Police knew murder suspect intended to kill a black man

By Sanchia Berg, BBC News

BBC

BBC

The police file on one of the UK’s most notorious unsolved murders shows a prime suspect had told officers he intended to kill a black man.

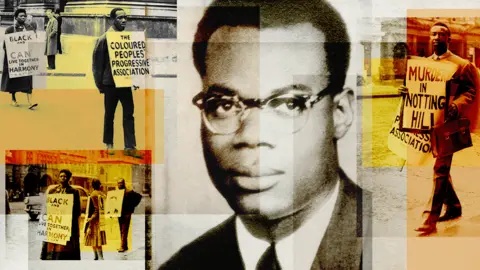

Kelso Cochrane, a carpenter from Antigua, was stabbed to death in May 1959, during an attack by a white gang in Notting Hill, west London. No-one was ever charged.

The murder came a year after the 1958 Notting Hill race riots, but police said there was no racist motive and that Cochrane had been killed for money.

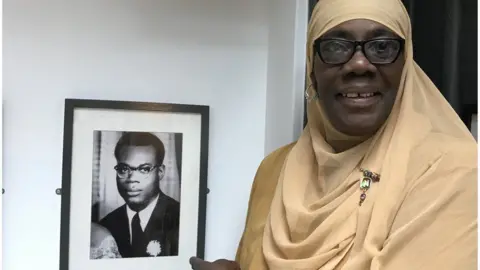

For years, requests to release the file were rejected but members of Cochrane’s family obtained it through a Freedom of Information request.

Millicent Christian, daughter of Cochrane’s cousin, says it was “so emotional” to hear the file was being opened. But now, after reading the first tranche of papers, both she and her brother Louie have “mixed feelings”.

The file reveals that one of the suspects, John William Breagan, had already been jailed for stabbing three black men, and had told police at the time of his arrest for that crime that he would kill the first black man he saw after his release.

Cochrane’s murder came 10 days after Breagan left prison.

With that evidence available at the start, Millicent and Louie cannot understand why the investigation never progressed.

“Within two months of the murder officers are admitting it was unlikely to be solved,” says Louie. “That’s crazy.”

The murder

The file contains a wealth of detail about the events surrounding the killing and the police investigation.

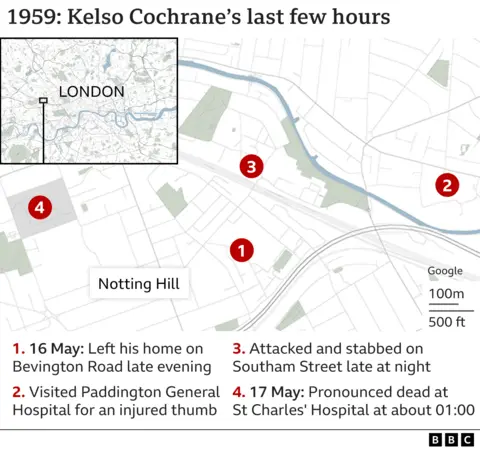

The attack occurred on the night of 16 May 1959, as 32-year-old Cochrane was returning from Paddington General Hospital, where he had received treatment for a broken thumb.

His fiancee, Olivia Ellington, told police he had already had medical treatment once but his thumb was still hurting and he couldn’t sleep. So he got up and went back to hospital.

It was on his return that a gang of white men surrounded him on Southam Street in Notting Hill, near the junction with Golborne Road. Two Jamaican passers-by came to his rescue and took him to another nearby hospital, where doctors discovered he had been stabbed in the chest with a very thin blade. Cochrane was pronounced dead at 01:00 in the morning on 17 May.

Even though white youths had attacked black residents in Notting Hill a year before, this was the first time a black person had been killed in the area. It made the papers’ front pages and caused widespread alarm, especially among the Windrush generation.

The investigation

Det Supt Ian Forbes-Leith took on the case hours after the murder, and deployed a large team to start house-to-house enquiries.

Dr Mark Roodhouse, an expert on policing in London in the 1950s, describes the first stage of the investigation as very thorough.

“It quickly led to them identifying key suspects,” he says.

“But when the next stage developed, which was interrogating those suspects, things seem to slow down.”

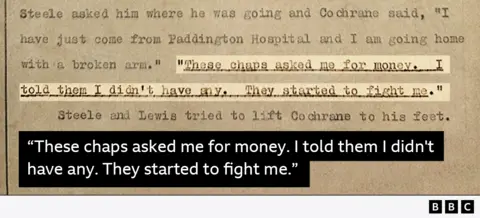

Officers began by interviewing witnesses. One of the Jamaicans who had helped Cochrane remembered him saying: “Those chaps asked me for money. I told them I didn’t have any. They started to fight me.”

Some other people who had seen the attack were reluctant to talk, a police report in the file says.

Two women who had watched what happened from their windows were described as “evasive”. “One feels they are not telling all they know,” the report says.

Another witness, Michael Behan, said he saw two white youths running to the junction where the attack took place. He identified one as John William Breagan, who was 24.

Breagan had been at a party nearby, along with Patrick Digby, who was 20, and a group of their friends – all young white men, many with criminal records.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Digby was interviewed just after 18:00 on Monday 18 May. He initially denied leaving the party. He said he had got drunk and “passed out” – only waking in an armchair at about 08:00 the following morning.

He was interviewed again two hours later, and this time admitted leaving the party with John Breagan, known as “Shoggy”. He said they had got into an argument with someone and went for a walk to “cool their feelings”.

A group of white youths passed them, he told police, walking in the direction of Southam Street. When he and Breagan turned into the street, there was no sign of the youths but they saw a black man sitting in the gutter. They then saw two other black men come to the seated man’s aid.

