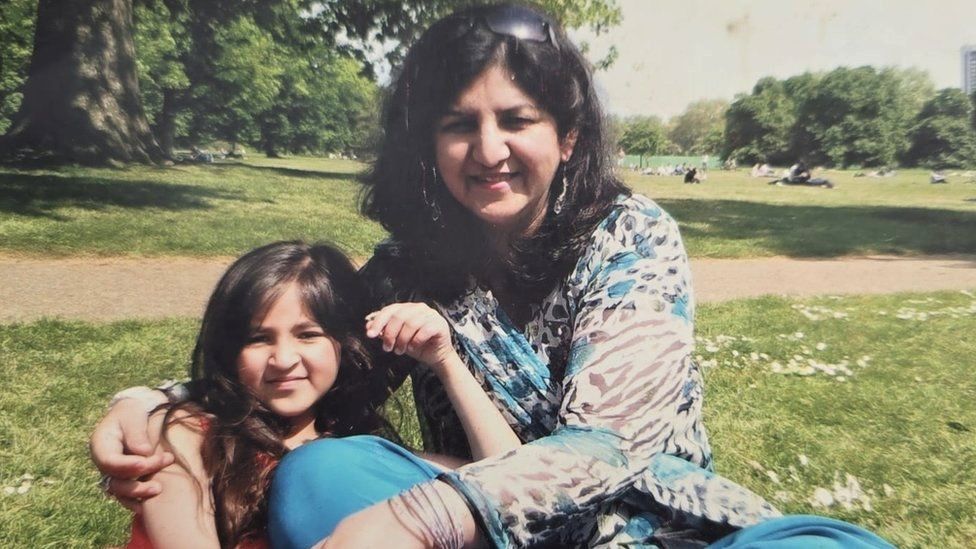

Nafisa Khan, pictured with her daughter in 2010, died after an operation at a Spire Healthcare hospital

By Monika Plaha

BBC Panorama

A woman died when a major private healthcare provider failed to transfer her to NHS intensive care quickly enough after she became critically ill.

Sabrina Khan said Spire Healthcare staff “should have known something was wrong” with her mother, Nafisa.

The BBC also obtained testimony from doctors – contracted by the company to work up to 168 hours a week – who say long hours could put patients at risk.

Spire Healthcare has apologised for failings in Nafisa Khan’s care.

The death of Mrs Khan from east London is one of several deaths following surgery at Spire Healthcare, looked at by BBC Panorama.

Spire Healthcare, which runs 39 private hospitals across the UK, is one of the biggest private hospital chains.

All surgery, wherever it’s carried out, comes with some risk and things can go wrong. Spire has received three Prevention of Future Deaths reports from coroners calling for action in the past two years.

In one case in Norwich, the coroner issued a warning about Spire’s continuing reliance on ambulance transfers to NHS hospitals in the event of emergencies, after three patients had died following long waits.

In England alone, there are more than 6 million people on NHS waiting lists. In some cases the NHS will pay for patients to be treated in private hospitals to help reduce the backlog.

Since 2021, Spire Healthcare has treated more than half a million NHS patients. Last year its profits rose by more than 30% to £126m.

While most NHS hospitals have intensive care units, most private hospitals do not.

Sabrina Khan says her mother’s condition was worsening for hours before she was transferred to an NHS hospital

BBC Panorama has found evidence that some patients treated in Spire hospitals were unaware there were no intensive care facilities.

Dr Nick Woodier at the Health Services Safety Investigations Body said that “there is a risk to patient safety”, particularly where the NHS does not understand the capabilities of a particular private hospital.

Following Panorama’s questions to Spire, the company has now updated its hospital websites, informing patients they may need to be transferred to the NHS for intensive care.

When ambulance staff eventually arrived to take Nafisa Khan to an NHS hospital, daughter Sabrina says Spire Healthcare’s east London hospital had so few staff on duty that the cleaners let them in.

After having been referred to Spire, Mrs Khan underwent a routine gallbladder operation in September 2021. She had been told it would be quicker for the NHS to pay for the procedure to be done privately.

The morning after her surgery, Mrs Khan deteriorated and her condition became critical. Spire has five hospitals with critical care units, but Spire East London does not have one.

Mrs Khan’s family say the ambulance to take her to an NHS hospital did not arrive until about 22:00 that night.

“Why did they wait that whole Saturday while she was deteriorating, while she was vomiting, to transfer her to the NHS hospital?” said Sabrina.

Mrs Khan died shortly after being taken into NHS intensive care.

