‘I didn’t feel I was a good mum, or a good teacher’

Gemma Laister/BBC

Gemma Laister/BBC

Women in their 30s are, numerically, the biggest single group leaving teaching, according to new analysis seen exclusively by the BBC.

More than 9,000 of them left teaching in England 2022-23, compared with just over 3,400 men of a similar age.

In a report called Missing Mothers, researchers urge more family-friendly policies to halt the exodus.

The Labour government has promised an extra 6,500 teachers.

Keeping teachers remains a challenge. In what is a female-dominated profession, the report – released on Friday – found workload, striking a balance between teaching and family, and maternity pay, all need to be addressed.

‘Difficult decision’

The New Britain Project, an independent think tank, carried out detailed interviews with 383 women who had either stayed in teaching or left the profession.

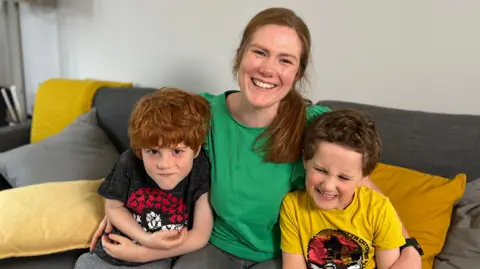

Cara Carey is one of a number of experienced teachers who quit teaching, in her case following the arrival of her second child.

“I just didn’t feel like I was a good mum, or a good teacher,” she told the BBC.

Ms Carey was teaching music and science, and was also head of sixth form, at a secondary school.

She had tears in her eyes as she described the “really difficult decision” to stop teaching.

She now works for a charity, which means that she can arrange to go to sports days, Christmas shows or school trips for her son Finley, six, and will be able to do the same with Rafi, who turns five this month.

There are currently severe teacher shortages in England in most secondary subjects. This week, the pay review body report warned only three subjects had recruited sufficient numbers of teachers into initial training.

The new analysis found women aged 30-39 have been, numerically, the largest group of teachers leaving each year since 2017.

While the number of men in their 30s leaving is lower, it’s a bigger proportion, because there are far fewer of them.

The data shows 57% of women teachers between 30-34 have dependent children under 19, and 77% of women teachers aged between 35-39 have dependent children under 19.

Nowadays, many other graduate professions offer hybrid working, with some days at home, which has led to warnings about a crisis in teacher recruitment.

One of the many hurdles is maternity pay, which under the national conditions followed by most schools in England is poor compared with other jobs.

Teachers get four weeks at full pay, followed by two weeks at 90% of pay, followed by 12 weeks of half pay topped up with the statutory maternity pay.

NHS maternity conditions provide 18 weeks at full pay, civil servants at the Department for Education are entitled to 26 weeks at full pay.

That range of 18 -26 weeks on full pay is reflected widely across the public and private sector. Tesco and Sainsbury’s both offer 26 weeks on full pay, while Lidl has increased its offer to 28 weeks.

Laura Nwanya says it “wasn’t ever an option” to have a year off when her children were born, because of the financial pressure.

When Eden, now seven, was born, she had to return to work before he was four months old – and was only able to take a few months longer with Myles because she inherited some money.

Gemma Laister/BBC

Gemma Laister/BBC

Mrs Nwanya describes the “guilt” of an early morning drop-off at 7.30am in order to be at school to teach other people’s children.

As a mum she often misses out on nativity plays and sports days and says she’s “really sad I don’t get to do the morning walk to school” despite changing schools to find a job which offers more flexibility.

The report on Friday calls for a range of measures, including giving teachers the same maternity pay as civil servants in the Department for Education.

It also highlights the need for better individual support for returning mothers, and suggests teachers are given priority for childcare places on school sites.

The most meaningful shift would be to allow more flexibility in working patterns, which economists have identified as one of the biggest challenges.

‘Gross waste of talent’

Some academy trusts are already experimenting with making teaching more appealing.

Dixons Academies Trust has said it wants to offer a nine-day fortnight for teachers in its 17 schools across the north of England.

In Cambridge, Linton Village College is part of a different group of academy schools already embracing flexible working.

Over a third of its teaching staff have arrangements such as a slightly different start or finish times, and part-time working.

It uses specific timetabling software to help manage the demand.

The principal, Helena Marsh, says this is what’s needed to stop the “gross waste of talent” that results from the loss of experienced female teachers leaving in their 30s.

Schools are facing challenges, not just from teacher shortages but also tight budgets – but the headteachers’ union ASCL said addressing the issues raised by the report was “essential”.

On maternity pay, the Confederation of School Trusts – which speaks for academy schools – said the challenge was “not the will to do it, but the finance”.

This week, the government made a small gesture towards greater flexibility – calling on all schools, rather than just some, to allow teachers to do their lesson preparation time at home.

But Anna McShane says much more is needed to keep experienced teachers, because “if we don’t focus on retention, we’re filling up a leaky bath”.

The government said it had given teachers a 5.5% award, and was making clear that teachers lesson preparation time could be carried out at home as a start.