How a communist from the Tata family became one of Britain’s first Asian MPs

Picryl

Picryl

The name Shapurji Saklatvala may not be one that leaps out of the history books to most people. But as with any good tale from the past, the son of cotton merchant – who is a member of India’s supremely wealthy Tata clan – has quite a story.

At every turn, it seems that his life was one of constant struggle, defiance and persistence. He shared neither the surname of his affluent cousins, nor their destiny.

Unlike them, he would not go on to run the Tata Group, which is currently one of the world’s biggest business empires and owns iconic British brands like Jaguar Land Rover and Tetley Tea.

He instead became an outspoken and influential politician who lobbied for India’s freedom in the heart of its coloniser’s empire – the British Parliament – and even clashed with Mahatma Gandhi.

But how did Saklatvala, born into a family of businessmen, pursue a path so different from his kin? And how did he blaze a trail to become one Britain’s first Asian MPs? The answer is as complex as Saklatvala’s relationship with the his own family.

Getty Images

Getty Images

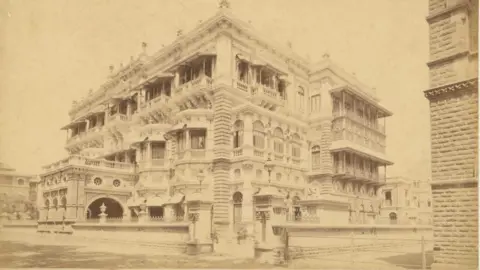

Saklatvala was the son of Dorabji, a cotton merchant, and Jerbai, the youngest daughter of Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, who founded the Tata Group. When Saklatvala was 14 years old, his family moved into Esplanade House in Bombay to live with Jerbai’s brother (whose name was also Jamsetji) and his family.

Saklatvala’s parents separated when he was young and so, the younger Jamsetji became the main paternal figure in his life.

“Jamsetji always had been especially fond of Shapurji and saw in him from a very early age the possibilities of great potential; he gave him a lot of attention and had great faith in his abilities, both as a boy and as a man,” Saklatvala’s daughter, Sehri, writes in The Fifth Commandment, a biography of her father.

But Jamsetji’s fondness of Saklatvala made his elder son, Dorab, resent his younger cousin.

“As boys and as men, they were always antagonistic towards each other; the breach was never healed,” Sehri writes.

It would eventually lead to Dorab curtailing Saklatvala’s role in the family businesses, motivating him to pursue a different path.

But apart from family dynamics, Saklatvala was also deeply influenced by the devastation caused by the bubonic plague in Bombay in the late 1890s. He saw how the epidemic disproportionately impacted the poor and working classes, while those in the upper echelons of society, including his family, remained relatively unscathed.

During this time, Saklatvala, who was a college student, worked closely with Waldemar Haffkine, a Russian scientist who had to flee his country because of his revolutionist, anti-tsarist politics. Haffkine developed a vaccine to combat the plague and Saklatvala went door-to-door, convincing people to inoculate themselves.

“Their outlooks had much in common; and no doubt this close association between the idealist older scientist and the young, compassionate student, must have helped to form and to crystallise the convictions of Shapurji,” Sehri writes in the book.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Another important influence was his relationship with Sally Marsh, a waitress he would marry in 1907. Marsh was the fourth of 12 children, who lost their father before becoming adults. Life was tough in the Marsh household as everybody had to work hard to make ends meet.

But the well-heeled Saklatvala was drawn towards Marsh and during their courtship, he was exposed to the hardships of Britain’s working class through her life. Sehri writes that her father was also influenced by the selfless lives of the Jesuit priests and nuns under whom he studied during his school and college years.

So, after Saklatvala travelled to the UK in 1905, he immersed himself in politics with an aim to help the poor and the marginalised. He joined the Labour Party in 1909 and 12 years later, the Communist Party. He cared deeply about the rights of the working class, in India and in Britain, and believed that only socialism – and not any imperialist regime – could eradicate poverty and give people a say in governance.

Saklatvala’s speeches were well received and he soon became a popular face. In 1922, he was elected to parliament and would serve as an MP for close to seven years. During this time, he advocated ferociously for India’s freedom. So staunch were his views that a British-Indian MP from the Conservative Party regarded him as a dangerous “radical communist”.

During his time as an MP, he also made trips to India, where he held speeches to urge the working class and young nationalists to assert themselves and pledge their support for the freedom movement. He also helped organise and build the Communist Party of India in the areas he visited.

Getty Images

Getty Images

His strident views on communism often clashed with Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent approach to defeat their common adversary.

“Dear Comrade Gandhi, we are both erratic enough to permit each other to be rude in order to freely express oneself correctly,” he wrote in one of his letters to Gandhi, and proceeded to mince no words about his discomfort with Gandhi’s non-co-operation movement and him allowing people to call him “Mahatma” (a revered person or sage).

Though the two never reached an agreement, they remained cordial with each other and united in their common goal to overthrow British rule.

Saklatvala’s fiery speeches in India perturbed British officials and he was banned from traveling to his homeland in 1927. In 1929, he lost his seat in parliament, but he continued to fight for India’s independence.

Saklatvala remained an important figure in British politics and the Indian nationalist movement until his death in 1936. He was cremated and his ashes were buried next to those of his parents and Jamsetji Tata in a cemetery in London – uniting him once again with the Tata clan and their legacy.

Read more BBC stories on forgotten Indians: