement for building owners.

The residents of the Landmark Pinnacle and Invicta House have something else in common – a degree of powerlessness.

They all live in a building they do not own. The tenants in Margate rely on Thanet District Council. The leaseholders in east London, on their building manager.

On the 13th floor of the Landmark Pinnacle, Guy Benson studies a spreadsheet at a window which looks out over an expanse of south London.

He is worried about his growing energy bills and service charges – despite not paying extra for access to the Landmark’s gym and private cinema. He agrees there is a power imbalance.

“You’re never able to negate it, you do have less control, ” he says. “Being able to understand the system and the levers you have to pull is absolutely an advantage – but you shouldn’t have to become a property law expert.”

Another resident at the Landmark Pinnacle, Alex – not his real name – echoes the view of many leaseholders in England and Wales of their landlords.

“We feel like we are getting ripped off. There’s nothing we can do. It’s like paying taxes but without being able to get rid of your government.”

Alex wants the Landmark Pinnacle’s residents to exercise their Right to Manage. He has asked the building managers, Rendall & Rittner, to contact the owners of each flat to let them know about his plan – but says they have refused. Alex reckons the management company is protecting its own interests. However, Rendall & Rittner, told the BBC it has not received any requests from residents about Right to Manage.

The government plans further reforms to leasehold laws building on changes introduced by the Conservatives.

In Kent, David Bond, who has a sea view from his balcony, says council officials “build a big wall” when he raises concerns about the lifts and delays to building safety work. He doesn’t blame the housing officers he deals with, but says they are “struggling with regulations”.

“People don’t take us seriously,” he says. “We should stop paying the rent and then it would become serious.”

A spokesperson for Rendall & Rittner, the management company that runs Landmark Pinnacle, told the BBC the building’s stay put policy is communicated to all residents and leaseholders regularly. A requirement set by London Fire Brigade, it “forms part of the overall fire strategy and Fire Risk Assessment that is reviewed by specialist consultants to ensure the highest level of compliance”.

Rendall & Rittner said it “endeavours to keep service charges as reasonable as possible, however new requirements brought in by the Building Safety Act, together with the cost of living and energy crisis, have contributed to increasing costs”, while highlighting that although one of the Landmark Pinnacle’s seven lifts is currently undergoing general maintenance this is at no additional cost to leaseholders.

A spokesperon for Thanet District Council told the BBC the safety of its residents is “paramount”, and that they “work closely with the Kent Fire and Rescue Service”.

The statement continues: “Work at Invicta House, which includes the replacement of the external wall insulation, is now planned to start in May 2025.

“In 2019, the fire protection was upgraded in the building’s stairwells, all the fire doors were replaced and the fire alarm system was upgraded. We moved from a ‘stay put policy’ to ‘simultaneous evacuation’ in July 2021. All residents must evacuate the block if they hear the fire alarm.”

Living at height isn’t for everyone, but those I spoke to said, on balance, they liked looking down on the rest of us.

“I wouldn’t have chosen to live here,” says John, at Invicta House, “but I know more of my neighbours here than I’ve ever known living elsewhere.”

For Alex, at Landmark Pinnacle, high-rise living has many benefits.

“We can’t all live in detached houses,” he says, arguing that on an island short on space, building upwards was the most sustainable option.

“It’s good to have people around you – it makes you more open-minded.”