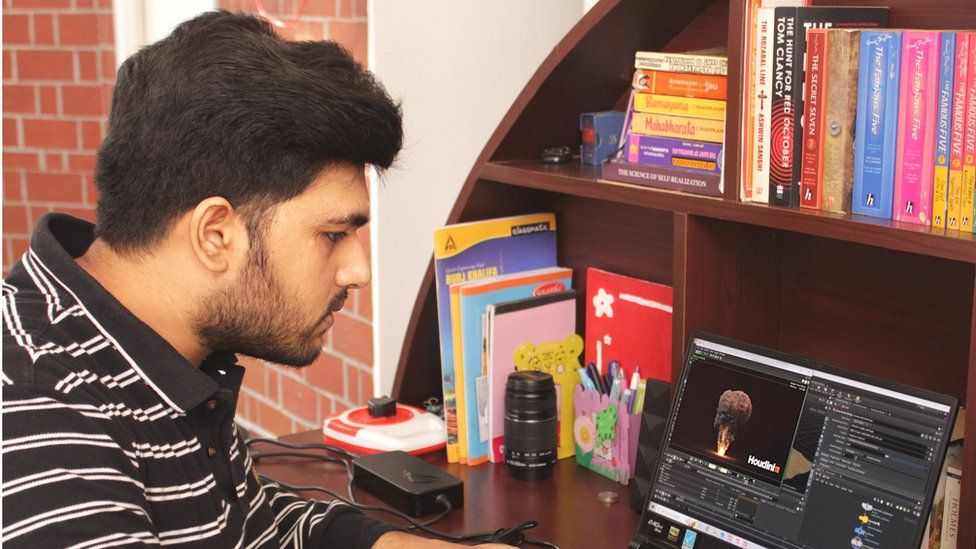

Vinay Sastha R has just started out in the visual effects industry

As a child, Vinay Sastha R found his imagination fired by films like The Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series.

But unlike most other people, he now works on movies. Based in Trichy in southern India, Mr Sastha R works as a technical director creating visual effects (VFX) for DNEG, one of India’s leading VFX studios.

Aged 26, he only has a couple of years in the industry, but still gets to work on fun projects.

“A technical director mainly deals with creating elements that could not be made while filming… like creating a lava rain in a city, making rain freeze in air, or the moon melting – anything fantastical you can think of,” he says.

“I love and enjoy what I am doing.”

Mr Sastha R has benefited from a boom in India’s VFX industry. Not only is India’s domestic film industry demanding more special effects, companies from overseas are sending work to India.

For example, the dragons in the fifth season of Game of Thrones were created in Mumbai.

Image source, HBO

The dragons in season five of Game of Thrones were created in India

Streaming entertainment firms like Netflix, animated TV and film producers, and the computer games industry are all demanding more.

“The VFX industry has surged due to an infusion of visual effects in almost all the entertainment sector,” says Namit Malhotra, founder of Prime Focus, a giant Indian media firm which owns DNEG.

India is a relatively cheap place to create such artwork and the adoption of cloud computing has made it easy for Indian workers to contribute to projects based overseas.

“India has become a big market for outsourcing though not the entire movie – but parts of movies,” says Ketan Mehta, founder of Cosmos Maya, a visual effects and animation studio.

He says it’s “only a matter of time” before Indian studios are handling all the visual effects for big global productions.

But being plugged into the global market has its downside. India could not dodge the effects of the strikes in Hollywood, which shut down TV and film production for months last year.

“The strike in Hollywood had a big impact on the Indian market. We could clearly see the ripple effects. There were layoffs and production houses downsized. A number of projects have got delayed and still the market is extremely slow with the Hollywood work coming in,” says Mr Mehta.

Nevertheless he is confident the market will recover. And the next challenge for the Indian industry could be finding enough staff.

At the moment around 250,000 people work in the VFX and animation industry, according to the Animation, Visual Effects, Gaming and Comic (AVGC) Task Force.

But it estimates that by 2032 that number will have ballooned to 2.2 million.

Image source, Prime Focus

The visual effects industry wants more young people with the right skills

To help supply those workers, the AVGC is working with universities and colleges to come up with courses and qualifications.

Ashish Kulkarni, a member of the AVGC Task Force, would like to see senior members of the industry get involved in education.

“The child who has taken up this course should be motivated by well know people in the industry, so VFX and animation becomes popular, and parents are not reluctant to let children pick this field,” he says.

Kshitiz Sharma, from the School of Film Making at Whistling Woods International, says India has plenty of young people with technical skills like engineering.

What is lacking, he says, are courses which teach a “deep understanding” of film-making and the artistic side of visual effects.

But that shortfall is being aided by new VFX courses offered by universities and other institutions.

“The future is promising for people who want to get in to animation and VFX,” says Mr Sharma.

While India has, for the last two years, had the fastest economic growth of any major economy, it is still at the lower end of the middle-income countries.

So it might not be easy to find the money for visual effects courses and the expensive hardware and software needed for training.

“VFX and animation courses are not easy on pocket. So, if we want to become the global hub, we should pay attention to the cost factor,” says Mr Sharma.

He points out that it can cost thousands of dollars a year just to use some software packages used in creating visual effects.

His solution is to get big media and tech companies to shoulder more of the cost.

“It’s not just the government’s job to provide grants. Corporates should come forward to find a reasonable solution to provide the tools and technology on the educational level.”

“Software should be available to students for educational purposes,” says Mr Sharma.

Image source, Red Chillies Entertainment

AI will be an important tool for visual effects producers

Artificial intelligence (AI) may help ease the staff shortage in the industry.

It has already “changed the way films are made” according to Keitan Yadav a VFX producer and chief operating officer at Mumbai-based Red Chillies Entertainment.

“If I have to show a director a shot, I can create a scene with the help of AI – changes can be made without losing time,” he says.

“Complex VFX-heavy scenes are using AI to quickly generate low resolution CGI [computer generated imagery] backgrounds, characters, effects simulations and camera motion. Within hours, not months, the final product can be seen and changes can be decided.”

He thinks jobs will be lost as AI takes over in some areas, but other opportunities will arise.

“AI should be viewed as a powerful tool to enhance creativity, productive and quality rather than threat. It’s simple – if 10 doors close, 100 will open.”

Back in Trichy, one of the big thrills of being in the movie industry for Mr Sastha R is simple and low-tech.

“Staying in dark in a theatre, after most of the crowd leaves, and waiting to see your name rolling in the credits. It feels good!”