Cheshire Police

Cheshire Police

Lucy Letby has become arguably the most notorious serial killer of modern times.

Convicted of killing seven babies in her care and attempting to kill seven others – the former neonatal nurse will die in prison.

But for some time now, a growing number of experts have been raising concerns about her trials, claiming that vital evidence may have been misinterpreted.

Others insist that much of the debate is misguided and there is no evidence to show that the trial was in any way unfair or unreliable.

An inquiry into the Countess of Chester Hospital and the NHS’s handling of the whole matter is set to begin on 10 September.

Letby’s murder trial last year was one of the longest in British legal history, following a six-year police investigation – and was followed by a retrial after a verdict on allegations concerning one baby could not be reached.

Cheshire Police

Cheshire Police

Six expert medical witnesses and many former colleagues testified against her. Thousands of documents were presented by the prosecution and pored over in many months of painstaking examination.

Their case was wide ranging, including blood test results which showed that two babies had been given an insulin overdose, X-rays which indicated that air had been injected into seven others, while others still were shown to have been force-fed with milk.

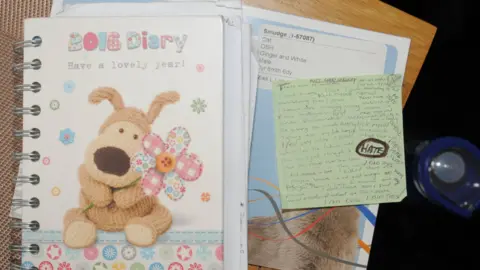

Then there were the notes at Letby’s house which appeared to contain confessions – one reading “I am evil” – and the frequent social media searches she made for the families of the babies who had died, which lawyers maintained was the nurse showing a morbid curiosity to witness the effect she had on their lives.

A staffing rota also showed she had been on duty for every suspicious death or collapse between June 2015 and June 2016.

The rota was a key part of the case – a striking visual symbol of the case against her. But a number of statisticians have publicly questioned its usefulness.

One is Peter Green, a professor of statistics and a former President of the Royal Statistical Society.

“The chart appears to be very convincing, but there are a number of issues with it,” he said.

“A big thing is that it only describes 25 of the bad events which happened in this period.

“It doesn’t include any of the events that happened when Lucy was not on duty.”

Helen Tipper

Helen Tipper

During this period, there were at least six other deaths and numerous collapses.

Prof Green said the chart also does not reflect the fact that Letby was working extra shifts.

“It’s a natural human thing. We all see patterns that are not there,” he said.

“The danger is that this evidence can be very compelling to the non-professional, and over interpreted.”

Another crucial part of the prosecution’s case were blood samples from babies who had collapsed with low blood sugar.

They showed exceptionally high levels of insulin and low levels of a substance called C-peptide.

That combination is only generally seen when the body takes in synthetic insulin, leading to the charge that Letby had deliberately poisoned the babies by adding it to their nursery feed bags.

Prof Alan Wayne Jones, an expert in forensic toxicology, is one of those who has challenged the results.

He pointed out that the test used measures the body’s reaction to insulin rather than the substance itself.

“The problem is that the method of analysis used [in these two cases] was probably perfectly good from a clinical point of view, but not a forensic toxicology point of view,” he said.

“That test cannot differentiate between synthetic insulin and insulin produced by the pancreas.”

Cheshire Police

Cheshire Police

The testing lab’s own website states that if synthetic insulin is suspected, the results should be verified externally by a specialist centre.

Clinicians at the Countess of Chester did not do that because thankfully both babies recovered.

At the time, there was no suspicion of deliberate harm.

Prof Jones said he has no doubt they suffered sharp drops in blood sugar levels, but that there could be another natural explanation for why that had happened.

Others have also questioned the charge that Letby injected air into babies’ blood vessels with often fatal consequences.

They were each found to have air bubbles in their blood, known as an embolism.

A number of clinicians also described witnessing unusual and sudden rashes in these infants.

The prosecution quoted a paper on the phenomenon, written in 1989 by Canadian neonatologist Dr Shoo Lee, which described a distinctive rash of bright pink blood vessels against a blue skin as an indicator of air embolism.

But in April at Letby’s Court of Appeal hearing, Dr Lee spoke for the defence.

He said the distinctive rash he had outlined was not that described by witnesses in her case.

Dr Lee was not called at the original trial. The defence did not call any expert witnesses – just Letby herself and the hospital plumber, who testified that there had been drainage problems in the unit.

By contrast, six expert witnesses testified for the prosecution.

Much of the case relied on the testimony of Dr Dewi Evans, a former paediatric consultant with decades of experience as an expert witness.

PA Media

PA Media

He said he had read 18 research papers in total on air embolism, highlighting different indications.

In other words, he was not just relying on Dr Lee’s report.

