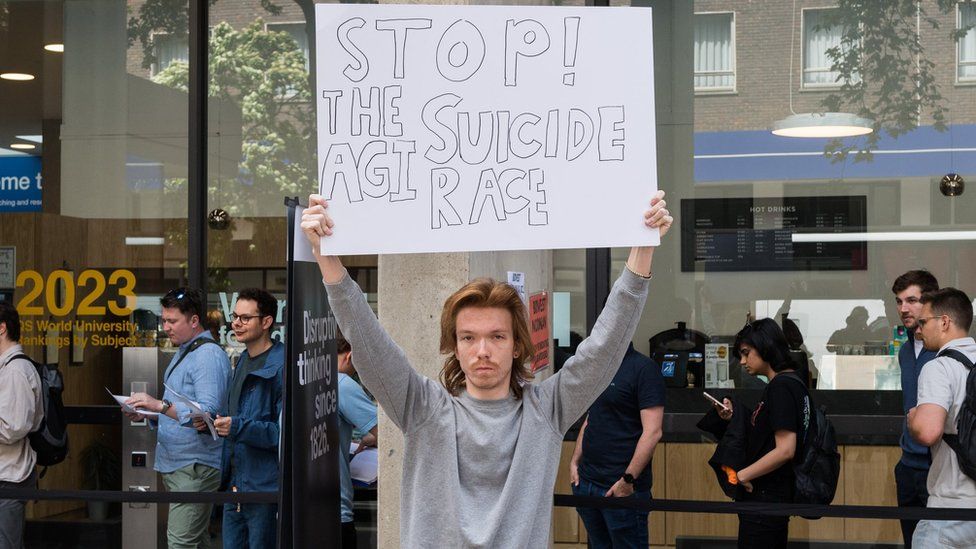

A protester calling for the AI race to be stopped

By Tom Singleton

Technology reporter

A major tech company, which has just announced extra UK investment, has rejected calls to pause the development of artificial intelligence (AI).

Fears about the technology have led to demands for new regulation, with the UK calling a global summit this autumn.

But the boss of software firm Palantir, Alex Carp, said it was only those with “no products” who wanted a pause.

“The race is on – the only question is do we stay ahead or do we cede the lead?” he told the BBC.

Mr Carp told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme the West currently held key commercial and military advantages in AI – and should not relinquish them.

“It’s not like if we slow down, the AI race will stop. Every country in the world – especially our adversaries – cannot afford for us to have this advantage,” he said.

“Studying this and allowing other people to win both on commercial areas and on the battlefield is a really bad strategy.”

Mr Carp’s comments strike a very different tone to the recent glut of dire warnings about the potentially existential threat AI poses to humanity – and accompanying calls for its development to be slowed or even halted.

Regulators worldwide are scrambling to devise new rules to contain its risk.

The government says the UK will host a global AI summit this autumn, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak saying he wanted the UK to lead efforts to ensure the benefits of AI were “harnessed for the good of humanity”.

It is not yet known who will attend the summit but the government said it would “bring together key countries, leading tech companies and researchers to agree safety measures to evaluate and monitor the most significant risks from AI”.

Mr Sunak, currently meeting US President Joe Biden in Washington DC, said the UK was the “natural place” to lead the conversation on AI.

Downing Street cited the prime minister’s recent meetings with the bosses of leading AI firms as evidence of this. It also pointed to the 50,000 people employed in the sector, which it said was worth £3.7bn to the UK.

‘Too ambitious’

However, some have questioned the UK’s leadership credentials in the field.

Yasmin Afina, research fellow at Chatham House’s Digital Society Initiative, said she did not think that the UK “could realistically be too ambitious”.

She said there were “stark differences in governance and regulatory approaches” between the EU and US which the UK would struggle to reconcile, and a number of existing global initiatives, including the UN’s Global Digital Compact, which had “stronger foundational bases already”.

Ms Afina added that none of the world’s most pioneering AI firms was based in the UK.

“Instead of trying to play a role that would be too ambitious for the UK and risks alienating it, the UK should perhaps focus on promoting responsible behaviour in the research, development and deployment of these technologies,” she told the BBC.

Deep unease

Interest in AI has mushroomed since chatbot ChatGPT burst on to the scene last November, amazing people with its ability to answer complex questions in a human-sounding way.

It can do that because of the incredible computational power AI systems possess, which has caused deep unease.

Two of the three so-called godfathers of AI – Geoffrey Hinton and Prof Yoshua Bengio – have been among those to sound warnings about how the technology they have helped create has a huge potential for causing harm.

In May, AI industry leaders – including the heads of OpenAI and Google Deepmind – warned AI could lead to the extinction of humanity.

They gave examples, including AI potentially being used to develop a new generation of chemical weapons.

Those warnings have accelerated demands for effective regulation of AI, although many questions remain over what that would look like and how it would be enforced.

Regulatory race

The European Union is formulating an Artificial Intelligence Act, but has acknowledged that even in a best-case scenario it will take two-and-a-half years to come into effect.

EU tech chief Margrethe Vestager said last month that would be “way too late” and said it was working on a voluntary code for the sector with the US, which they hoped could be drawn up within weeks.

China has also taken a leading role in drawing up AI regulations, including proposals that companies must notify users whenever an AI algorithm is being used.

The UK government set out its thoughts in March in a White Paper, which was criticised for having “significant gaps.”

Marc Warner, a member of the government’s AI Council, has pointed to a tougher approach, however, telling the BBC some of the most advanced forms of AI may eventually have to be banned.

Matt O’Shaughnessy, visiting fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said there was little the UK could do about the fact that others were leading the charge on AI regulation – but said it could still have an important role.

“The EU and China are both large markets that have proposed consequential regulatory schemes for AI – without either of those factors, the UK will struggle to be as influential,” he said.

But he added the UK was an “academic and commercial hub”, with institutions that were “well-known for their work on responsible AI”.

“Those all make it a serious player in the global discussion about AI,” he told the BBC.