‘I still haven’t spoken to my mum about losing my baby’

Getty Images

Getty Images

Miscarriage rates among black women have been more than 40% higher than for white, while stillbirth rates for black and Asian babies have been “exceptionally high”.

“Evidence tells us that black and Asian babies are more likely to be stillborn or die as newborns compared with white babies,” said Jen Coates, a director at baby loss charity Sands.

She said urgent action was needed to end the inequality.

Baby Loss Week, which runs until Tuesday, aims to remind grieving parents and families they are not alone.

A group of black women from Essex and London-based support group Ebony Bonds have been using their experiences to help other families.

‘It’s like we are a burden on the service’

Rachel Burrell

Rachel Burrell

British-Jamaican mother Rachel Burrell said she had been “over the moon” to discover she was pregnant with her first daughter, Rhema.

But after nine hours of labour and a failed epidural, she walked back through the hospital pregnancy suite “with an empty car seat and no daughter”.

Rhema had been stillborn.

Ms Burrell, 40, who lives in south London and works as a human resources director in Witham, Essex, said throughout her 2012 pregnancy, her concerns were often met with eye-rolls and a cold reception.

“I had some difficulties with the NHS and how I was treated,” she said.

- If you have been affected by the issues in this story, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line

When she was pregnant again, two years later, the same consultant she had seen previously told her to “cut her losses” and terminate her now-healthy child, she said.

“We have multiple stories of care negligence and we have to address that something is going wrong with that care pathway,” she said.

“It’s like we are a burden on the service and we have to be told at a really early stage of the pregnancy.”

She said she found support in baby loss groups run by charities, despite often being the only black woman in the room.

“You cannot be at a table talking about baby loss, [from] which we are disproportionately affected… and not have anybody discussing that inequality,” she said.

“When you walk into a support group as a black woman and you are at your most vulnerable, and if you do not see anyone who looks like you or facilitating you, the likelihood is that you’re not going to stay.”

She said black and minority ethnic women should feel represented.

“It’s not about excluding white people – it’s about including black people,” she said.

“We just want to have babies that live, too.”

‘I was too embarrassed to tackle the issue head-on’

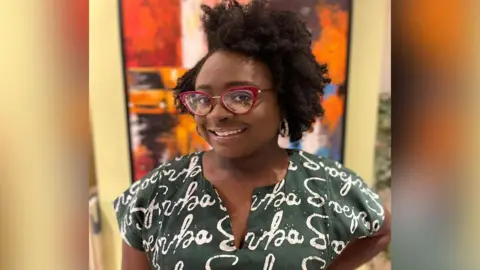

Seyi B

Seyi B

Seyi, 35, lost her second daughter, Iyanu, in 2021 after a placenta abruption at 36 weeks.

“There are no words you can say to someone who has lost their child,” she said.

A project manager from Romford, east London, she said she struggled with the stigma of losing her child within her Nigerian culture.

“To this day, I haven’t spoken to my mum about it,” she said.

“My mum doesn’t know my daughter’s name, because she is of that ‘old school’ generation where you don’t name the child.”

She said her mother told her: “The child is gone – God is going to bless you with another child.”

She explained: “I had to offer a lot of grace and understanding, because they dealt with things by burying their trauma.

“I was always going to church and then after it happened, I didn’t. I just stopped.

“I was too embarrassed to go to church to even face people. I was too embarrassed to tackle the issue head-on.”

A few years later, she gave birth to a son – a “rainbow baby” – but said while people expected her to move on, she did not want to.

Determined to honour Iyanu, today she proudly calls herself a mother of three.

“I had to be strong to fight for my child, but when you’re grieving, you want to be weak and you want to cry and you want to be vulnerable,” she said.

“People would say to me, ‘Be strong’, and I’d be like, ‘No – I want to be weak right now.’

“[Being strong] is ingrained in us. We’ve seen our mothers and grandmothers do it. But we have to tell our girls that it’s OK to be a baby girl sometimes.”

‘We had so many dreams of our son’

Gina and Peter Reeves

Gina and Peter Reeves

British-Caribbean parents Gina and Peter Reeves, also from Romford, said they were very excited to welcome their son, Danté, in 2022.

They nicknamed him “Bacchanalist” – a Trinidadian term – because he would kick inside his mother “like he was having a party”.

“We had so many dreams of our son – this Caribbean little boy, running around,” said Mrs Reeves, 42, an office manager.

However, they lost Danté at 25 weeks and have not been able to have another baby since.

“We just didn’t feel supported as a black couple together in the hospital. We just felt very let down,” said Mrs Reeves.

She said she did not feel heard by healthcare professionals throughout her pregnancy.

“I went into hospital and I was going red,” she said.

“I was clearly in pain and I couldn’t walk, and they were looking at me, like, ‘Your skin is not pale enough to notice that you are actually going red.'”

While in labour, she felt she could not scream for fear she would be treated differently.

Mrs Reeves, who has a history of miscarriage, now helps others through Ebony Bonds.

“So many black women have gone through loss and they don’t talk about it,” she said.

“We are programmed in our minds to just carry on.”

‘We know this isn’t good enough’

PA Media

PA Media

An NHS spokesperson said: “It is vital that NHS maternity services listen to all women and families and provide tailored care, particularly when need they need it most.

“While the NHS has made improvements to maternity services over the last decade, we know this isn’t good enough – much more work is needed to tackle inequalities and ensure that all women and families receive high-quality care before, during and after their pregnancy.”

Plans to support local health services have been published and the NHS said it would continue to work with government, royal colleges and others to deliver them.