He also pointed out that his findings were backed up in court by a radiologist and a neonatal pathologist.

He added that the cases on the rota were there because, after reviewing all the deaths and collapses, he thought only they were suspicious or unexpected.

He said he had not known at that point that Letby had been on duty and this had only been revealed afterwards by Cheshire Police.

Dr Evans also made the point that none of those raising concerns had seen the patient notes.

The Court of Appeal spent three days listening to the defence and prosecution arguments but ultimately rejected the case, and a 58-page judgement explains their conclusion.

In the case of Dr Lee’s testimony, the court found that Dr Evans had relied on numerous sources to come to his conclusions, including those other research papers, X-rays and the opinions of other experts.

None of this has convinced those fighting to have it heard again, who point to previous occasions when the Appeal Court has got it wrong.

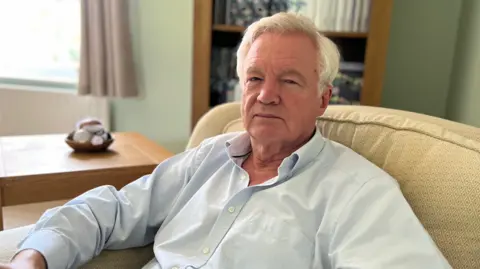

Veteran MP Sir David Davis has a history of championing successful miscarriage of justice cases.

Most recently, he helped Mike Lynch, the tech entrepreneur who successfully fought a 12-year legal battle in the USA, but died after a freak storm engulfed his yacht earlier this month.

Sir David said he had started off by thinking that Letby was guilty.

His doubts began in May after he raised a question in the House of Commons on why a critical piece in an American magazine was not allowed to be published here.

This was before the second trial and British contempt laws do not allow publication of anything which could influence the jury.

“It was only the fact that I got authoritative calls from people who really know about statistics, about medicine, about science, about law, and I’d never had anything like this happen before,” he said

“I started to think – it’s a terrible crime, but if they’ve got it wrong, it’s a terrible miscarriage of justice.”

Sir David said he believed other possibilities for the deaths could have included a lack of staffing and training on the unit and an infectious outbreak, possibly linked to the faulty drainage discussed in the trial.

“All of us find it easier to believe that a villain has killed people rather than a system or a random act,” he said.

He is now reading through thousands of documents detailing the trial before making a decision on whether to take the case up and press for the Criminal Cases Review Commission to get involved.

Sir David said he already believes that the trial was flawed but by itself that does not mean Letby is not guilty.

He added that he will not take it further unless he comes to the conclusion that she was probably innocent.

Some of the parents of the babies who died have spoken of their pain at seeing doubts being raised on the convictions.

Sir David said he does think about this and understands that they have gone through years of suffering.

But he said if the conviction is proved to be unsafe, it is important to look at other reasons which may have led to what happened.

“If we have got this wrong it’s not just that we’ve put a young woman in prison for the rest of her life effectively, it is also that we haven’t answered by these babies died, and why other babies may die,” he said.

But others question the basis for claims that the trial was flawed.

Barrister Tim Owen KC has spent 40 years as a defence lawyer, and worked on many cases which he successfully referred back to the Court of Appeal and the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

He also co-hosts a legal podcast, Double Jeopardy, which has examined the Letby debate.

Much has been made of the fact that the Letby case relied on circumstantial evidence and no-one definitively saw her harming any of the babies.

Mr Owen said this point is far less relevant than many might think.

“Some people believe that circumstantial evidence isn’t really evidence,” he said.

“That’s simply not true.

“A circumstantial case can be a powerful case but in order to understand it, you have to look at the totality.

“You can’t just pick one little bit and say, ‘Oh look at that, that’s unreliable,’ or ‘That doesn’t prove anything’.”

Mr Owen said no-one knows exactly why the two expert witnesses instructed by Letby’s defence team were never called.

He said one conclusion would have to be that the defence decided the testimony would not help their case.

He stressed he had no personal view on Letby’s guilt or innocence and underlined that he had dealt with many miscarriages of justice, but added that as it stands, there is no proof that this is one.

“There needs to be something new and compelling which calls into question the fundamental case theory presented to the jury at two trials,” he said, adding that so far, he has not seen that.

“I’m seeing lots of people putting forward theories. They are making assumptions without the solid basis for it.”

But still the questions continue. This week a private letter signed by 24 experts asked for the forthcoming Letby inquiry to either be delayed or to change its terms of reference to reflect the current debate.

One of the signatories, statistician Prof Peter Green, said he too has no view on Letby’s guilt.

“I have no idea whether she is innocent or not,” he said.

“My concern is simply about the possibility that this was not a safe conviction.”

Forensic toxicologist Alan Wayne Jones agreed.

“I don’t know whether she’s guilty or not,” he said.

“I don’t think anyone knows except Lucy Letby.”