Caroline Brouwer had barely walked out of the job interview before the argument began behind her.

“One of the coaches was very old school and very, very anti having a woman on the team,” she remembers.

“I could hear the argument as I left. One said, ‘Who the hell else are we going to get? There is nobody in the area and we have got to have someone.'”

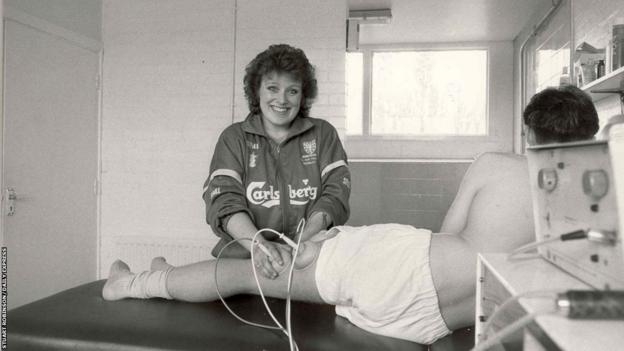

The vacancy was for an assistant physio and Brouwer, as the candidate, was perfectly qualified.

But, the date was December 1981 and the club was Wimbledon – a time and workplace quite different from today.

Unbeknown to Brouwer, then 22, she had applied to be part of a dressing room that would become the most storied in English football – a buoyant mix of brutality and camaraderie that would rise to the top of the game.

After her interview, Brouwer returned home to her parents’ house in Surrey and waited as Wimbledon’s hierarchy mulled over whether to make an offer.

A letter landed on the doormat.

“They took me on,” Brouwer remembers.

In turn, it wasn’t long before Brouwer realised exactly what she had taken on.

Brouwer’s father Thom wasn’t a fan of Wimbledon. Or any English football.

He had come to England from the Netherlands to pursue his engineering career.

In his time off, he followed the game back home, rather than the one on his doorstep.

“He was an Ajax fan,” says Brouwer.

“From when I was tiny I remember him sitting with Dutch newspapers, listening to Dutch radio, reading the Voetbal International magazines that his sister in the Hague had sent over.

“He thought English football was crude in comparison to the Dutch game – bear in mind he was an Ajax fan at the height of Total Football.”

He passed on his passion, though. Caroline, the oldest of his three children, would fly into tackles in local kickabouts, bruising the shins and pride of local boys.

When she was 11, she went down to nearby club Leatherhead. She didn’t play. Opportunities were few for young girls in the early 1970s.

Instead, she volunteered, serving in the tea bar, sweeping terraces and painting goalposts.

By 14, she was travelling on the team coach to away matches.

The team physio – John Deary – shared those journeys and spotted potential. Brouwer was a grammar school girl, studying A Levels, but with no interest in going to university. The Football Association’s Treatment of Injury course – a three-year undertaking at the FA’s rambling country house base of Lilleshall – might suit her, he suggested.

It did. A few months after finishing her course, Wimbledon invited Brouwer to that job interview. Even if some of the panel, had they known her identity, would have rejected her out of hand.

“I went in for the first time between Christmas and New Year. That was a moment of ‘oh my goodness they are not really as nice as the Leatherhead boys’,” Brouwer says.

“It was a baptism of fire. It was like a male St Trinian’s.”

Brouwer stresses that her experience of becoming part of the Wimbledon inner sanctum wasn’t any worse for being one of the few women working in men’s football.

But it didn’t help either.

“I just developed the hide of a rhino,” she says. “They would try and shock you.

“There was one instance, during the time when Don Howe was coaching us, when one of the players starting playing with himself, while I was massaging him.

“I just walked off and said ‘you need a hooker, not a physio.’

“Don whispered in my ear, ‘Nice one, you handled that well’. He was a gentleman.

“But some of the players…you just had to ignore them. If you ignored them they wouldn’t get the attention they crave.”

Wimbledon were difficult to ignore.

When Brouwer joined in December 1981, they were fighting, in vain, against relegation to the fourth tier of English football.

Over the following five seasons, however, they were promoted three times, slicing through the Football League into the upper reaches of the top flight.

There were three parts to their rise.

Tactically, they were efficient and effective, with video analyst Vince Craven pulling in footage from around the world to refine a direct style, as manager Dave Bassett drilled players on the patterns and positions to take up in every scenario.

