The Pennsylvania voters who ‘could make or break the election’

BBC

BBC

Bill Donovan knows that every vote matters in the swing state of Pennsylvania.

That’s why the 78-year-old Democrat travelled from university to university throughout Pittsburgh to approach students in coffee shops and on sidewalks to ensure they registered to vote.

Mr Donovan plans to back Vice-President Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election and volunteers with a non-profit voter registration group aimed at boosting Democratic turnout in the state.

With 19 electoral votes – the most electoral votes out of any swing state – Pennsylvania has become this election’s must-win prize, shining a spotlight on everyday voters.

- Harris v Trump poll tracker

- What is the electoral college?

- A guide to Pennsylvania

- ‘It’s non-stop’: Swing state voters bombarded with ads – will they make a difference?

Mr Donovan said they have to take advantage of it.

“A lot of people are saying this is where it’s going to be decided… and I think they might be right,” he told the BBC. “That gives us just a little more incentive to keep going when we feel like going home.”

How Pennsylvania votes is often seen as a predictor of who will win the country – the candidate who has won the state in 10 of the last 12 presidential elections landed in the White House.

The state has a history of close races. Former President Donald Trump carried Pennsylvania in 2016. Four years later, President Joe Biden narrowly won. And with just days to go before election day, polls show it’s a dead heat between Harris and Trump.

The power that comes with casting a vote in Pennsylvania is exactly the reason Dimitri Chernozhukov, a 21-year-old university student at Lafayette College in the city of Easton, chose to attend university in the state.

“My vote matters here,” said the soon-to-be, two-time Trump voter. “When I was registering in Pennsylvania, I made sure all the forms were correct because this vote matters.”

The state has been inundated with campaign stops from both Harris and Trump, who along with their running mates, have made more than 50 appearances total in the state since mid-July.

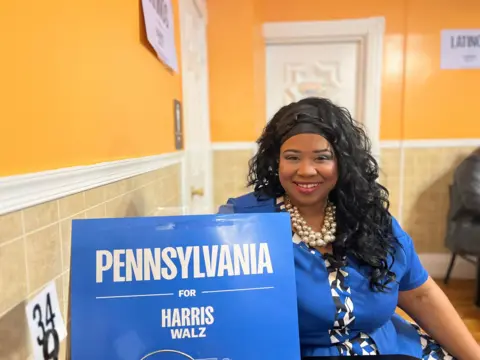

Kari Holmes, a pastor in eastern Pennsylvania, sees the limelight on her state and feels the weight of being one of its highly coveted voters. She has been working with other faith leaders to encourage voters of colour – a highly sought after demographic – to cast a ballot.

“This is the time to feel the gravity of our vote as voters of colour in this very important commonwealth,” Ms Holmes, who plans to vote for Harris, said.

With some nine million registered voters in Pennsylvania, turnout is essential for success for either campaign come November.

Registration numbers show that political affiliation is split nearly 50-50, with around 3.9 million registered Democrats and 3.6 million registered Republicans. There are also around 1.4 million Independent or third-party registered voters, who both campaigns have courted.

Marc Pane, owner of an auto-repair business in the city of Scranton, is among those millions of registered Republicans excited to cast his ballot for Trump this November.

“It could come down to Pennsylvania,” Mr Pane said. “We could make or break the election. It’s important. Our vote is important, more so than ever and I’m really kind of happy it’s us.”

In Pennsylvania, Democrats are mostly clustered along the eastern and western borders in urban areas like Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. The middle of the state, which is rural, leans heavily Republican.

Two counties specifically – Erie in western Pennsylvania and Northampton in eastern Pennsylvania – are seen as bellwether counties, meaning they often trend with how the overall country votes. Both counties favoured Trump in 2016, but went for Biden in 2020.

“They have the balance of urban, rural, suburban and it’s really a place to look on election night to see what’s happening,” Christopher Borick, director of Pennsylvania’s Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion, told the BBC.

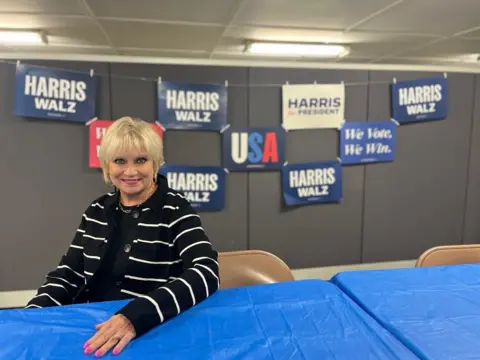

Lori McFarland, chair of the Lehigh County Democrats, spends her days working to ensure Pennsylvanians in Lehigh County, which neighbours Northampton County, back Harris. She is not so sure every voter understands the gravity of their decision come 5 November.

“It’s challenging to not get overexcited, stay calm, stay focused and know what the job is,” Ms McFarland said. “There is pressure because both the campaigns [and] the world is looking at not only Lehigh and Northampton counties, they are also looking at Erie County.”

“We are the three major counties that feel like it’s falling on us, it’s overwhelming,” she told the BBC.

The focus on courting voters in the crucial swing state leads to an influx of political advertising.

Between 22 July and October 8, the Harris campaign spent $159.1m (£122.6m) on advertising in Pennsylvania, according to a recent AdImpact report. The Trump campaign spent $120.2m (£92.4m) in the same time period.

Andy Jones, who is voting for Trump in Allegheny County, said television and radio advertisements, billboards and yard signs in western Pennsylvania are “out of control”. He describes it as a battle among his neighbours to see who can “out-sign” the other in their yards.

“People are definitely charged up around here,” he said. “It’s an important state.”