This statement was of “paramount importance” to police: it put Digby at the scene. They detained him, and searched for Breagan.

Prime suspects

By 01:00 in the morning of 19 May Breagan was being interviewed too. He told police that he and Digby had left the party to look for girls, as there “wasn’t enough to go round”.

He claimed they went for a walk and saw a black man sitting down in Southam Street. Breagan said he told Digby: “Come on. We don’t want to get any trouble with people like that.”

Police described this account as “most unsatisfactory”. They believed Breagan and Digby “had put their heads together and concocted a story to account for their presence at the scene of the attack if they happened to be identified by witnesses”.

But their stories were contradictory. The police recognised that “obviously one or both were lying” about why they had left the party. They detained Breagan too.

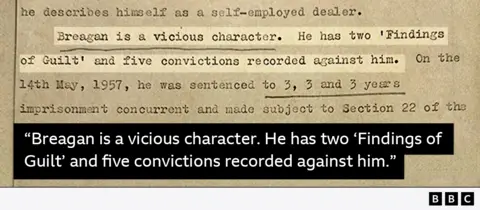

While Digby was “a known troublemaker” according to the police, Breagan was a far more “vicious” character. Two years earlier he had been sentenced to three years in prison for three separate unprovoked attacks on black men, all on the same day, stabbing them in the face and the body.

It was when he was arrested for these offences that he told two police officers, using a racial slur: “If I do time for this, when I come out I’ll kill the first [black person] I see. I mean that too.”

Cochrane was murdered 10 days after Breagan was released.

Millicent Christian says she was “speechless” when she saw this comment in the files.

“How could police miss this?” she says. “He has said exactly what he was going to do.”

In one of the newly released documents, police described Breagan and Digby as “strong suspects”. Over the next 48 hours all efforts were concentrated on them.

But although they had good evidence that racism could be a factor, publicly the police ruled it out.

A senior Scotland Yard told journalists that officers were satisfied “it was not a racial killing” and that robbery had been the motive.

Mark Olden, the author of an investigation into the case, Murder in Notting Hill, says that after the riots in 1958, there was concern at the highest levels about reaction to the Cochrane murder.

He says the only explanation is that police were “concerned about a repeat or worse of the race riots of the year before” and that “public order concerns were foremost in their minds”.

At the time, he adds, everyone in the local community “thought it was a racist attack”.

At about 19:00 on 20 May, Breagan said he wanted to do another interview. This time he said he had stopped Digby from getting into a fight at the party, and had suggested they go for a walk.

The file doesn’t indicate why he changed his statement, which now tallied with Digby’s. Mark Olden – who spoke to Breagan before he died – says he told him they had been held in adjacent cells at the police station, which allowed them to communicate and “straighten” their stories.

Police wrote that they were now “reluctantly obliged” to release both men without charge.

‘Squalid slum area’

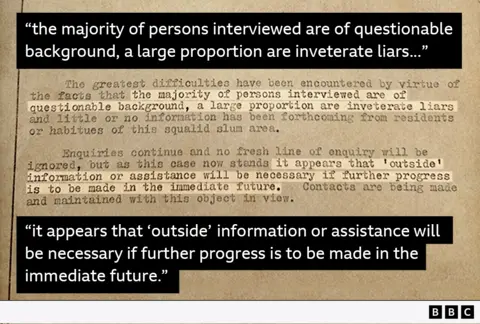

Nearly 1,000 people had been interviewed by mid-July, when Det Supt Forbes-Leith produced a report to sum up what had been achieved.

“Despite the most exhaustive enquiries… not one shred of evidence has been forthcoming to suggest who the culprits were,” he wrote.

He noted there was a “general feeling” that Digby and Breagan were responsible, together with others who had been at the party with them. But he added: “This, however, is surmise and not one of the group has had a finger pointed at him with certainty.”

His views were echoed by his superior officer, Chief Supt James Dunham, who said that despite prolonged interrogation of the two suspects and “scientific examination” of their clothing nothing had emerged to connect them to the “murderous act”.

Dunham said a large proportion of those interviewed were “inveterate liars”.

“Little or no information has been forthcoming from residents or habitues of this squalid slum area,” he wrote. The only way to make progress would be to use “‘outside’ information or assistance”, he said.

It is not clear what this means.

Certainly, the case did not move forward from that point.

Both prime suspects – Breagan and Digby – are now dead, along with many of the witnesses.

Yet for decades the Metropolitan Police said the case was still open. So even though the files had been transferred to the National Archives, they could not be released because information might prejudice the “detection of crime”, under Section 31 of the Freedom of Information Act.

Over the years many people have tried to get the files open – including me. But the Kelso Cochrane family, with expert legal support, assembled a comprehensive Freedom of Information application. When it was turned down, they appealed and won.

The Metropolitan Police told us that “our thoughts remain with Mr Cochrane’s family”, and that any new evidence that came to light would be “assessed and investigated accordingly”.

Before he came to the UK Kelso Cochrane had lived in the US. He had married there and had a child. His daughter Josephine never knew him growing up, because he was killed when she was still very young.

She told us: “There is some joy that I found him. There’s some joy that I could talk about him to my grandchildren and children.”

She says she wasn’t surprised that the prime suspects were detained so quickly, that one had even threatened to kill a black man, and yet the investigation didn’t progress.

“It’s normal to me,” she says. “This is what happens in the world. This is how certain people are treated and certain people act. People know they can get away with things.

“When a black person is murdered it starts out that the police are investigating and by the end of the month they’re not investigating any more. And if people like me don’t chase, to find out what happened to our family members… it’ll just go in the archives. That’s just how people like me have been treated in the United States and all over the world.”

The police file is being released in sections, as some redactions are being made for data protection reasons. There are several more tranches to come.