What is the mental health public inquiry and what could it change?

Inquest charity

Inquest charity

Mental health patients are among the most vulnerable in society, but services in England have been under huge strain for at least a decade, with sometimes fatal consequences. A public inquiry backed by the government will focus on deaths in Essex as a starting point, but what is it and what does it hope to achieve?

Solicitors representing a growing number of families who have lost loved ones say the Lampard Inquiry, which starts on 9 September, is as important as those around the Post Office and infected blood scandals.

The deaths of up to 2,000 people could be included in it.

Essex has seen repeated failures over 20 years and what has happened in the county could be an indication of what is going on elsewhere. By examining those failures in detail, there could be implications for mental healthcare across the NHS.

The Lampard Inquiry is the first public inquiry specifically looking into mental health deaths.

It will aim to understand what happened to patients who died at children and adult inpatient units, under the care of the NHS in Essex, between the years 2000 and 2023.

The inquiry will focus on Essex Partnership University Foundation NHS Trust (EPUT) and the North East London Foundation Trust (NELFT), along with organisations that existed previously.

It will not look at deaths in the community unless they happened within three months of discharge from a mental health unit, the patient had been assessed and refused a bed, or they were on a waiting list for a bed.

Getty Images

Getty Images

What is an inquiry?

Public inquiries are funded by the government and are led by an independent chair. They can force witnesses to give evidence, although that will not apply to families.

No-one is found guilty or innocent, but the inquiry publishes recommendations. The government can accept or ignore them.

Why is it called the Lampard Inquiry?

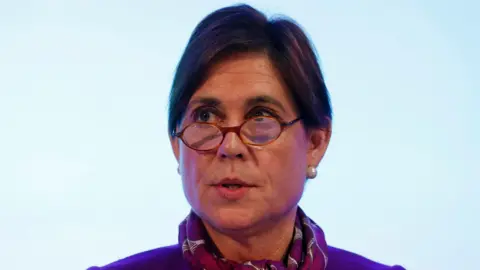

It is named after the chair of the inquiry, Baroness Kate Lampard.

She is a former barrister who oversaw the NHS investigations into abuse by former television presenter Jimmy Savile.

Baroness Lampard is a member of the House of Lords. She is a crossbench peer, meaning she is not affiliated to a party.

She said she wanted to “make recommendations on [how] to improve the provision of mental health inpatient care”.

Why is the focus on Essex?

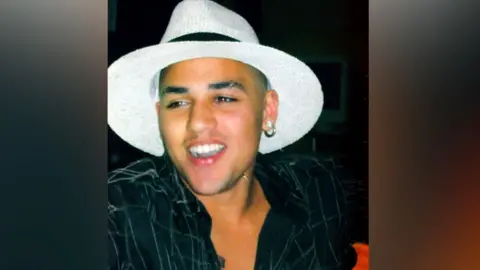

Calls for an inquiry were first made by the mothers of two 20-year-old men who died at the Linden Centre – a mental health unit in Chelmsford.

In 2008, Ben Morris, the son of Lisa Morris, was found dead after calling her to say he wanted to leave.

Four years later, in 2012, staff said they found Melanie Leahy’s son Matthew unresponsive, and he was pronounced dead in hospital. He reported being raped days before he died.

Staff did not follow the trust’s policy following the allegations and his care plan was falsified.

Since then, repeated failures have been raised in the county.

The health watchdog, the Care Quality Commission (CQC), raised concerns around the safety of wards and staffing from 2014 to 2018. Recommendations were not acted on.

In 2017, Essex Police launched a corporate manslaughter investigation into the deaths of 25 patients at nine mental health units, but there were no charges. Police said the cases did not meet the “evidential threshold”.

In 2019, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman published a report into the deaths of Matthew Leahy and Ben Morris. It quoted a “systemic failure to tackle repeated and critical failings over an unacceptable period of time”.

A year later, Melanie Leahy and 24 other families set up an online petition for an independent inquiry. About 105,000 people signed it, forcing a debate in Parliament.

In 2021, former health minister Nadine Dorries said a robust independent inquiry would be held, but it would not have full legal powers to compel staff witnesses to give evidence.

That same year, the Health and Safety Executive fined EPUT £1.5m after the deaths of 11 patients. The judge said there was a “litany of failures” and suicides were not prevented.

Last year, following an undercover report by Channel 4’s Dispatches, the CQC rated two female wards “inadequate”. It showed staff sleeping while they were supposed to be observing patients.

In the same year, the inquiry was given full legal powers at the request of the former chair Dr Geraldine Strathdee, who stepped down for personal reasons.

More deaths were then included for investigation because of “ongoing concerns” over services.

Stuart Woodward/BBC

Stuart Woodward/BBC

What are the concerns being investigated?

Like the Covid inquiry, it will be split into different themes, including:

- Physical and sexual safety in mental health inpatient units, including possible allegations of abuse. The chair said she would use legal powers to ensure evidence is produced, protecting the identity of staff and referring matters to the police, if needed.

- Patient assessments under the mental health act.

- The level of community support.

- Whether wards are safe, fit for purpose and help recovery.

- How patients with different needs like autism or learning disabilities and those with drink and drug issues are dealt with.

- The use of technology like CCTV with sensors and the impact that has on patients’ privacy and dignity.

- How medication is managed and balanced with therapeutic care.

- How patients escape from inpatient secure mental health wards and what happens afterwards.

- The circumstances in which patients are restrained, including the use of seclusion and chemical restraint.

- Whether concerns can be raised by staff.

- Communication with families.

- Staffing, training and the use of temporary or agency staff, and whether there is a connection between poor care and the use of non-permanent staff.

- Culture, management and governance.

- How Essex compares to other places.

Priya Singh, from Hodge Jones and Allen, which is representing 126 families, said: “The deaths of patients in psychiatric institutions cannot continue in the UK.

“This is an enormous opportunity for mental healthcare in England. I’m hoping we can find out what’s been going so badly wrong.”

Mid and South Essex ICB

Mid and South Essex ICB

What do the NHS trusts say?

The current chief executive of EPUT, Paul Scott, said his thoughts were with those who had lost loved ones.

“We will continue to do all we can to support Baroness Lampard and her team to provide the answers that patients, families and carers are seeking,” he said.

However, Mr Scott has disputed the 2,000 deaths figure made public by the inquiry.

He said it included deaths from natural causes, where, for instance, people may have been transferred to hospital after having a heart attack.

NELFT, which provides child and adolescent mental health services in parts of Essex, said: “We will continue to work with the inquiry to help families understand the circumstances surrounding the loss of their loved ones.

“Patient safety is our absolute priority and we are committed to learning from the work of the inquiry.”

How long will the inquiry take?

The inquiry will hear opening statements by chair Baroness Lampard from 9 September.

From 16 September, bereaved families will read impact statements. This will continue during sessions in November.

In 2025, the first evidence sessions take place, with barristers questioning the trusts and other participants on their experiences.

The hearings will take place at the Civic Centre in Chelmsford and be streamed on YouTube.

Ten organisations and 56 relatives, patients and staff will initially give evidence in person, although more may be called to participate as the inquiry progresses.

The inquiry wants anyone who has relevant information or documents to contact them.

The date for a final report is unknown, but it could be a few years.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story, you can get help and support at BBC Action Line.