Emotionally, some thrived in a dressing-room atmosphere that Brouwer admits others found “quite toxic”, bonding tight against outsiders.

And physically, Brouwer saw close up how hard the team worked

“We had a training ground near the bottom of the A3 in London, near the Robin Hood roundabout,” she says.

“There were several runs: the A3, the Windmill, the Richmond Park – that last one was about seven miles.

“The coaches used to throw in runs throughout the season, and because [youth-team coach and assistant manager] Geoff Taylor was ex Royal Signals, we had contacts in the Army. The team would do the assault course and training there.

“People thought Wimbledon mucked around. And they did, but when it came time to work, they worked bloody hard.

“Someone would be throwing stuff round the dressing room, someone would be in a headlock, someone would be on the phone to the bookies, but then there was an absolute, instant switch from mayhem to discipline.

“They were supremely fit, well drilled and knew their jobs. I don’t think they get the credit they deserve.

“We had some very good players over the years, which was proven by the number of them who moved on to bigger clubs and got international call-ups.”

Brouwer says she was a “small cog” in Wimbledon’s rise, but she also helped in a way no-one else could.

“In those days, there wasn’t any provision for mental health,” she says.

“It was a hard atmosphere. You were not allowed to show weakness, you had to be strong the whole time – and people weren’t.”

Players cut out of the team’s plans by long-term injuries could, and did, slip into depression. Brouwer would take them through their treatment, away from the rest of the group, giving them space to talk and a structure to stay busy.

“I don’t think the managers appreciated that, having a woman there in the background, how much players talked to me,” she adds. “I was a sounding board for them.

“It was all done very low key, though, they didn’t want to show weakness or lose their place.”

The peak of Wimbledon’s rise came 35 years ago, when they took on an all-conquering Liverpool in the 1988 FA Cup final.

The contrast in the teams’ styles and pedigrees was memorably summed up by commentator John Motson characterising Wimbledon as the Crazy Gang and Liverpool as the Culture Club.

Some saw beauty in the Dons’ fairytale. The team and their partners appeared on a cheery episode of The Clothes Show in the run-up to their Wembley trip as Top Man chief executive and future Leeds chairman Peter Ridsdale helped the players pick out their cup final suits and manager Bobby Gould talked about family values.

Others could only see the beast.

“Does anybody like Wimbledon outside their small but loyal support? It’s hard to believe,” wrote journalist Brian Glanville in the Sunday Times.

“When one has paid tribute to their ability to turn such dross into gold, a major question remains. If they win at Wembley, what will it do to English football?”

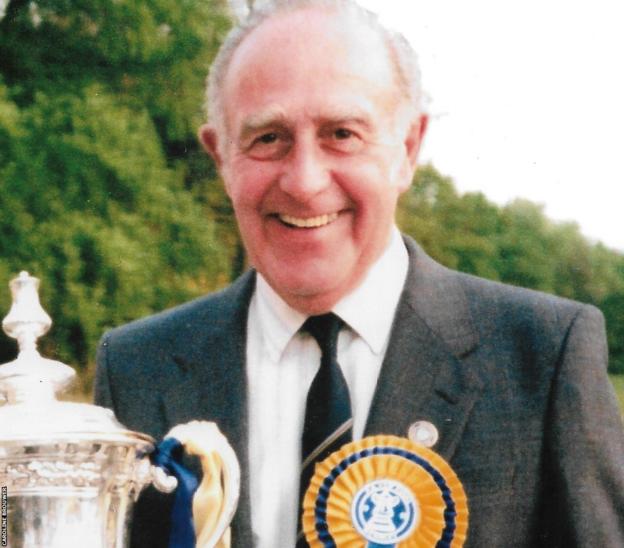

Brouwer, one of only five people at the club, along with two kit men, goalkeeper Dave Beasant and striker Alan Cork, to have been present for the entirety of the rise from the Fourth Division to Cup final, was treated as an entertaining side note.

One newspaper took her out for a long, leisurely lunch at a swish hotel on London’s Strand. She spoke about her work and the team for two and a half hours.

The subsequent story ignored it all, instead focusing on a one-off prank where she, along with the rest of the backroom staff and the club’s octogenarian chairman, was thrown in the team bath.

“I wasn’t known, and I didn’t want to be known,” she remembers.

“I did the occasional interview, But mostly I dreaded it.

