Getty Images

Getty Images

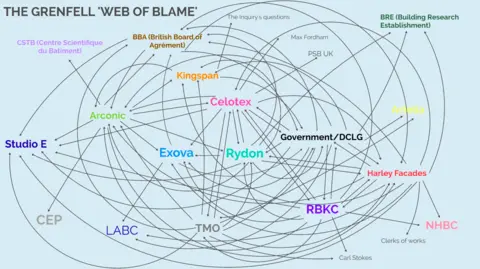

The Grenfell Inquiry’s final report sets out how a chain of failures across government and the private sector led to Grenfell Tower becoming a death trap.

The fire killed 72 people in 2017, with the cladding already found to be the “principal” reason for the blaze’s rapid spread.

On Wednesday, the final 1,700-page report of the six-year public inquiry into the fire was published.

Here are the key points from that report.

Government was warned 25 years before the disaster struck

The report by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, a retired High Court judge, says experts sounded an alarm about cladding fires in 1992 after the 11-storey Knowsley Heights tower caught alight in Huyton, Merseyside.

Seven years later there was another fire at Garnock Court in Irvine, North Ayrshire, and a committee of MPs repeated the concerns.

But the flammable cladding wasn’t banned because it had already been classed as meeting a British safety standard.

Fire tests proved how dangerous the cladding was

Safety tests in 2001 revealed the type of cladding of concern “burned violently”. The results were kept confidential and the government did not tighten any rules.

“We do not understand the failure to act in relation to a matter of such importance,” the inquiry panel said.

Eight years later in 2009, six people died in a fire at Lakanal House, a high rise in South London. The coroner at their inquests asked for a review of building regulations but, the inquiry found, this was “not treated with any sense of urgency.”

Grenfell Inquiry

Grenfell Inquiry

The 2010 coalition government ignored risks

In 2010 the coalition government headed by David Cameron was on a mission to cut regulations – which it had dubbed as “red tape” holding back British enterprise.

The inquiry found this policy so “dominated” thinking in government that “even matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded.”

The inquiry found that the then housing department was “poorly run” and fire safety had been left in the hands of a relatively junior official.

Privatisation of a key body added to problems

The Building Research Establishment (BRE) is a key body in the UK that was set up 100 years ago to help deliver quality science-led standards for the construction industry. It is the government’s expert adviser.

The BRE was privatised in 1997 – but the inquiry said it then became exposed to “unscrupulous product manufacturers.”

Dangers were ‘deliberately concealed’

The inquiry found there had been “systematic dishonesty” from those who made and sold the cladding.

Arconic, a manufacturer, “deliberately concealed” the true extent of the danger of the cladding used to wrap Grenfell Tower. Fire tests it commissioned showed the cladding performed poorly but this information was not given to the BBA, a British private certification company tasked with keeping the construction industry up to date.

This “caused BBA to make statements that Arconic knew were ‘false and misleading’”, the report said.

Two firms made the insulation inside the cladding panels – Celotex and Kingspan.

Celotex made “false and misleading claims” about its product being suitable for Grenfell, said the inquiry. Kingspan, the inquiry said, misled the market by not revealing the limitations of its product.

Council body showed ‘indifference’

The inquiry said Grenfell’s refit was poorly managed by contractors and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea’s company that ran social housing, known as a Tenant Management Organisation (TMO).

The inquiry said there had been a breakdown in trust and relations between the TMO and residents, which led to a “serious failure to observe responsibilities”.

It showed a “persistent indifference” to fire safety and the needs of vulnerable residents.

When the TMO had to replace self-shutting fire doors in the block – a key safety measure to prevent spread of smoke and flames – it did not order the correct specification that would improve the chances of residents being rescued.

‘Scant attention’ paid to obligations

The inquiry said that during the refit of the building there was a failure to establish who was responsible for safety standards.

Studio E, the architect, Rydon, the principal contractor, and Harley Facades, the cladding sub-contractor, “all took a casual approach to contractual relations,” said the report.

“They did not properly understand the nature and scope of the obligations they had undertaken, or, if they did, paid scant attention to them.”

The inquiry said Studio E “bears a very significant degree of responsibility for the disaster” before it had failed to recognise the cladding was combustible.

Harley Facades “bears significant responsibility” because it had not concerned itself with fire safety at any stage.”

Rydon failed to make clear which contractor was responsible for what – and it failed “to take an active interest in fire safety.”

London Fire Brigade bosses didn’t prepare their teams

The LFB had known since the 2009 Lakanal fire that it faced challenges in fighting blazes in high-rise blocks. The firefighters who went into Grenfell had not been prepared for what they had to battle through to try to save lives.

The inquiry said senior officers had been complacent and lacked the skills to recognise the problems and correct them. There was a failure to share knowledge about cladding fires, a failure to plan for a large number of 999 calls, or train staff in what to tell trapped residents.

And so the disaster was the product of ‘decades of failure’

The inquiry pulls no punches in concluding that the path to disaster began many years ago.

It says that the way building safety is managed in England and Wales is “seriously defective”. It recommends a single regulator, answerable to a government minister, so that officials and the industry can be held to account.