Reuters

Reuters

Ever since the Southport attack in July, social media has been awash with misinformation, rumours and lies about what happened and how the criminal justice system is handling the case.

The rules and complexities of how our prosecutions work mean there are limits on what the public can know before there has been a verdict in court.

Why don’t we know all the facts about what happened in Southport?

This has been the most common question all over social media from day one.

There is a universal rule covering all criminal cases in England and Wales which means that before a trial takes place, there can be no reporting of anything that might prejudice or impede the course of justice in the case.

This is not a ban on the truth.

It is a postponement of reporting the details to ensure that a jury is not influenced and base their decision solely on the evidence they hear in court. It is how our justice system tries to guarantee all defendants receive a fair hearing.

Other countries, notably the United States, think this is unnecessary. And many British journalists (I declare an interest) think these rules – part of what is known as Contempt of Court – need rethinking.

That said, some facts can always be reported before trial.

When I or colleagues stand outside court, you’ll see us explaining the allegations and who a defendant is.

None of that influences a jury because it does not get into the detail of what a defendant may have actually done or not done.

That’s why in the Southport case, and faced with an astonishing online rumour mill suggesting the suspect was an illegal immigrant, Merseyside Police clarified that the 17-year-old they’d arrested had been born in Cardiff.

Later, a judge allowed the media to name him, lifting a standard rule on protecting the identities of under-18s who are in court.

Why have we only been told now of additional charges?

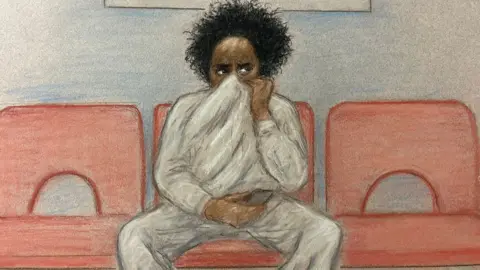

Axel Rudakubana appeared in court on Tuesday to face charges of producing a biological toxin and possession of a document likely be useful in terrorism.

That’s because he was only charged with those new offences the day before.

Both the Conservative Party leadership candidates suggested there were questions to be answered here.

PA Media

PA Media

Robert Jenrick told ITV’s Good Morning Britain that “the state should not be lying to its own citizens”.

He then clarified that he did not know if the state was lying, and added: “We don’t know the reason why this information has been concealed.”

His Tory rival, Kemi Badenoch, said there were “serious questions to be asked” of the police, the Crown Prosecution Service “and also of Keir Starmer’s response”.

This needs breaking down.

The police have publicly said that ricin was found in Axel Rudakubana’s home after it was searched following his arrest.

The fact that we were not told is not surprising because police investigations are always confidential – and their conclusions only become apparent when someone is charged.

It is not unusual – particularly where a defendant is already in custody – for the police and prosecutors to take their time on deciding additional charges.

They will not discuss this publicly because they have a duty not to influence a jury.

Have the police been covering up an act of terrorism?

Axel Rudakubana’s second new charge, the possession of a military study of an al-Qaeda manual, is an allegation under the UK’s main terrorism legislation.

He is charged with possession of a document “likely to be useful to a person committing to or preparing an act of terrorism”.

But making that allegation does not automatically mean there has been an act of terrorism and he has not been charged in relation to any act of terrorism.

To declare a terrorist incident, the police must be sure a suspect had been motivated to use violence in order to influence the government or public in the name of some political, religious, racial or ideological cause.

These decisions can take a long time – sometimes months – because police chiefs don’t want to jump to conclusions and there is often an enormous hunt through social media for evidence to decide the question one way or another.

Have ministers been keeping secrets?

The new charges Axel Rudakubana faces required the consent of the attorney general, the top legal adviser to the government who sits in the cabinet.

The AG’s day-to-day role is to advise the government on how to act lawfully – and he also has to sign off use of some of our most complex criminal laws, including terrorism act offences.

This is a safeguard baked into the law to make sure these prosecutions are only used when absolutely necessary.

It’s a legally confidential process. The decision-making does not involve some kind of vote around the cabinet table. It is not a political decision.

PA Media

PA Media

It is absolutely standard for prime ministers and home secretaries to be briefed on really big ongoing criminal operations.

They may need to take parallel decisions about public safety or find extra help for the police – an example of that being how the military had to get involved in the Salisbury nerve agent poisonings.

Ministers will never talk about these confidential briefings. And the reason why is best illustrated by the Operation Pathway catastrophe blunder of 2009.

The then-head of counter-terrorism was photographed going into Downing Street to brief government on a suspected terror bomb plot.

He was holding a document that revealed the plans – and its disclosure forced the police to completely change their plans.

The last thing the police want is for ministers to be revealing the detail of an operation that may be unfolding – because detectives need to be able to decide for themselves when is the best time to make arrests.

Is the Southport case being delayed?

This has come up on social media – but so far the prosecution has been prioritised through an embattled and backlogged court system, towards a trial date early next year.

Sometimes, when extra charges are added to a case, a judge has to put a case back a bit to give the defence more time to prepare.

They need to be sure that a trial will be fair, comprehensive and not suddenly come unstuck because it’s been rushed.