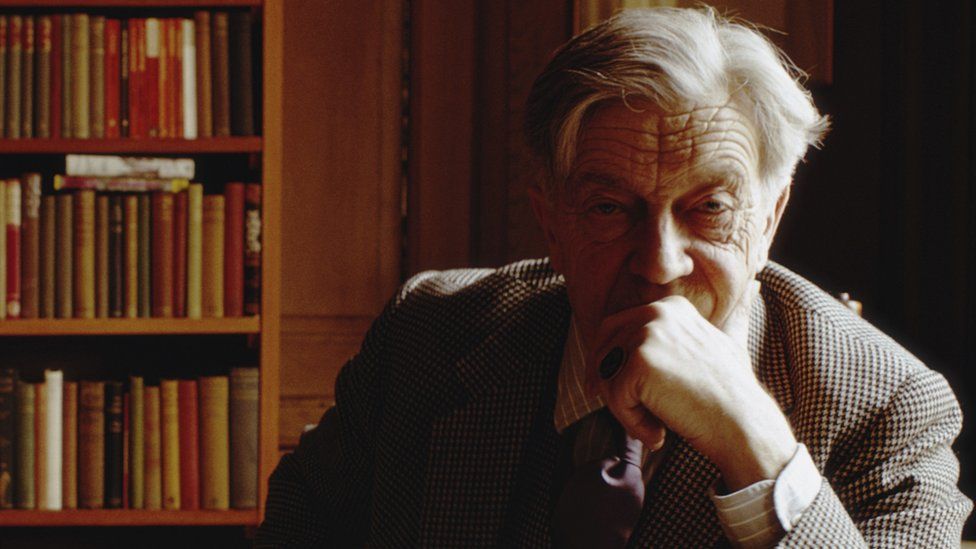

Cecil Day-Lewis was appointed poet laureate in 1968

Some of the greatest English poets of the 20th Century were ruled out by Downing Street as candidates for poet laureate, government files reveal.

Names such as WH Auden, Philip Larkin and Robert Graves were passed over as being unsuitable.

The job dates back to the 17th Century, and has been filled by some of the most celebrated poets in history, including Tennyson and Wordsworth.

The papers, released on Wednesday, date from the 1960s to the 1980s.

In May 1967, the appointments secretary at 10 Downing Street found himself having to draw up a list of the country’s best poets. The incumbent, John Masefield, had died after 37 years in the post.

It was the middle of the so-called “swinging ’60s” and the idea of a poet laureate seemed archaic to many.

But poetry was increasingly popular, thanks to the work of a new generation of writers, like Allen Ginsberg in the US, and the Liverpool poets in Britain.

Harold Wilson, the prime minister, was in no rush to make a decision. John Hewitt, who was appointments secretary at Number 10, was told to investigate potential candidates.

Image source, Corbis via Getty Images

Yorkshire-born WH Auden was considered ineligible as he had become a US citizen in 1946

He approached leading figures in the arts, as well as dons at Oxford and Cambridge. Dame Helen Gardner, Merton Professor of English at Oxford, had some “fairly caustic” comments about the “present quality of poetry” and the “lack of any outstanding talent”, the papers reveal.

Auden was excluded because he was an American citizen. John Betjeman was one of the most popular poets. But Dame Helen described him as “a lightweight, amusing but rather trivial”. He had “critical views about the establishment”, she said, which deemed to be not appropriate.

Robert Graves was “probably the best poet available”, she added, but his “manner of life must surely rule him out”. Graves had criticised the role and spent most of his time in Majorca.

Image source, Getty Images

Stevie Smith was not a popular choice with the poetry establishment

The popular poet Stevie Smith she dismissed as “absurd”. She “wrote ‘little girl poetry’ about herself mostly.” Cecil Day-Lewis was “a possible” – he produced “run of the mill poetry but nothing particularly outstanding”.

That view was echoed by the chair of the Poetry Society, Geoffrey Handley-Taylor. He told Hewitt that Graves was “too peculiar” and “too anti-establishment”. Betjeman, he said, “called himself a poetic hack and there was some truth to this”.

He described Smith as “unstable”. By contrast Day-Lewis was “a good administrative poet” and “a safe bet”.

As the months passed, more names were put forward. Some nominated themselves. Allen Ginsberg proposed the singer Donovan, just 21, whose work “Sunshine Superman” and “Mellow Yellow” had topped the charts. In August, Ginsberg sent a hand drawn “flower card” to Number 10 with the words “Donovan for Laureate”. Officials did not respond.

Image source, National Archives

US beat poet Allen Ginsberg was an advocate of Scottish singer-songwriter Donovan for the post

On September 14, 1967, Hewitt wrote to the prime minister proposing Day-Lewis. The alternative, Betjeman, would be a “backward-looking choice”, he said. He had been described as “the songster of tennis lawns and cathedral cloisters”.

Harold Wilson agreed, but he wanted Hewitt to explore the possibility of appointing additional poets laureate for Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. That was not pursued, and in January 1968, the announcement was made.

But four years later, the search began again, after Day-Lewis died.

Auden was again under consideration, according to newspaper reports, and apparently the bookies’ favourite.

Number 10 was warned by Ross McWhirter – of the Guinness Book of Records – that Auden was said to be the author of a “pornographic” poem entitled “The Gobble”, published in an underground magazine.

McWhirter worried that if Auden were selected this could “bring disgrace upon the appointment” and this would reflect on the Queen herself. The now-Sir John Hewitt told him Auden wasn’t on the shortlist.

This time Philip Larkin was under serious consideration – described by Hewitt as “a first-rate craftsman”. But the critic Jon Stallworthy warned Larkin disliked public speaking. Officials were advised he was a “reserved” man who would not be an ambassador for poetry.

Image source, Getty Images

Philip Larkin was passed over because officials were advised he was a “reserved” man

The so-called “poets’ conference”, representing younger writers, suggested Adrian Mitchell and George MacBeth – but they didn’t make it into the final selection.

Then Prime Minister Ted Heath, picked Betjeman- who accepted, writing that he was “honoured and delighted and at the same time humbled”.

A trying year

In 1984, a new laureate was needed, following Betjeman’s death. There is no discussion of merit in the file.

Mrs Thatcher’s officials put together a list of names and recommendations. Larkin was the most popular choice, but one unnamed figure objected.

Ted Hughes was picked, even though only two people proposed him – and no explanation was given.

The trial of selecting a new laureate following the death of the previous one is now a thing of the past. Whereas it used to be a lifetime post, since 1999, the appointment has been for a fixed term of 10 years. Current incumbent Simon Armitage’s tenure runs until 2029.

Reacting to the newly declassified files, Mark Ford, Professor of English at University College London, said: “The laureateship is such a peculiar role that finding a suitable candidate is not easy – 1967 was clearly a particularly trying year.”