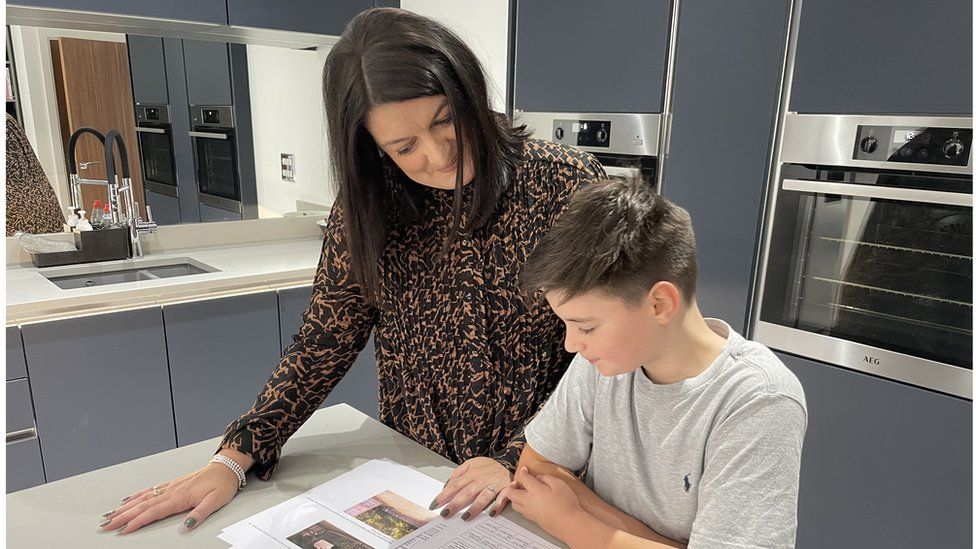

Amanda and Elliott look through his diary each week to find out when he is going into school and when he has to study at home

By Hazel Shearing & Susie Rack

BBC News

Eleven-year-old Elliott was excited about moving up to secondary school this year. He was out meeting another child, who was also due to start at the same Durham school, when the government announced that school buildings constructed with a particular type of concrete had to close immediately.

Elliott has not had much chance to speak to his new friend since then, nor to any of his other classmates – because his school was one of those impacted by the announcement.

St Leonard’s Catholic School was told it could not fully open at the start of term, due to the presence of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac) on the school site.

Instead of going to school, Elliott has spent most of this term doing six hours a day of online lessons, from home, on his mother’s laptop. There are more than 150 other children logged on to the online lesson on his screen – but no-one turns their cameras on, and only the teacher speaks.

“I feel quite isolated,” Elliott says. “When it’s breaktime, I normally just watch YouTube in bed.”

Image source, BBC/ Hazel Shearing

Elliott hasn’t been able to play as much football at school as he would have liked

Elliott’s mother, Amanda, says her son had been really looking forward to making new friends. “Not being able to do that in the normal way has really had an impact on him,” she says.

Elliot is due to start in-person learning full-time next week, at an alternative location.

Some year groups have been in the building for a number of weeks, but school life has been far from normal for them too. The children have been learning in a sports hall rather than in classrooms, and using clipboards because there are not enough desks.

Nick Hurn, the chief executive of the school’s trust, hopes all the children will be “back to some face-to-face learning” after half term.

Speaking on a local radio station, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that planning for rebuilding work at St Leonard’s will start before the end of the year.

It is now almost six weeks since the scale of the Raac crisis first emerged.

And despite saying it expected to publish fortnightly updates on the number of affected schools, the government has not released up-to-date figures since last month.

According to the last figures, which were released on 14 September, 174 schools in England were confirmed to have Raac – the material now deemed to be a safety risk, and which has led to the closures.

At 23 of those schools, at least some of the pupils were learning remotely; 29 schools required temporary classrooms -11 already had them in place.

One school – Stepney All Saints Church of England secondary school, in east London, closed completely – meaning all its 1,400 pupils were learning remotely – but has since re-opened to most year groups.

As the impact became apparent, orders were given for 180 single and 68 double classrooms, plus toilet blocks. The DfE has not said how many have been delivered so far.

“The majority of settings where Raac has been confirmed have opened and pupils continue to learn as normal,” a government spokeswoman said.

“We will continue to support all impacted settings in whatever way we can – whether that’s through our team of dedicated caseworkers, or through capital funding to put mitigations in place to minimise the disruption to pupils’ education.”

Image source, BBC/ Hazel Shearing

Tim Hodgson, head teacher at Aylesford School, hopes he will not be faced with Raac, on top of current asbestos and fire-safety concerns

But it is not just Raac that is leading to problems in school infrastructure.

In England, an estimated 700,000 children are being taught in unsafe or ageing school buildings that need major repairs, according to a National Audit Office report from June.

The report said more than 93% of schools had responded to DfE surveys about asbestos. Of those, 80% had identified it.

Asbestos is the reason most of Aylesford School, in Warwick, is closed. It could have Raac – its buildings are the relevant age – but head teacher Tim Hodgson cannot find out for certain until the asbestos is removed.

More than 30 of the school’s classrooms are currently out of use. Classes are using the two remaining science labs on rotation – there are normally eight. Coffee cups and teaching materials are still on desks in padlocked classrooms, left behind by teachers who had to evacuate just days before the start of term.

“We’re educators – we’re not project managers, we’re not builders. So we have to have that help, and we need it quickly,” says Tim.

Aylesford School is on the DfE’s “complex case” list. Around 18 temporary classrooms have been ordered for installation on the netball courts, and are due to arrive in early November.

‘Abandoned’

Siobhan McKenna says her daughter, an Aylesford pupil, feels “overwhelmed” by learning at home.

“I’m a single parent, trying to do a full-time job and keep her on an even keel, and it’s really, really hard not to be able to help,” she says.

Ms McKenna wants Aylesford’s GCSE students to be able to use other schools’ practical teaching facilities, such as science labs.

“What kind of practical lessons can they do in those [temporary buildings]?” she says.

“We just feel completely abandoned.”

Joolz Phillips’ daughter, Scarlett, has been going into Aylesford for a few weeks, but her son, Jacob – in Year 8 – has been at home.

Joolz has been helping other parents who are unable to work from home, by looking after their children too during the day. But that arrangement is now affecting her spray-tan business, which she runs from the family home.

Image source, BBC / Hazel Shearing

Joolz feels lucky that her son has friends to interact with when he’s learning at home

“I had a lovely couple come in for their wedding tans,” Joolz says. “It was a day where it was absolutely chucking it down.

“After I’d done the spray tan, I walked out to trainers and coats all over the floor, soaking wet… What I’ve learnt from that is to try not to do any clients during school hours, if I can.”

Joolz feels that her children have been “forgotten”.

“They’ve had the two years of Covid, they’ve had the teacher strikes’ days… and now we aren’t thought about because nobody else is going through this,” she says.

“Unless you’re living in this right now, you do not understand what is going on.”