Germany is developing an app to help people locate the nearest bunker in the event of attack. Sweden is distributing a 32-page pamphlet titled If Crisis or War Comes. Half a million Finns have already downloaded an emergency preparedness guide.

If the prospect of a broader conflict in Europe seems remote for many, some countries at least are taking it seriously – and, in the term used by Germany’s defence minister, Boris Pistorius, taking steps to get populations kriegstüchtig: war-capable.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has dramatically raised security tensions across the Baltic region, prompting Finland and Sweden to abandon decades of nonalignment and join Nato. Military capability, however, is not all: citizens have to be braced too.

“We live in uncertain times. Armed conflicts are currently being waged in our corner of the world. Terrorism, cyber-attacks, and disinformation campaigns are being used to undermine and influence us,” the Swedish pamphlet’s prologue says.

Also available in English, it adds that collective resilience is essential and if Sweden is attacked, “everyone must do their part to defend Sweden’s independence – and our democracy … you are part of Sweden’s overall emergency preparedness”.

Swedes have long been familiar with such public information pamphlets: the first was issued in the second world war. The latest advises on, among other topics, warning systems, air raid shelters, digital security and how to use the toilet if there is no water.

It also recommends keeping a good supply of water at home (and checking annually to see if it is still safe); having plenty of blankets, warm clothes and alternative heating; getting a battery-powered radio; and storing plenty of energy-rich, quick-to-prepare food.

Reaction among Swedish residents has been mixed. Johnny Chamoun, 36, a hairdresser in Solna, near Stockholm, said it was “good to be prepared”. But, he said, while the brochure was a good idea, it had not been much of a talking point.

“In the salon I’ve not heard many people talk about it. Just one said they had got it,” he said. “They’re not stressing or anything.” But Muna Ayan, a healthcare worker from Stockholm, was concerned by how unconcerned many Swedes were.

Having experienced conflict firsthand in Somalia, Ayan said she was frightened. “I am scared because I know what war means – I have survived war,” she said, adding that she had stocked up on water, battery lights, candles and Vaseline.

She was also trying to work out how to tell her five children without scaring them. For people from Somalia, Syria or Iraq, talk of conflict in Sweden was traumatic, she said.

“We who have been in war, we are not well. We are very worried, because if there is war we know what will happen. In war we have lost relatives, some children will disappear.”

And Fatuma Mohamed, a health communicator in Stockholm, said many families in poorer areas did not have food for everyday life, let alone for stockpiling, while others were trying to find out where their local shelters were.

She said she would like to see more information provided to people in person, rather than just in a brochure.

Norway’s directorate for civil protection, DSB, has distributed a similar booklet to the country’s 2.6 million households. “We live in an increasingly turbulent world,” it says, affected by climate change, digital threats and “in the worst case, acts of war”.

The Norwegian pamphlet advises people, for example, to hold at least a week’s worth of non-perishable food including “crispbreads, canned pulses and beans, canned sandwich spreads, energy bars, dried fruit, chocolate, honey, biscuits and nuts”.

Norway also advises residents to stock up on essential medicines – including iodine tablets, in case of a nuclear incident – and, like Sweden, recommends that people have several bank cards and keep a ready supply of cash at home.

In Finland, an exhaustive online guide called Preparing for incidents and crises offers residents information and advice on anything from water outages to wildfires, the collapse of the internet or “longer-term crises … such as military conflict”.

after newsletter promotion

More practically, on a separate website, 72tuntia.fi, Finland – which shares an 830-mile (1,340km) border with Russia – asks its citizens bluntly: “Would you survive 72 hours?” in a range of crisis situations, inviting them to put both their skills and their supplies through a series of tests.

The site has tips on strengthening psychological resilience “to increase your ability to cope in difficult circumstances”, improving personal cybersecurity and sheltering indoors (“Seal doors and windows. Turn on the radio. Wait calmly for instructions.”)

Suvi Aksela of the women’s national emergency preparedness association (Nasta), who is on the 72hours expert committee, said it had considered raising Finland’s food storage recommendation to a full week of supplies, as Sweden and Norway had done.

But in the end, the committee decided against it because the 72hours messaging was so well-established in Finland, she said. “The 72 hours has become a brand here in Finland, so we didn’t want to break that. But that is just the minimum.”

Russia’s war on Ukraine had been a “wake-up call” even in a country that had long been prepared, she said: women had signed up for preparedness courses, battery radios had flown off the shelves, and questions like “how much water do you have at home?” or “do you have a camp stove?” had become “more mainstream”.

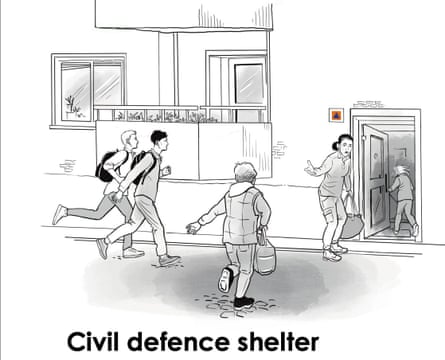

Germany’s focus, meanwhile, is on ramping up the number of its bunkers and protective shelters after an official estimate that the nation of 84 million has fewer than 600 public shelters, together capable of holding just 480,000 people.

Many cold war shelters have been dismantled owing to the belief they would no longer be needed, but Berlin has now launched a national bunker plan under the Federal Office for Population Protection, including a geolocation phone app.

Experts predict an attack by Russia may be a possibility within the next five years and the search is now on for any structure that could be used if such an event occurred, including metro stations and basements of public offices, schools and town halls.

German households have been urged to adapt their own cellars, garages or store rooms, or excavate old bunkers, while housebuilders will be legally obliged to include safe shelters in new homes – as Poland has already done.

The Frankfurter Allgemeiner newspaper this month revealed details of a 1,000-page army document aimed at German businesses – advising them, for example, to train extra lorry drivers – but containing civil preparedness recommendations for individuals.