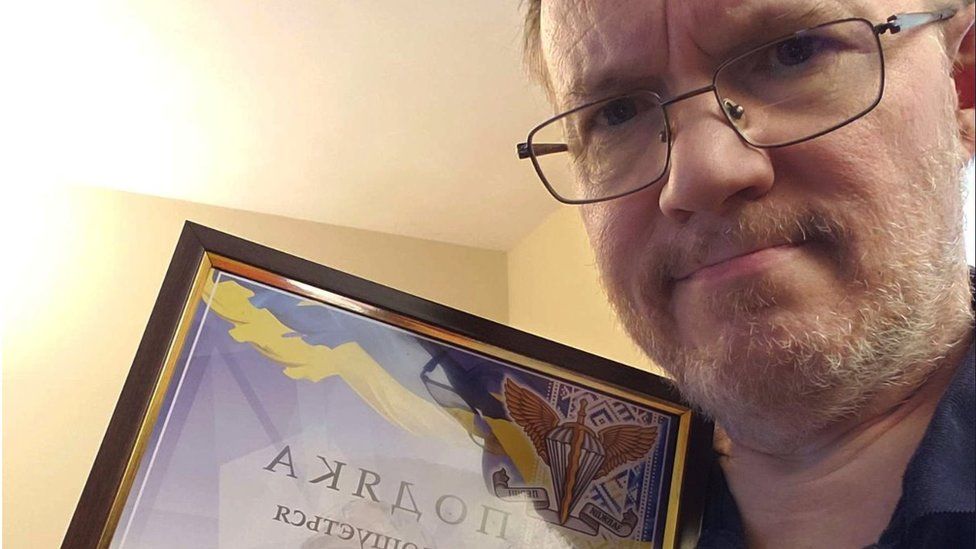

American Kristopher Kortright, known as “Voltage”, has been launching hacking operations against Russia since the invasion

A team of vigilante hackers carrying out cyber-attacks against Russia has been sent awards of gratitude by Ukraine’s military.

The team, One Fist, has stolen data from Russian military firms and hacked cameras to spy on troops.

The certificates are a controversial sign of how modern warfare is shifting.

Concerns have been raised about the practice of states encouraging civilian hackers.

One of the hackers called “Voltage” has been co-ordinating hacks from his home in the US.

His real name is Kristopher Kortright and he is an IT worker from Michigan.

The 53-year-old told the BBC he is delighted his efforts for Ukraine have been officially recognised with a certificate of gratitude.

One Fist is made up of hackers from eight different countries including the UK, US and Poland. They have collectively launched dozens of cyber-attacks – celebrating each one on social media.

The certificates were sent to them all for “a significant contribution to the development and maintenance of vital activities of the military”. They were signed by the commander of the Airborne Assault Forces of Ukraine.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence did not respond to the BBC’s request for comment.

Since the start of the conflict, Ukraine has controversially been encouraging volunteer hackers to attack Russian targets. But sending out official awards to foreign civilians is being seen as a controversial move and a sign of the times.

Although many nations, including the UK and the US, have official award systems for ethical hacking, this is thought to be the first time a country has awarded hackers for malicious and possibly criminal hacks.

In October, in response to the increase in vigilante hacking in Ukraine and in the Gaza conflict, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) warned against the use and encouragement of civilian hackers. It published guidelines to reinforce the ethos of the rules of war laid out in the existing Geneva Conventions.

A member of a Polish vigilante hacking gang called Squad 303 which has also carried out attacks on Russia

Dr Lukasz Olejnik, author of Philosophy of Cyber-security, said Ukraine’s awards to foreign hackers are potentially problematic.

“Giving out awards may further blur the lines between combatants and civilians, and even undermine the recent call by the ICRC to limit and end the involvement of civilians in combat operations. In the long run, such an erosion is dangerous,” he said.

Dr Olejnik also said it is a “testament of our times” that cyber is now considered as a domain of operations and that anyone can join the fight online.

Kristopher started hacking Russia when it launched the full-scale invasion in February 2022, and says he has devoted himself to the cause and sacrificed a lot.

“I’ve lost my job doing this and spent all my life savings in pursuit of a victory for Ukraine,” he said from his home office. “This award is a real morale-booster,” he said.

The awards do not state which cyber-attacks were most useful, but Voltage has three in mind as the most likely candidates.

At the start of the invasion in 2022, One Fist spent months mapping out the physical and cyber-locations of hundreds of publicly viewable CCTV cameras in Ukraine. It was discovered that Russian forces were using them to monitor troops, so his team helped get the cameras switched off.

Conversely, it was One Fist that hacked into cameras in occupied Crimea to catalogue Russian tanks and equipment being moved over the Kerch bridge.

One Fist hacked cameras to allow Ukraine to watch Russian equipment transport

And most recently, in January, Kristopher and others also successfully hacked into a prominent Russian weapons-maker and stole 100 gigabytes of private data, which led to a public celebration from the Ukrainian authorities.

“The array of information transferred to the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine contains drawings, specifications, patents, software referring to both existing and promising military developments,” the announcement said.

Ukraine added that the data stolen was a “significant blow” to Moscow and worth $1.5bn (£1.2bn) – although it did not say how this figure was reached

The Ukraine conflict prompted a surge of cyber-activity – mostly from supporters of Ukraine. Groups like the Anonymous collective targeted Russia with disruptive and low-level hacks that Russia largely brushed off.

In some instances, TV and radio stations were hijacked and news websites defaced.

Russian authorities too have been accused of working with vigilante hacking groups like Killnet to attack Ukraine, but has never admitted having any relationship to the gangs.

Killnet’s leader denies working with Russian authorities on hacks against Ukraine

Most of the vigilante hacking activity on both sides dissipated after the first year as the war ground on. But One Fist has kept attacking Russia and increasingly worked closely with the Ukrainian forces on choosing targets.

Emily Taylor, chief executive of Oxford Information Labs and editor of Chatham House Cyber Policy journal, agrees that the hacking awards are a landmark moment that might shift thinking about how cyber volunteers are used in conflicts.

“Governments usually discourage non-state actors from taking direct action in the cyber-domain, for fear of escalation or unintended consequences, but wartime is often a period of extraordinary technological innovation, and the Ukraine invasion is no exception,” she said.

“Sometimes these events force a reconsideration of issues that have previously been taboo.”

Kristopher says his team has built up a strong relationship with the Ukrainian military. “They send us ideas and we send them options but they don’t ever give us any help or funding as I think that would cross some sort of line,” he said.

Kristopher recognises that receiving military awards is controversial, but is determined to keep hacking for Ukraine.