By Marco Silva & Maryam Ahmed

BBC Verify

Earlier this year, TikTok vowed to clamp down on climate change denial. But a BBC investigation tracked one video that has been viewed millions of times – and found the company is struggling to stop false climate information from spreading across the platform.

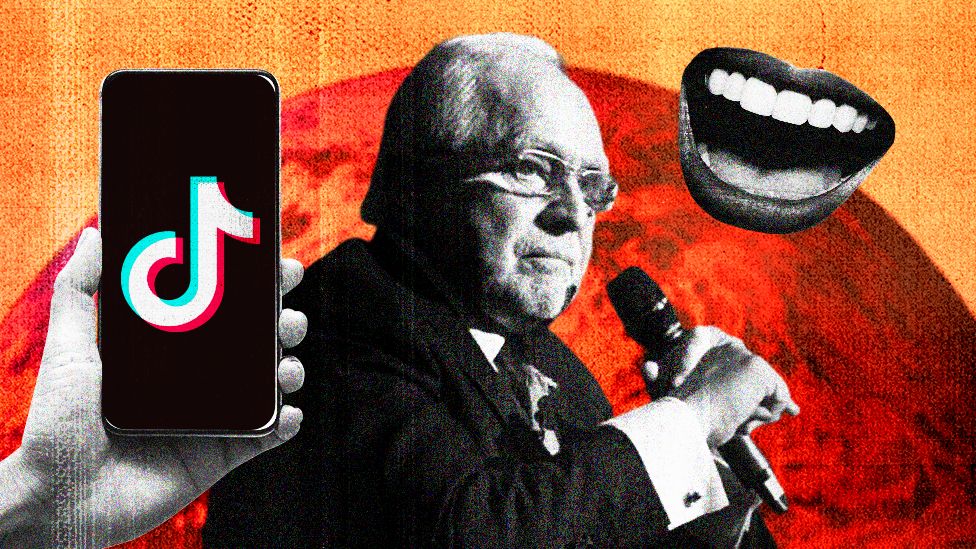

If you searched for “climate change” on TikTok in recent months, you might have come across a video featuring Dan Peña, a self-styled “business success coach” with thousands of followers on social media.

The video, shot during the 2017 London premiere of a documentary film about Mr Peña, shows a heated exchange between the American businessman and a member of the audience.

Asked what “the people with the money” will do about climate change, he replies: “The financial institutions and the banks know [climate change] is not going to happen.”

He adds, without providing any credible evidence: “It’s the greatest fraud that has been perpetrated on mankind this century.”

Contacted by the BBC, Mr Peña stood by these comments, saying climate change was actually a “historical norm” over thousands of years and “not new”. He questioned whether it was a “genuine threat” as well as the effectiveness of measures proposed by climate change activists in the face of growing emissions from China.

The overwhelming weight of scientific evidence has found that world temperatures are rising because of human activity, leading to rapid climate change and threatening every aspect of human life.

But while Mr Peña’s statements conflict with that scientific evidence, this clip appears to have been edited and re-uploaded by other users from different TikTok accounts dozens of times, racking up more than nine million views in the process.

Under new community guidelines unveiled by TikTok last April, content that “undermines well-established scientific consensus” on climate change will not be allowed on the platform.

And yet, the clip depicting Mr Peña is far from an isolated occurrence: the BBC identified 365 different videos in English denying the existence of man-made climate change.

The BBC reported hundreds of videos like these, making false statements about climate change

TikTok itself deems climate change denial to be “harmful misinformation”. Using tools available to any TikTok user, we reported those videos to the platform under that category. We then waited for at least a day to find out whether they would be taken down.

The company did not remove almost 95% of the posts we flagged up – videos that, having been watched almost 30 million times, appeared to be attracting significant attention.

In a statement to the BBC, TikTok said it is working “to empower informed climate discussions”, and that it is working with fact-checkers to tackle misinformation.

The company also pointed out that, when users search for videos about climate change, they are being shown a link to a United Nations website on the topic.

But the video of Mr Peña demonstrates how “bad arguments can spread really fast on TikTok”, says Roshan Salgado D’Arcy, a science communicator who uses social media to debunk viral videos that contain false claims about climate change.

“There are no real checks and balances to make sure that the information is accurate.”

Roshan Salgado D’Arcy says false information about climate change is still “really prevalent” on TikTok

The problem is not exclusive to English-speaking TikTok either: BBC Monitoring found dozens of other climate change-denying videos in Spanish, Turkish, Arabic, Portuguese, and Russian.

“As a member of the public on social media, it must be very easy to get the wrong idea about how certain we are about climate change,” says Dr Doug McNeall, a scientist from the Met Office’s Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research.

“Misinformation can really damage our discussion about what to do about climate change.”

TikTok is aware of the problem – which is why, to mark Earth month in April, it announced it would begin actively removing content that contradicts basic climate science.

In a blog post published at the time, it listed as examples of rule-breaking content posts “denying the existence of climate change or the factors that contribute to it”.

But the reach of videos like those featuring Mr Peña raises questions about how successfully this new policy is being enforced.

“Rules become irrelevant, if they’re not applied consistently, accurately and fairly,” says Jennie King, head of climate research and policy at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a UK counter-extremism think tank.

Ms King said this emboldens people to try “to game the system even more, because they know they can ultimately act with impunity”.

Paul Scully MP, the minister for technology and the digital economy, told the BBC that the government’s proposed Online Safety Bill would guarantee that the responsibility of social media platforms to tackle disinformation was “taken seriously”.

Jennie King says TikTok’s focus on content removal is “not only potentially unconstructive, but practically unenforceable”

After we shared the findings of our investigation with TikTok, 65 accounts that had been posting wrong information about climate change in breach of the platform’s guidelines were permanently removed.

The company also removed most of the remaining videos that were still online – including several that featured Dan Peña’s 2017 talk.

However, at the time of writing, several copies of the clip featuring Dan Peña describing climate change as the “greatest fraud” can still be found on the app.

At the Met Office, Dr McNeall welcomes TikTok’s efforts against misinformation, but he questions whether this is a battle the company can win.

“As a scientist I’m happy to be challenged,” he says.

“Maybe we should focus on promoting good climate science information, rather than just removing the content that we perhaps don’t like.”