Dr Nick Woodier, who investigates safety in healthcare, said the NHS is not always aware of private hospitals’ capabilities

Spire Healthcare has admitted it failed to fully appreciate the seriousness of Mrs Khan’s deteriorating condition and has apologised.

It said she should have been transferred earlier to an NHS hospital for critical care.

In 2023, Spire Healthcare was warned about another death as part of a coroner’s Prevention of Future Deaths report. These are issued when someone has died and action needs to be taken to reduce the risk of further deaths occurring in the future.

At another Spire Hospital, in Leeds, a woman had developed sepsis – a life-threatening reaction to an infection – after a routine hernia operation.

The hospital was late in identifying the complications and the woman died. The coroner concluded her death had been avoidable and highlighted the role of the on-call doctor, known as the resident medical officer (RMO).

“The RMO was called twice during the night but failed to appreciate that the deterioration in her condition necessitated an escalation to the surgeon or anaesthetist,” the coroner said.

Resident medical officers, now called resident doctors, provide 24-hour cover at private hospitals. In some private hospitals, including Spire, these doctors are contracted to work up to 168 hours a week.

With more than six million people in England alone waiting for an operation on the NHS, Monika Plaha investigates patient safety at one of the UK’s biggest private healthcare providers.

This may mean they work from 09:00 to 17:00 and then are on call until the following morning, when they work a day shift again and then repeat the pattern across a week.

Since 2009, the NHS has said its doctors should not work on average more than 48 hours a week.

Panorama has obtained the testimony of 28 resident medical officers who worked at Spire until 2022 and who want to remain anonymous. Almost all of them expressed concern about their workload and the potential safety implications for patients.

One said: “I was working round the clock, being the only doctor at night. Feeling constantly burnt out. And this obviously is not safe for the patients, nor for me as a doctor.”

“I constantly had concerns about patient safety in the Spire hospital,” said another.

Spire Healthcare has received three Prevention of Future Deaths reports following post operative emergencies

Spire Healthcare told Panorama the wellbeing of all its staff is of “paramount importance” and said it has since updated its working practices.

The company said it has “robust safeguards to ensure that resident doctors are well supported” and are “only working when adequately rested”.

Spire Healthcare was previously caught up in a major medical scandal when rogue surgeon Ian Paterson – who worked mostly in the NHS as well as for Spire – was jailed in 2017 for carrying out more than 1,000 unnecessary operations on women.

Then in 2018, another Spire surgeon, Michael Walsh, was suspended after dozens of patients complained about him. Spire referred Walsh to the regulator, the General Medical Council. Walsh denied any wrongdoing and later took himself off the medical register before his case was completed.

After three deaths in less than a year at the Spire Norwich Hospital, a coroner raised concerns about the company relying on NHS ambulance services in the event of medical emergencies.

In 2022, Geoffrey Hoad, 85, was in severe pain and needed a hip replacement. He decided to pay for surgery at Spire Norwich because of the two-year NHS waiting list.

Image source, ANNE MCDOWELL

Anne McDowell says she had no idea Spire Norwich had no intensive care facilities before husband Geoffrey Hoad went in for his operation

The operation appeared to go well. Mr Hoad had diabetes and coronary artery disease. Though he was a higher-risk patient, Spire says he was well enough to be treated at its hospital.

Over the next couple of days his condition deteriorated.

His wife, Anne McDowell, said she had “no idea at all” that the hospital did not have its own intensive care unit. An ambulance to take him just a mile down the road to the Norwich and Norfolk University Hospitals NHS Trust took 14 hours to arrive.

After he was eventually transferred to the NHS, Mr Hoad suffered a heart attack. The consultant told Ms McDowell her husband would not recover.

At an inquest last September, while the coroner didn’t say the delay had contributed to Mr Hoad’s death, she did issue a Prevention of Future Deaths report. She found that by continuing to rely on the NHS ambulance service, Spire had not learned the lessons from Mr Hoad’s death and two previous deaths.

In 2021, two patients undergoing routine operations at Spire Norwich died after their conditions deteriorated. They also faced long ambulance delays to transfer them to the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Trust.

East of England Ambulance service has apologised to the three families for the delayed transfers. It said response times have improved significantly since these tragic cases.

Spire Healthcare said transferring patients after operations is “an extremely rare occurrence, and long delays are even rarer”.

It said it continues to “work closely with the ambulance service and local NHS trusts on ways to ease delays”.

The company said that “ensuring patients are safe is at the heart” of what it does, and that 98% of its hospitals are rated “good” or “outstanding”.

The Department of Health and Social Care says since the Paterson Inquiry “key actions have been taken to strengthen protections for patients receiving care from independent sector providers”.