“I think I would have got more attention, in the very shallow way that newspapers were in those days, if I was tall, blonde and leggy. I wasn’t. I was a short, fat, brunette.

“I was not glamourous enough for the attention. And it suited me. I just wanted to do a good job, get injured players back onto the pitch and have fun being part of the team.”

And no day was more fun than 14 May 1988.

In their two league meetings with Liverpool, Wimbledon had suffered a narrow 2-1 defeat at Anfield and taken a point from a draw at Plough Lane.

The gap between the sides was small. Some in the dressing room backed their physicality, hunger and aggression to close it.

“It was absolutely intense,” remembers Brouwer of the dressing-room atmosphere as kick-off approached.

“We had players who could handle themselves and we had a couple who were over the top. Gouldy needed to calm them down and get their minds on the game.

“But they were not intimidated and believed they could win. That was the thing.”

Midway though the first half, Vinnie Jones, Wimbledon’s midfield enforcer, clattered though opposite number Steve McMahon. McMahon was straight to his feet, but the tone was set.

“It was quite physical, people were being caught and Liverpool were putting it about – Steve McMahon was not averse to putting an elbow in,” remembers Brouwer.

“Vinnie got a cut, although it didn’t bleed too much.”

The conditions, as much as any injuries inflicted by the opposition, turned out to be Brouwer’s main concern, though.

Towards the end of the first half, Howe, who had been part of Bobby Robson’s England staff at Mexico 1986, called on her to enact a plan they had for an unusually hot day at Wembley.

With two kitmen, she ran back to the dressing room and threw ice and towels into a cold bath. As Wimbledon’s players trooped in with a 1-0 lead, they draped the towels over their shoulders to reduce their core temperature.

When they returned later with the match finished, the score unchanged and the FA Cup secured, the depths they had dug for the silverware were clear.

“I took some snaps with an Instamatic camera, and in lots of them the players are just lying on the dressing room floor,” Brouwer remembers

“They were exhausted, running just on adrenaline and initially they were drained.”

A few drained bottles later though and they were restored.

“The Wembley staff were trying to kick us out by the end. Apparently we stayed longer in the dressing room than any other winning team had done,” says Brouwer

“There was lots of champagne, pictures with the cup. People just didn’t want to leave, they just wanted to enjoy it.”

Eventually Wimbledon piled back on the team coach. Offered a night out at a cabaret club in central London, the squad instead chose a marquee on the Plough Lane pitch for their celebrations. It turned out the Crazy Gang’s party was so good, some of the Culture Club joined in.

“You had people turning up who were friends of friends,” remembers Brouwer.

“June Whitfield was the chairman of our supporters club and some of her actor friends were there. One of the directors brought in some dancers from the Royal Ballet.

“Occasionally you would look round and think ‘who the hell are you and what are you doing at our party?’ But it was nice.”

Even Brouwer’s father Thom, long since reconciled to Wimbledon’s playing style, was there to join in, with Brouwer’s mother Jane.

“Everyone who was close to you could be involved, that was the Wimbledon way, it was very inclusive.”

Brouwer left Wimbledon in 1994 and football entirely in 2000 after subsequent spells with Dulwich Hamlet and Hendon. But she still makes the journey to Plough Lane from time to time.

“I just go there, buy my ticket, watch the game, and come out. I don’t court any favours,” she says.

There was a moment from a couple of season ago that sticks with her.

“I saw a game against Oxford United and they had a female physio,” remembers Brouwer. “When she ran on the pitch, there wasn’t a murmur. None of the ‘give us a rub down darling’ and all the rubbish that I used to hear from the terraces.

“There was not one sound, she just went on the pitch, she did her job and she went off again. As she walked down by the goal, not one idiot said anything. That is huge step forward.”

When Brouwer looked over at the Wimbledon bench this season, it was another woman – Deanne Goring – following in her footsteps, holding the physio’s bag.

Goring’s recruitment process will have been very different from Brouwer’s. Her experience in the dressing room will be too.

But, while much has changed, some memories are indelible, some things stay for good.

“Football has given me confidence in any situation,” Brouwer says.

“I don’t get fazed by television appearances, interviews or public speaking.

“And, when I think back, that day was just amazing. I had been to so many Wembley cup finals over the years, but to stand at the bottom of the steps, below the Royal Box and watch your mate lift the cup… that’s just lovely.”